Measuring Arsenic in Gardens Near a Hazardous Waste Site

Project Overview

After residents of Dewey-Humboldt, Arizona, became concerned about whether arsenic from a nearby Superfund site was contaminating their soil and home gardens, they formed the Gardenroots project with Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta, Ph.D., of the University of Arizona (UA) Superfund Research Program Center (SRP Center). Together they found that the main sources of arsenic exposure were drinking water and incidental soil ingestion. They also learned that arsenic concentrations were higher in home grown vegetables than store brought produce.

Citizen involvement included:

- Collecting garden soil for lab analysis of arsenic content

- Participating in gardening seminars

- Engaging in forums to discuss health concerns

- Informing residents through factsheets and personalized results

Background

Dewey-Humboldt, Arizona, is a rural community adjacent to the Iron King Mine and Humboldt Smelter Superfund (IKMHSS) site. In August 2008, community members expressed concerns about the site’s impact on their soil at a public meeting. Specifically, they wanted to know if it was safe to consume vegetables from their home gardens, and if so, how much they could eat.

In response, Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta, a Ph.D. student and coordinator of the UA SRP Center Research Translation Core at the time, worked together with Dewey-Humboldt residents to investigate the uptake of arsenic in commonly-grown vegetables, and to evaluate arsenic exposure and potential risk to local vegetable gardeners.

Because the research question came from community members who then worked alongside UA scientists throughout most stages of the study, Gardenroots was a co-created citizen science project.

Citizen Involvement

Recruitment for the Gardenroots project was primarily achieved through an announcement in the Dewey-Humboldt town newsletter, through personal interactions at local events, and by community “champions” who initially posed the research question.

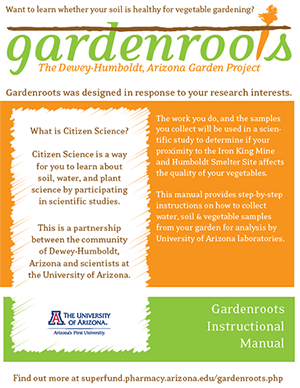

More than 40 community members signed up to attend a 1.5-hour training session on how to properly collect soil, water, and vegetable samples from their home gardens for laboratory analysis. Participants received a home instructional manual and collection toolkit, and were asked to deliver their samples to the local UA Cooperative Extension office.

Ramírez-Andreotta also organized various informal science education experiences. UA Extension personnel and researchers conducted a gardening seminar for beginner vegetable gardeners, and hosted a community health talk to discuss health concerns. Gardenroots participants were also invited on a laboratory tour to see how their samples were prepared for analysis, and what analytical instruments were used.

The study results showed that many of the vegetables that participants were growing in their home gardens had higher arsenic concentrations than those reported in the 2010 U.S. Food and Drug Administration Market Basket Study. Calculations of estimated average arsenic daily intake from the three exposure routes concluded that arsenic exposure was greatest from drinking water, followed by incidental soil ingestion and homegrown vegetable ingestion. The calculation assumes that an individual’s primary source of water for irrigation is also used for drinking.

The presentation and delivery of study findings at a final report-back gathering was instrumental to ensuring that participants understood the data and could use the information to make decisions. Each participant received a personalized booklet containing their household sampling results, including a chart that illustrated how many cups of vegetables per week an individual could safely eat from their garden at different levels of estimated risk. Ramírez-Andreotta led presentations on how to interpret the results, and provided handouts outlining recommended safe gardening practices to help reduce an individual’s arsenic exposure.

Additional presentations on the study and its findings were delivered to Dewey-Humboldt community members and master gardeners in Gila and Yavapai counties. A summary booklet of the study results was also compiled and distributed to study participants and other community members in the Dewey-Humboldt area.

Outcomes

Programmatic outcomes. The Gardenroots project has improved our understanding of 1) the uptake of arsenic in common homegrown vegetables grown in soils near a mining site; 2) the amount of arsenic introduced to an individual through ingestion of homegrown vegetables, incidental ingestion of soil, and water, and the potential risks posed by those exposure routes; and 3) how to implement a co-created citizen science project with a community neighboring a hazardous waste site.

Individual learning outcomes. Surveys indicated that most of the participants understood the scientific findings and would continue to eat homegrown vegetables while modifying their gardening practices to reduce their arsenic exposure from water and soil.

During the report-back gathering, some participants recalculated their potential exposure and risk by changing the exposure assessment variables, such asthe amount or number of days eating a vegetable, to better suit their behavior and way of living. Participants also demonstrated an increased understanding of soil contamination, food quality, and the scientific process by posing additional research questions. For example, they inquired about the quality of chicken eggs, and whether raised-bed building materials like cinder blocks could contribute arsenic to their garden soils.

Community-level outcomes. Gardenroots participants increased their community networking in natural resource-related issues such as soil and water quality, and participated in other natural resource-related projects.

They also leveraged the study results to encourage government officials to take action. The Gardenroots project revealed that water from the local public water system exceeded the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) arsenic drinking water standard, prompting participants to work together to notify other households that were connected to the public water supply. They also reported their test results to federal and state environmental agencies, and as a result the municipal water supplier received a notice of violation for exceeding the EPA arsenic drinking water standard.

Gardenroots also built trust between UA scientists and the Dewey-Humboldt community, setting the groundwork for a long-term community-academic partnership. These efforts also resulted in the initiation of two additional research projects to address remediation and characterization challenges posed by the IKMHSS site. Several Gardenroots participants were hired on as field technicians for a UA biomonitoring study. Ramírez-Andreotta’s work with the local UA Cooperative Extension also helped pave the way for other investigators to partner with the Extension office on their own research projects.

Local, state, and federal decision-makers are using Gardenroots products and study results to inform their work and for use in community outreach materials. Spurred by UA translational science activities in the area, an Iron King transdisciplinary team composed of representatives from the UA SRP Center, federal and state agencies, and the Community Coalition of Dewey-Humboldt has also been formed to coordinate activities, develop public messages, and share information about the community.

New citizen science program launched. Building on the success of the Gardenroots project in Dewey-Humboldt and a recent needs assessment with Extension personnel and rural gardeners, Ramírez-Andreotta launched Gardenroots: A Citizen Science Garden Project in 2015. The project has trained more than 100 citizen scientists to evaluate environmental quality in rural residential and community gardens in Apache, Cochise, and Greenlee counties. More than 50 households have submitted water, soil, plant, and dust samples for analysis.

Challenges

Setting and maintaining expectations. Gardenroots was only able to provide information on potential arsenic exposure from soil, water, and vegetables. It could not generate specific data on health outcomes. For this reason, it was important to reiterate project goals and the types of data that could be expected from the project. Community inquiries regarding potential health outcomes were referred to UA health scientists.

Ensuring participant involvement. The nature of the sample analyses, the formality of the laboratory procedures, and the 3 hour distance between Dewey-Humboldt and the laboratory prevented participants from preparing and analyzing their own samples. To address this issue, Ramírez-Andreotta invited project participants to a UA laboratory tour to learn about the methods used there.

Communication and transparency. Maintaining two-way communication between the Gardenroots project leader and the government agencies working at the IKMHSS site was challenging. Ramírez-Andreotta invited federal and local government stakeholders to participate in the various Gardenroots activities, and set up teleconferences and meetings with the government agencies to help ensure transparency and consistent messaging to the community.

Contact

-

Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor;

Department of Soil, Water, and Environmental Science;

University of Arizona -

Tel 520-621-0091

[email protected]

Related Information

- Gardenroots: Dewey-Humboldt, Arizona, Garden Project Website

- Investigator Update: Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta

- Ramirez-Andreotta MD, Lothrop N, Wilkinson ST, Root R, Artiola JF, Klimecki W, Loh MM. 2015. Analyzing patterns of community interest at a legacy mining waste site to assess and inform environmental health literacy efforts. J Environ Stud Sci; doi:10.1007/s13412-015-0297-x.

- Ramirez-Andreotta MD, Brusseau ML, Artiola JF, Maier RM, Gandolfi AJ. 2014. Building a co-created citizen science program with gardeners neighboring a Superfund site: the Gardenroots case study. Int Public Health J 7(1):139-153.

- Ramirez-Andreotta MD, Brusseau ML, Artiola JF, Maier RM. 2013. A greenhouse and field-based study to determine the accumulation of arsenic in common homegrown vegetables grown in mining-affected soils. Sci Total Enviro 443:299-306.

- Ramirez-Andreotta MD, Brusseau ML, Beamer P, Maier RM. 2013. Home gardening near a mining site in an arsenic-endemic region of Arizona: assessing arsenic exposure dose and risk via ingestion of home garden vegetables, soils, and water. Sci Total Environ 454-455:373-382.