- Jamaji Nwanaji-Enwerem, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.P. – Combining Medicine, Environmental Research, and Policy to Reduce Health Disparities

- Andrij Holian, Ph.D. – Uncovering Mechanisms of Lung Injury to Improve Public Health

- Cynthia Curl, Ph.D., and Carly Hyland, Ph.D. – Teaming Up to Protect Agricultural Communities in Idaho

- Yoshira ‘Yoshi’ Ornelas Van Horne, Ph.D. – Putting Communities at the Center of Exposure Science Research

- Molly Kile, Sc.D. – Conducting Community Participatory Research Across Continents

- Karletta Chief, Ph.D. – Partnering with Tribal Communities to Protect Water from Pollution and Weather-Related Hazards

- Kathleen Gray, Ph.D. – Improving Environmental Risk Communication Through Interdisciplinary Collaborations

- Gary Adamkiewicz, Ph.D. – Using Housing as an Opportunity to Improve Health

- Celia Chen, M.S., Ph.D. – Leveraging Partners Across Disciplines and Continents

- Jennifer Carrera, Ph.D. – Joining Forces With Communities to Bridge Gaps in Public Health

Jamaji Nwanaji-Enwerem, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.P. – Combining Medicine, Environmental Research, and Policy to Reduce Health Disparities

November 16, 2022

From a very early age, Jamaji Nwanaji-Enwerem, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.P., a former NIEHS-funded postdoctoral fellow, knew he wanted to pursue a career addressing health disparities in the U.S. and abroad. A Nigerian-American, Nwanaji-Enwerem recalls traveling back and forth between the two countries and observing how populations in both nations experience similar health disparities, such as lack of access to healthcare.

“Seeing how health disparities impact people’s lives and their ability to provide for their families sparked my interest in a career that merges both medicine and research,” said Nwanaji-Enwerem, who earned his M.D., Ph.D., and a master’s in public policy from Harvard University. “When I went off to medical school, I was resolute in doing research that was translational in nature, meaning that its findings can have more immediate and lasting contributions, so that fewer people have to experience illnesses related to environmental exposures in the places where they live and work.”

Nwanaji-Enwerem completed his postdoctoral training at the University of California, Berkeley under the guidance of Andres Cardenas, Ph.D. An expert in the field on environmental molecular epidemiology, Nwanaji-Enwerem is now an emergency medicine resident doctor at Emory University’s School of Medicine and an adjunct assistant professor at the School of Public Health.

Predicting Risk of Disease

At the Cardenas lab, Nwanaji-Enwerem’s research aimed to understand how environmental exposures can speed up or slow down biological aging, one of the risk factors for many human diseases, for populations such as children.

“Our chronological age, based on when we were born, and biological age are often not the same. Damage to our cells, from environmental toxins and many lifestyle factors such as diet and sleeping habits, can impact a person’s biological age,” Nwanaji-Enwerem said.

“We hope to use biological aging as a biomarker, or measure, to predict someone’s risk for a disease before they become critically ill,” he continued. “By understanding how exposures impact aging, we can intervene to mitigate adverse aging effects before they lead to illness.”

Community-inspired Projects

At Emory, Nwanaji-Enwerem splits his time between teaching, research, and seeing adult and pediatric patients in the emergency room.

“After people are admitted to the hospital or discharged home, I often find myself reflecting on our interactions. What larger social and environmental factors contributed or exacerbated their disease processes? Are there larger systemic issues related to their problem that still have not been addressed?” he reflected. “These experiences are the inspiration for many of my environmental health research projects and community-based efforts that I pursue in my roles as an adjunct assistant professor and concerned global citizen.”

In 2021, Nwanaji-Enwerem launched ELND, an initiative to help connect, promote, and fund community-level projects. One of their projects, the Vibrations: African Environment Photo Essay Contest provided an opportunity for individuals living in Africa to share their environmental improvement and education efforts and the impacts they are making on their communities.

“The photo essay contest allowed me the privilege of meeting a number of leaders who are making phenomenal impacts in their communities,” Nwanaji-Enwerem said. “Projects included efforts to plant shrubs and trees to fight deforestation, recycling initiatives to manage solid waste, and community residents educating their neighbors about the environmental risks they face every day.”

The contest allowed community leaders to spread awareness about their work and receive funding to continue that work.

“We need as many hands as we can get to solve the problems our world is facing,” Nwanaji-Enwerem shared.

Andrij Holian, Ph.D. – Uncovering Mechanisms of Lung Injury to Improve Public Health

October 18, 2022

A proud Ukrainian American, Andrij Holian, Ph.D., recalls deciding to become a scientist in fifth grade. His significant contributions to the field of environmental health can be attributed to his unending curiosity and determination to always ask, “Why?”.

After receiving his Ph.D. in Chemistry from Montana State University in 1975, Holian joined the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. There, his experiences sparked an interest in understanding the role of macrophages — immune system cells that help eliminate foreign substances and protect the body from infection — in lung injury.

Holian later moved to the University of Texas Houston Health Science Center, where he became Director of Research for the Mickey Leland National Urban Air Toxics Research Center.

“At the University of Texas, I had the opportunity to start connecting my interests in lung disease research, exposure assessment, and training new scientists,” Holian said. “I developed an NIEHS-funded toxicology training program in collaboration with Texas Southern University, which was among the first programs of its kind to combine the strengths of a research-intensive and Historically Black University.”

Pathways of Lung Damage from Particle Exposure

In 2000, Holian established a Center for Environmental Health Sciences (CEHS) at the University of Montana following national concern about mining operations that exposed the Libby, Montana community to toxic asbestos compounds. Since then, Holian has received several NIEHS grants to investigate how inhaling different harmful particles can cause inflammation and damage the lungs.

“Many human diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, asthma, and cancer, can be tied to inflammation,” Holian explained. “Understanding the mechanisms behind inflammation will allow us to develop therapeutics with significant benefits for human health.”

Holian’s research focuses on health effects from exposures to engineered nanomaterials (used in a variety of industrial and commercial applications) and silica (used to make glass, stoneware, and granite countertops). In the U.S., millions of workers are exposed to silica dust, which may increase their risk of developing chronic lung diseases.

Holian was among the first researchers to demonstrate the connection between silica-induced lung injury and macrophages. While macrophages in the lungs play a key role in keeping the lung surface clean and preventing particles from accumulating, they may be susceptible to damage from silica exposure.

“First, macrophages engulf silica particles as part of the cleaning process,” Holian said. “The particle then enters the cell’s lysosome, or the ‘stomach’ of the cell whose job is to break down waste, but the lysosome cannot digest silica.”

According to Holian, silica can disrupt the lysosome’s membrane, injuring the cell and initiating inflammation. The freed silica particle may then be engulfed by another macrophage, continuing the cycle of lung damage.

Long-term exposure to silica particles, and the resulting cell injury, can result in silicosis, a lung disease caused by the buildup of scar tissue that currently has no cure. Holian hopes that by studying mechanisms of lung damage, he can mitigate the risks associated with particle exposures.

“All of these discoveries have been co-dependent on the work of my students,” Holian added. “I may not be able to personally develop a treatment for lung damage and disease, but the students I train might.”

Shaping Science at All Levels

In addition to making scientific discoveries, Holian considers his connection with students another of his greatest rewards. From elementary school students to post-doctoral researchers, he is devoted to training the next generation of scientists.

“I’m developing educational materials and graphic novels for elementary and middle school students to keep them engaged in science,” Holian said. “This is a defining point in their lives — it is important for them to maintain their curiosity.”

Holian also mentors college students by leading the University of Montana’s CEHS Summer Undergraduate Research Program, which provides students from around the country an authentic immersive experience in conducting environmental health sciences research.

Through the program, students gain critical research skills, as well as confidence and guidance to pursue graduate education.

“Our program introduces students to how critical a team approach is to solving problems,” Holian said. “I want to continue to be a strong advocate for training, education, and discovering the next important environmental health issue to address.”

Cynthia Curl, Ph.D., and Carly Hyland, Ph.D. – Teaming Up to Protect Agricultural Communities in Idaho

September 19, 2022

Growing up on a farm in rural Virginia, Cynthia Curl, Ph.D., was fascinated by the connection between food systems and their role in communities. That early interest led to her role as an associate professor of public and population health at Boise State University, where she studies the effects of agricultural practices on health.

“Being part of an agricultural community is something that gives people a sense of pride — it provides jobs and it's important in terms of feeding us all," Curl explained. "But there are also health risks involved. I am passionate about understanding the effects of working and living in agricultural communities and how food production systems affect human health.”

Today, as head of the Curl Agricultural Health Research Lab at Boise State, she is on a mission to protect agricultural communities from chemicals used in food production.

Growing Agricultural Health Research in Idaho

Although Idaho has a large agricultural community, it hasn't historically received the same amount of research funding as other agricultural states, like Washington, Oregon, and California, according to Curl.

"We didn't have a group already doing this work," she explained. "NIEHS support has played a big role in allowing me to create a new path and start building an agricultural health research hub in Idaho."

According to Curl, building the research hub hinged on finding the right team for the job. That’s where post-doctoral researcher Carly Hyland, Ph.D., came in.

Curl, right, talks with a community member in a local market.

(Photo courtesy of Cynthia Curl)

Hyland recently completed her doctorate in environmental health science and was a part of the NIEHS-funded Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS) research team, which examines the effects of pesticides and other environmental exposures on children’s health over time in the agricultural region of Salinas Valley, California.

“I came to Boise State because there's a need for this type of work in Idaho, but also because I wanted to work with Dr. Curl," said Hyland. "Her expertise in exposure assessment along with our common goal of translating research findings to protect communities made our partnership ideal."

Hyland is currently researching pesticide exposure and risk perceptions among male and female Hispanic farm workers.

“Most previous studies have looked almost exclusively at male farm workers because they are still the larger proportion of the workforce,” Hyland explained. “But women are making up an increasing proportion, so we are comparing pesticide exposure and also looking at factors that might uniquely affect their exposure, such as improperly fitting protective equipment, which is often made for men.”

Research Rooted in Community

The Curl Agricultural Health Research Lab. From left to right: Hyland, Alejandra Hernandez, Elysia Watkins, Annica Balentine, Curl, Meredith Spivak, Carson Schvaneveldt, Brie Ellison.

(Photo courtesy of Cynthia Curl)

Partnerships with Women, Infants, & Children (WIC) clinics, the Idaho State Department of Agriculture, the Idaho Organization of Resource Councils, nonprofit organizations, and advocacy groups were key starting points for recruitment and relationship-building.

“In applying to grants, we include community groups as funded partners,” Hyland explained. “This ensures our results are disseminated to agricultural communities by trusted entities.”

This connection also opens the door for Curl and Hyland to present their findings to local communities and provide concrete recommendations on how to reduce pesticide exposure.

“What I have heard from all our community partners is that they're incredibly grateful for this research because there's a huge need for it in Idaho,” Hyland explained. “They are engaged and excited about working with us hopefully for a long time to come.”

Yoshira ‘Yoshi’ Ornelas Van Horne, Ph.D. – Putting Communities at the Center of Exposure Science Research

August 23, 2022

Every data point is a person, and every person deserves respect and answers. That philosophy guides Yoshira "Yoshi" Ornelas Van Horne, Ph.D., who studies what chemicals people are exposed to in the environment and how those exposures occur. She says the field of exposure science has not always taken a community-centered approach to research – and she wants to change that.

“To fully characterize people’s exposures, you have to work with and listen to communities to understand their stories and lived experiences,” said Ornelas Van Horne, an assistant professor at Columbia University.

It was through her graduate and postdoctoral research on two NIEHS-funded projects – one working with Diné (Navajo) communities, the other with Latino children and their families – that she came to recognize the importance of including community perspectives in exposure science research.

Water Is Life

Ornelas Van Horne first saw the benefits of a community-based approach during her doctoral research at the University of Arizona. With her advisors, Paloma Beamer, Ph.D., and Karletta Chief, Ph.D., she worked on an NIEHS-funded project to understand exposure risks for Diné communities following the 2015 Gold King Mine spill, which sent 3 million gallons of polluted water into the San Juan River.

“For the Diné, water is life,” she explained. “The river supports their livelihood and is essential for many cultural and spiritual activities.”

The spill demanded a risk assessment, an evaluation of how the polluted water may harm human health and the environment. However, that assessment was based on the needs of outdoor recreationalists and did not consider how Diné communities interact with the river and how those interactions can affect health, according to Ornelas Van Horne.

To help address Indigenous community health concerns, Ornelas Van Horne collaborated with Diné students, researchers, and community health representatives.

Through focus groups and surveys designed with community members, the team identified 43 distinct ways in which the Diné rely on the San Juan River for their livelihood, diet, recreational, cultural, spiritual, and arts and crafts activities.

“Excluding these activities from the risk assessment process can result an underestimation of exposures for the Diné people,” she said.

Ornelas Van Horne and her Diné research partners shared their results through culturally appropriate materials. Their approach included:

- Creating print materials that were individually delivered to participants.

- A series of videos narrated in Navajo.

- Hosting meetings in Navajo Chapter houses, a familiar and important space for participants.

- Ensuring a Diné translator was present at all meetings.

- Respecting Indigenous data sovereignty, or the right of the Diné to govern how study data is collected, who owns it, and how it can be used.

Importantly, the research team disseminated Diné-specific water use guidelines for crop irrigation and livestock purposes — two of the main ways participants reported interacting with the river. The guidelines help Diné communities make informed decisions about river-based farming practices and allow them to continue passing cultural farming traditions down to younger generations.

The Reason Behind the Research

Ornelas Van Horne said that working with the Diné community was one of the biggest “aha!” moments of her career.

“I just knew that this was it, that this is how we move science forward — by partnering with communities to answer their questions. From that point on, I knew I only wanted to do research if it involved and benefited communities,” she said.

That revelation spurred her to take a postdoctoral position at the University of Southern California where she worked with Latino families in the agricultural community of Imperial Valley, California. Supported by an administrative supplement from NIEHS, she aimed to address community concerns about pesticide exposure and children’s respiratory health.

“Many schools and homes in Imperial Valley are located near agricultural fields sprayed with pesticides. Parents are worried that exposure to these pesticides may contribute to asthma in their children,” said Ornelas Van Horne, who noted that the area has some of the highest child asthma rates in the state and nationally.

To shed light on this association, she is using data from the NIEHS-funded Assessing Imperial Valley Respiratory Health and the Environment (AIRE) study. Co-led by Shohreh Farzan, Ph.D., and Jill Johnston, Ph.D., AIRE researchers are assessing how dust from the drying Salton Sea, pesticides, and other air pollutants affect respiratory health in more than 500 elementary school-age children.

“None of this would be possible without our community partner, Comité Cívico Del Valle, and the Imperial Valley families and children, who are so willing to participate in the AIRE study in hopes of a healthier community,” she said.

Her research is ongoing, but preliminary findings suggest a link between pesticide applications, especially sulfur, and an increased risk of wheezing in children.

Roadmap for Redefining Exposure Science

To help other exposure scientists take a community-centered approach, Ornelas Van Horne and collaborators developed a framework. The framework encourages researchers to move beyond simply characterizing harmful exposures to identifying and implementing solutions for communities — especially those dealing with high levels of pollution.

For those scientists, Ornelas Van Horne offers this advice: “Let go of your assumptions and take time to listen. You can learn a lot from community members and that local knowledge will help strengthen your science and generate community-driven solutions.”

Molly Kile, Sc.D. – Conducting Community Participatory Research Across Continents

July 22, 2022

Molly Kile, Sc.D., resolutely uncovers threats to populations most vulnerable from environmental exposures, including children and families living in areas with limited resources.

An environmental epidemiologist at Oregon State University (OSU), Kile works with communities in rural, low-resource, and primarily minority regions in the U.S. and abroad to understand and address their needs.

Kile’s passion for protecting children’s environmental health grew out of her doctoral training at the Harvard University NIEHS-funded Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center. She was mentored by David Christiani, M.D., who was studying arsenic exposure in Bangladesh.

“My work with Dr. Christiani allowed me to travel to Bangladesh and live with a community for a month. Through conversations with families, I learned that their primary concern was understanding how contaminants affect the health of their children and how to protect them,” Kile reflected. “That trip was an epiphany that helped shape the research I am conducting today.”

Arsenic Research in Bangladesh

Early in her career, Kile received a Mentored Research Scientist Development Award grant from NIEHS. The award allowed her to combine formal education with mentorship and training to start addressing the health concerns she heard about in Bangladesh, such as how arsenic exposure during pregnancy affects the health of a mother and her baby.

Kile’s work in Bangladesh provided insight that linked arsenic exposure during pregnancy to low birth weight and disruptions to the developing immune system.

Building on those research findings, Kile, colleagues at Harvard, and community partners in Bangladesh developed prenatal health care and well-baby care at Dhaka Community Hospital Trust and their rural health clinics. Their work also informed new Bangladeshi policies for safe drinking water options in communities impacted by arsenic contamination.

“One of the key lessons I learned is that partnering with a local organization that residents trust and that can explain the value of research is critical,” Kile reflected. “Those partnerships help us build trust within the community and hold us accountable to make sure our work benefits residents.”

Serving Native American Communities

Kile applies the lessons she learned working with communities in Bangladesh to her role leading the Community Engagement Core at the OSU SRP Center. Her team partners with Native American tribes in the Pacific Northwest to address their concerns about environmental pollutants, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

For example, Kile and team have partnered with trusted leaders within tribal communities to facilitate bidirectional research. The collaborators help tribal members understand the health threats from PAH exposure and develop culturally appropriate strategies to protect their health.

“When working with Native American communities, you have to be respectful of their sovereignty and their right to decide how environmental samples and information will be collected, analyzed, used, and shared with outsiders,” Kile said. “A big component of our work is teaching university-based researchers how to conduct and communicate research in a way that respects Tribal Nations and nurtures current and future relationships.”

Translating Research into Action

Kile also co-leads OSU’s NIEHS-funded Advancing Science, Practice, Programming and Policy in Research Translation for Children's Environment Health (ASP3IRE) Center. The center aims to translate findings from children’s environmental research into interventions that can reduce children’s exposure to pollutants and improve their health and well-being.

“We’re trying to accelerate the uptake of policies, programs, and practices that will mitigate environmental exposures before they can harm children’s health,” said Kile. “The ASP3IRE Center is a wonderful collaboration between researchers from different disciplines who all share a common goal of improving children’s health and well-being.”

The team is committed to working with local organizations that support children and families. For example, they launched a pilot project program for community-based organizations, healthcare providers, and learning centers, among others to propose and test interventions that can improve children’s environmental health.

“A lot of environmental exposures, especially in a person’s home, are controllable,” Kile reflected. “I hope that by providing communities with the right support, education, and resources, we can empower them to make and inform changes to protect their health and well-being.”

Karletta Chief, Ph.D. – Partnering with Tribal Communities to Protect Water from Pollution and Weather-Related Hazards

May 24, 2022

(Photo courtesy of Karletta Chief)

Karletta Chief, Ph.D., a hydrologist at the University of Arizona, facilitates collaborations between Indigenous communities and researchers to build resilience and improve environmental health.

Chief explained how her interest in water stemmed from growing up within Navajo nation.

“Water is a real part of my identity,” Chief explained in a Science Friday video series. “The Navajo people, or Diné people, have this deep connection to the environment.”

Despite the importance of the environment to their livelihood and culture, Chief’s community lives where their environment is threatened by mining operations.

“Coal mining pollution affected my family both environmentally and health wise, and that is what fueled my motivation to study water and help my community understand how to better protect themselves.”

After receiving her Ph.D. in Hydrology and Water Resources from the University of Arizona, Chief completed her postdoctoral research at the Desert Research Institute, where she began to explore how extreme weather can further affect tribal communities’ water.

Today, as the Community Engagement Core (CEC) lead for the NIEHS-funded Superfund Research Program Center and the Director of the Indigenous Resilience Center, Chief is working to understand and address impacts on tribal water sources from both environmental contamination and Weather-Related Hazards.

Addressing Community Needs

In response to the Gold King Mine Spill in a local water supply, Chief led a team that conducted a rapid response assessment to the disaster based on community questions and concerns.

The research team identified exposure pathways unique to tribal communities living near the river. In addition to recreational and agricultural uses – often considered in traditional research studies – they documented the community’s spiritual, cultural, and artistic connections to the river.

“We gathered data on over 40 different activities where Native Americans engaged with the river that traditionally had not been considered in research projects, she said. “This data showed that we have to understand the community and look beyond what is conventional to truly characterize environmental health.”

An important part of their work included reporting research findings back to the community. Chief, who typically makes presentations to residents in the Navajo language, and her team translate the scientific findings into information relevant to the farmers, ranchers, and families who are affected.

“Addressing tribal challenges has to include the communities’ perspectives, knowledge, and aspirations in order to truly have the greatest impact,” said Chief. “We are visitors to these communities, but they will have these challenges for the long term.”

Building on this project, Chief and team continue to better understand health inequities in Native American communities. She partners with multiple tribal nations to build their capacity to mitigate environmental health risk within a holistic Indigenous framework that includes language, culture, education, health, and the environment.

Focus on Resilience

Chief explained how the Indigenous Resilience Center grew out of the work and collaborations surrounding the Gold King Mine project.

The center, which focuses on agriculture, solar energy, off-grid water resources, food resources, and Native plant adaptation, among others, is striving to curate a hub of individuals doing similar work supporting resilience of Indigenous communities.

“It is critical that Native nations drive the research questions based on their priorities and long-standing local knowledge, and that the approaches involve decolonized and Indigenized approaches with Indigenous scientists leading these efforts,” she said. “Building this team will allow us to branch out to make an impact with more communities and build resilience in a way that is respectful of traditional knowledge, acknowledges tribal sovereignty, and aims to be transparent,” she said.

Celebrating Contributions

Recently, Chief received the University of Arizona Distinguished Outreach Faculty Award for 2021. Chief will be honored with a bench featuring quotes chosen by her to be placed within the new Women's Plaza of Honor. The plaza is to recognize the role of women in academia and the university.

“I was really touched by this honor because I come from a community where women are the leaders and givers of our identity, culture, and language, but that is not common in academic spaces,” she explained. “The bench in the plaza will bring my two worlds together.”

Chief explained that she is proud to stand on the shoulders of the many women who laid the foundation and sacrificed for women’s rights. She looks forward to her bench becoming a building block of inspiration for others to go on and do positive things in the world.

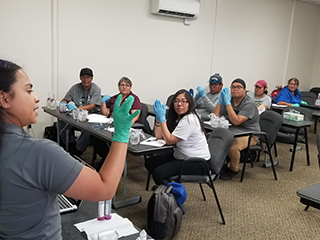

Kathleen Gray, Ph.D. – Improving Environmental Risk Communication Through Interdisciplinary Collaborations

May 6, 2022

(Photo courtesy of Kathleen Gray)

Kathleen Gray, Ph.D., of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill (UNC) has long held a passion for increasing understanding of environmental exposures in communities affected by contamination.

After completing her undergraduate degree, she worked with community-based organizations in southern Louisiana that were responding to contamination from nearby chemical and petroleum industries. Gray was part of a team that collected and analyzed water and soil to understand the extent of exposure. While working alongside community leaders to share results in public meetings, Gray discovered a passion for communicating about environmental health risk and facilitating dialogue on how to respond.

“My work in Louisiana was a springboard into risk communication and stakeholder engagement,” says Gray. “Now, after decades of working in North Carolina communities, and with academic training in science education, I find myself being called on to advise environmental science colleagues about how to communicate the implications of their research findings to community members.”

Today, Gray leads the Community Engagement Cores at the NIEHS-funded Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center and Center for Environmental Health and Susceptibility (CEHS) at UNC, where she continues innovating environmental health risk communication for diverse communities.

“The UNC SRP brings biomedical, environmental, and social scientists together to conduct research that addresses complex environmental challenges related to toxic metals in drinking water and fish, while the CEHS focuses on asthma, lead and healthy homes, and environmental cancers,” she explains. “These are important issues for our communities in North Carolina.”

Together these teams develop outreach and educational materials to help communities better understand how the environment can affect their health. Community resources include mapping tools, infographics, and educational activities.

“Scientists may not have experienced living in a community where their health is threatened by the environment, so empathy is very important,” Gray says. “Engaging communities and key stakeholders throughout the research process ensures our research is relevant while improving scientific understanding and communications about these difficult issues.”

Broadening Understanding of Environmental Concerns for Maternal and Child Health

One of the groups Gray works with is the fishing community in North Carolina. Lakes in the area may contain contaminants that end up in the fish people eat, which can be especially concerning for women of childbearing age and children because they can cross the placenta and contaminate breast milk which can affect brain and other development.

In one study, Gray and colleagues assessed how well fish consumption advisory signs alerted anglers to these contaminants in the Badin Lake area using focus groups with English- and Spanish-speaking anglers.

“We found that while men were not the most at risk, they were sharing fish with the most at-risk groups,” Gray explains. “If we had not asked them about both their perceptions and their habits, we would have missed that they were giving fish to women and children in the community. Asking the anglers about their children, grandchildren, and other family members they shared fish with helped them realize the personal relevance of the advisories.”

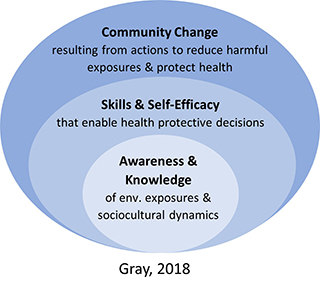

Expanding the Definition of Environmental Health Literacy

Gray’s work with anglers exemplifies a core tenet of the expanded understanding of environmental health literacy (EHL) she and others are establishing: a version that includes collective action and community change.

(Figure from Kathleen Gray, Ph.D., 2018)

As an emerging framework, EHL is often described as an individual’s ability to connect environmental exposures to their health. Gray sees value in taking a broader view by expanding this idea to include community change as a dimension of EHL and exploring ways to measure it in her work.

“Focusing on one person’s knowledge and decisions could help that one person, but if that’s the only lens we have, we miss opportunities to make widespread change,” reflects Gray. “Looking across a community opens us up to making changes that have far-reaching benefits. That’s why I’m committed to broadening our understanding of EHL and thinking creatively about how to measure it.”

Gray and collaborators developed and tested an EHL tool to evaluate people’s understanding of toxic metals in well water. They explored how EHL depends on context and examined participants’ beliefs about with EHL.

“Early EHL measurement tools tended to focus on a person’s knowledge. For example, whether they could connect an exposure to a health outcome after being given some information,” Gray explains. “But if we know more about their health beliefs and the local community dynamics, we can better understand what might influence them to take action toward safer, healthier environments.”

Teaching and Learning from the Next Generation

Gray and her SRP colleagues enjoy working alongside North Carolinians of all ages, especially young people. With UNC SRP team member Sarah Yelton, M.S., Gray is leading two National Science Foundation-funded projects to engage youth in STEM to develop local solutions for environmental impacts in their communities. Insights from other SRP teams have led to new approaches to this work.

“The value of SRP is being able to learn from a network that has experience with projects like ours,” she explains. “In our program, Sarah, our colleague Andrew George, Ph.D., and I have been in active conversation with colleagues in the Dartmouth SRP Center to learn how they used citizen science approaches with high school classes to monitor local well water quality. Harnessing the SRP network to create programs that are meaningful and personalized for our youth motivates them to take action in their communities.”

Gray and colleagues Ilona Jaspers, Ph.D., who leads the UNC SRP Research Experience and Training Coordination Core, and Antonio Baines, Ph.D., an associate professor at North Carolina Central University, collaborated to create research experiences in environmental health sciences for students in STEM through the NIEHS-funded 21st Century Environmental Health Scholars.

The year-long program gives students a chance to conduct research in a supportive lab setting and creates pathways them to enter this field. According to Gray, the only way to solve the environmental health problems is to build teams are that include a range of perspectives and scientific disciplines.

Gary Adamkiewicz, Ph.D. – Using Housing as an Opportunity to Improve Health

April 18, 2022

Gary Adamkiewicz, Ph.D., is bringing the conversation about healthy environments indoors. An associate professor of environmental health at Harvard University, Adamkiewicz works to understand – and control – sources of air pollution in the home, with a focus on low-income communities and public housing developments.

“We know that 90% of our time is spent indoors, and a big fraction of that is spent at home,” he explained. “So why not start there when trying to create better environments?”

As a proud first-generation college student, Adamkiewicz started out studying chemical engineering, later earning a Ph.D. in the field from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While conducting his doctoral research on developing air pollution control strategies, he became interested in asthma. But it was when he connected with Jack Spengler, Ph.D., at Harvard University that everything clicked.

“He [Spengler] was examining factors in public housing that were linked to asthma, and that work really brought together a lot of my research interests – asthma risk factors, working with vulnerable populations, and taking a solutions-oriented research approach,” he said.

Now, Adamkiewicz sees housing as an opportunity to improve health. Through his work with two NIEHS-funded centers at Harvard, he partners with community groups to reduce housing-related exposures in the city.

The Indoor Neighborhood

There's a long list of exposures within the home that contribute to poor air quality and health, including gas stoves that emit nitrogen dioxide, allergens related to pest problems, and chemicals that are released from personal care products and building materials. On top of that, housing attributes, like home size and ventilation, and resident activities, like cooking practices and personal care product use, also influence indoor air quality.

“In our research we consider all these factors to get a complete picture of how an individual’s housing may shape their health – and then we work to reduce those exposures,” said Adamkiewicz.

With support from the Center for Research on Environmental and Social Stressors in Housing Across the Life Course (CRESSH), Adamkiewicz and team set out to better understand the factors driving levels of fine particulate matter air pollution (PM2.5) in Chelsea, Massachusetts homes. He teamed up with partners at the Boston University School of Public Health and the organization GreenRoots to recruit study participants and placed real-time air monitors in residents’ homes. They also conducted a home visual assessment and collected information on activities in the home.

“It’s a leap of faith to allow a researcher you don’t know into your home. But we were extended trust because of our partnership with GreenRoots,” he said.

They found that families who rented and lived multifamily buildings had significantly higher levels of PM2.5 compared to homeowners. The researchers attributed this to resident activities and building-level factors, like cooking, smoking, and building size.

“What your neighbor is doing matters. If your neighbor is cooking, those pollutants are probably finding their way into your unit,” said Adamkiewicz. “People talk a lot about neighborhood effects, but there is also an ‘indoor neighborhood’ we need to consider.”

Through individual exposure reports and a community meeting, the research team returned study results to participants and provided them with actions to improve indoor air quality, such as opening windows or using exhaust fans to eliminate indoor pollutants.

“Our goals were to teach study participants about sources of indoor air pollution and empower them to take action on air quality issues at home and in their community.”

People, Places, Policies

For Adamkiewicz, moving his research to action is all about the three P’s – people, places, and policies.

For the people piece, he explained that it’s critical to educate residents so that they have the tools and resources necessary to create and maintain a healthy living space.

Places is all about building healthier buildings and making sure they operate and are maintained correctly.

Policies at the local level – such as smoke free housing and better pest control – can help create healthy spaces and keep them healthy for the long term. This is especially important in public and multifamily housing.

For students who want to make sure their research has an impact, Adamkiewicz offered this advice: get involved at the grassroots level, partner with community groups, and work with academics who are doing action-oriented research.

Celia Chen, M.S., Ph.D. – Leveraging Partners Across Disciplines and Continents

February 18, 2022

Internationally recognized researcher and long-time NIEHS grantee Celia Chen, Ph.D., Dartmouth College, studies how pollutants accumulate in freshwater and marine food webs where they can pose a threat to human health.

“I grew up in a very industrialized area in New Jersey,” Chen explained. “I remember noticing the pollution as a child and being interested in understanding it better. Later, things really came full circle when I ended up doing research at the very Superfund site my family drove by regularly to go shopping.”

Today, Chen co-leads a project collaborating with the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services and Clarkson University to assess the presence of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in fish and shellfish in the Gulf of Maine. By integrating this data with information on local seafood eating habits, the team aims to inform health protective policies for PFAS.

According to Chen, this project builds on nearly three decades of research through the NIEHS-funded Dartmouth College Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center.

"What I love about science is that it is this series of connections and collaborations with diverse groups that open up new questions and opportunities to address them," she explained. “Having the right team was critical to being able to quickly pivot to address emerging questions. We’ve leveraged our work on mercury as part of the Dartmouth SRP Center to start thinking conceptually about PFAS, because the questions surrounding PFAS now are very similar to questions we had about mercury many years ago.”

Scaling Research from Local to Global

Through the center’s community engagement and research translation activities, Chen’s research on mercury connects varied groups worldwide, from high school students, to communities, and governmental decision makers.

For example, she described the Dragonfly Mercury Project, which began as a high school curriculum and grew into a successful national initiative.

“My collaborator at the University of Maine started the project over 10 years ago to teach high schoolers about how mercury moves and changes in the environment,” Chen said. “The Dartmouth SRP Center took it on and expanded it in schools in New Hampshire and Vermont. Now it has been adapted into a project led by the National Parks Service and the U.S. Geological Survey.”

Analyzing samples collected by community scientists, including by high school students in New England, demonstrated that dragonflies can be used as a simple and effective indicator of mercury contamination in fish and other wildlife.

Chen explained that this local data on mercury can inform the larger picture.

“Mercury can be a local problem where there are coal fired plants or small gold mines, but it can be transported around the world in the atmosphere as far as the Arctic,” said Chen. “Mercury and other persistent organic pollutants require that global partnerships come up with solutions that everyone can agree on.”

Working with collaborators across the globe, Chen helped produce four papers for a special issue of the journal, Ambio. Their goal was to describe the latest research on mercury, laying the foundation for how this science can help inform environmental policy, particularly activities under the Minamata Convention, a global treaty on mercury that was ratified in 2017. Chen and collaborators are repeating this exercise through an NIEHS-funded workshop to develop another series of papers to inform future discussions surrounding the treaty.

Understanding Exposures

Chen and team are also clarifying how environmental changes associated with climate may affect mercury exposure for humans. For example, they reported that when water temperatures rise, fish eat more and absorb higher levels of mercury.

“Findings on mercury show that with warming waters, humans may be exposed to higher levels of metals from eating fish,” she said.

Based on those experimental and field studies, Chen and team will next explore how factors like organic carbon, affected by changes in precipitation patterns , may alter how PFAS move in the food web.

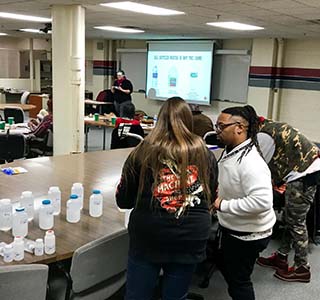

Jennifer Carrera, Ph.D. – Joining Forces With Communities to Bridge Gaps in Public Health

January 24, 2022

At Michigan State University, Carrera integrates sociology and engineering to identify practical solutions to address community environmental health concerns. (Photo courtesy of Jennifer Carrera)

NIEHS grantee Jennifer Carrera, Ph.D., works with communities experiencing environmental challenges surrounding inadequate water and sanitation systems to understand and address health risks.

While earning her master’s degree in sociology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Carrera became aware of the lack of resources in some communities to properly manage their waste.

While working towards her Ph.D. in sociology, Carrera realized she would need a different skill set to find solutions to community water and sanitation challenges. That’s when she began to study engineering.

Finding Solutions to Sanitation Issues

Carrera shared how some existing engineering solutions for water issues were too expensive for the communities who needed them. Others, such as the low-cost latrines used in international communities, she explained, are inappropriate for communities in the United States. There is a cultural expectation of indoor plumbing.

“Sociology offers an understanding of why problems exist, but not how to solve them, whereas engineering provides solutions to problems without understanding the root causes of why they exist,” she explained. “I decided to focus on building a bridge between these two areas to think about problems and solutions with a multi-dimensional view to create new solutions.”

Since starting as an assistant professor at Michigan State University, Carrera has focused her research on developing low-cost technologies to address the water quality and access problems that local communities struggle with. She was awarded a NIEHS-funded Transition to Independent Environmental Health Research (TIEHR) Career Award to pursue this work in Flint, Michigan.

Centering Community Perspectives in Research

The heart of Carrera’s work is supporting communities’ goals to access the information they need to address water and sanitation issues. Before submitting the TIEHR proposal, the team working on Carrera’s current project in Flint held focus groups with community members. They wanted to understand residents’ priorities and expertise from their firsthand experience responding to the public health crisis.

“We use an approach called Listening-Dialogue-Action. The first step is to listen to community members about what is happening in their community, see what questions they have about their environment and health, and talk about what solutions they would like to see put in place,” she said.

Through the preliminary focus groups, the team learned that the community members were more interested in how the information would be shared than in developing new, cheaper testing tools to measure contaminants in their water. They wanted communication tools to share information within the community. As a result, the team shifted its focus in the proposal, and ultimately the project, to working with community members to develop a mobile application to promote environmental health literacy and share water quality data.

A New Model for Community Driven Research

In addition to the focus groups, Carrera’s team is working to model and apply their vision of true community-driven research.

“Our research leadership team includes me and six Flint residents, who are fully co-researchers in every aspect of the project. My goal is to work towards building pathways for academic scholars to support the research inquiries of community scientists.”

She explained how their partnership works as a collective to advance research while also building capacity within the community.

“Our goal is to create a network of skilled investigators that communities can call on for specific concerns, and we hope to continually grow that network in the future.”