Superfund Research Program

By Adeline Lopez

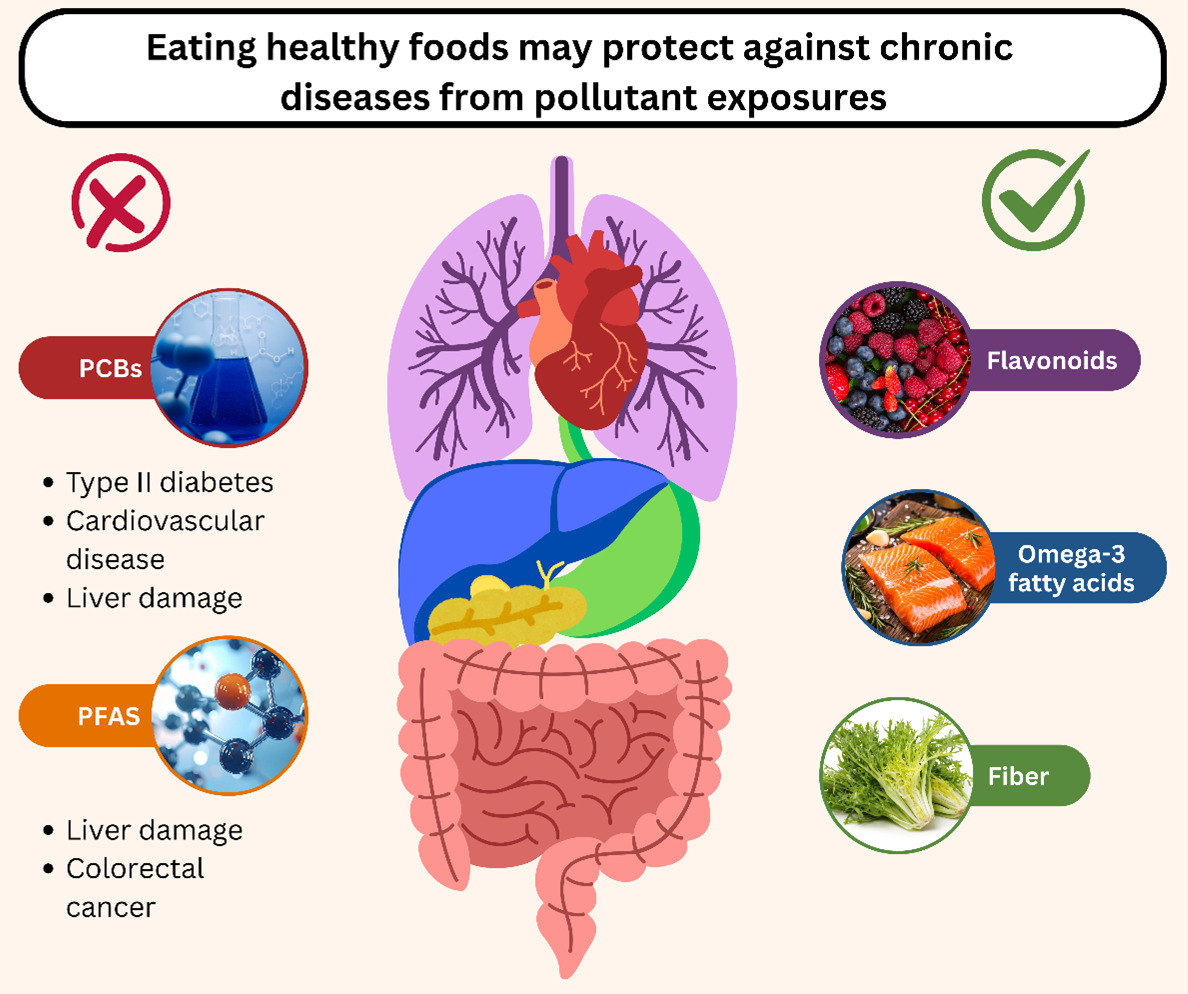

With funding from the NIEHS Superfund Research Program (SRP), researchers at the University of Kentucky (UK) SRP Center have revealed new insight into how environmental contaminants like PFAS harm the body and identified how nutrition can act as a powerful intervention to protect the health of communities.

By integrating studies in cells, rodents, and human populations, the UK SRP Center team has shed light on the important role of nutrition in protecting people from the harmful effects of pollutants and identified practical solutions for individuals to improve their health.

The Problem

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) each represent a large group of persistent chemicals found at Superfund and other hazardous sites. The substances have been linked to a variety of harmful effects, including on the immune system, reproductive system, nervous system, endocrine system, and more.

Within Central Appalachia, there is a higher risk of premature death due to chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and other inflammatory diseases that are commonly associated with environmental pollutant exposures.

SRP Solutions

(Image courtesy of the UK SRP Center)

Researchers at the UK SRP Center, originally led by Bernhard Hennig, Ph.D., study underlying mechanisms by which exposure to PCBs and other compounds can harm the body, how some components of our diets worsen these effects, and how good nutrition can protect health.

Lifestyle changes, such as diet, are practical solutions that empower individuals and communities to take control of their health.

Understanding How PCBs Harm the Body

Most of Hennig's SRP-funded research focused on how PCB exposure leads to cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

For example, using studies in cells and mice, the team gained insight into how exposure to PCBs disrupts cells that make up the inner lining of the circulatory system, called endothelial cells, and increases oxidative stress and inflammation. These steps can contribute to diseases like atherosclerosis, where cholesterol and fat build up on the walls of arteries and obstruct blood flow.

Hennig and team were the first to link exposure to low levels of PCBs with inflammation and heart disease in mice prone to obesity, even when the rodents had followed a low-fat diet.

They also uncovered complex relationships between exposure to PCBs, diet, and the microbiome, which is made up of all the microorganisms that reside in the body. For example, they found that PCB exposure disrupted the gut microbiome and altered metabolism in mice. These changes triggered an inflammatory response throughout the body and increased markers of cardiovascular disease.

The Key Role of Nutrition

Hennig was interested in healthy living, nutrition, and cardiometabolic diseases long before the UK SRP Center came to life. But it was through the Center that his interest in exploring the intersection between diet, chemical exposures, and health took flight.

“The NIEHS SRP Center has provided me and my colleagues with a wonderful platform to explore complex research involving nutrition and toxicology,” said Hennig.

Together, the team revealed how several different components of our diets — including fats, antioxidants, and fiber — can protect against the harmful effects of pollutants.

For example, the team discovered that the type of fat in the diet, and not just the amount, can make a difference in how PCBs contribute to cardiovascular disease. For example, they found that mice exposed to both PCBs and omega-6 fatty acids had more endothelial cell dysfunction and inflammation compared to mice exposed only to PCBs. Omega-6 fatty acids are a type of unsaturated fat found in processed vegetable oils, nuts, and seeds that can increase the risk of heart disease if not eaten in moderation.

In contrast, they found that nutrients such as vitamin E and healthy omega-3 fatty acids, primarily found in fish, can reduce cell damage from PCB exposure by blocking the cellular pathways that lead to oxidative stress and inflammation.

The team also identified the protective role of plant-based antioxidants, called flavonoids, against PCB toxicity. For example, in mice they found that flavonoids:

- Reduced oxidative stress and endothelial toxicity.

- Prevented endothelial cell inflammation.

- Increased antioxidant defense proteins following PCB exposure.

In humans, the team discovered that diets rich in flavonoids from fruits and vegetables can reduce the risk for PCB-associated type 2 diabetes.

Similarly, they found that inulin, a type of fiber found in vegetables, may protect against cardiovascular problems, including heart disease resulting from exposure to PCBs. A diet rich in inulin also reduced fat accumulation in the liver, protected the gut microbiome, and decreased atherosclerosis in mice exposed to PCBs. According to the team, these findings pointed to potential nutritional interventions for people who are exposed to PCBs. UK SRP Center researcher and former trainee Pan Deng, Ph.D., described this work in a video.

"I believe that embracing good nutrition is a very sensible way of confronting the fact that we live in a complex environment and experience a variety of exposures and chemical mixtures," Hennig said. "The food we eat and whether we are physically active has tremendous influence in the long term on our vulnerability to other stressors."

Tackling Emerging Health Threats

Building on their findings with PCBs, Hennig and team added another layer of complexity to their research — studying exposure to mixtures of contaminants. In particular, the UK SRP Center added PFAS as contaminants of interest.

Hennig and Deng reported that mice exposed to both PCBs and PFAS had worse liver damage, fat accumulation, and markers of cardiovascular risk compared to mice exposed to each chemical alone. Similar to their findings with PCBs, the scientists discovered that soluble fiber protected against PFAS toxicity in mice, including reducing their susceptibility to PFAS-related metabolic changes and shifts in the microbiome community.

"We are exposed to a wide range of mixtures of pollutants in our everyday lives," Hennig explained. "Many of them act through similar mechanisms to harm health, so it is important to study mixtures as well as individual pollutants. The multidisciplinary systems approach within SRP allows us to further study and understand this complexity as well identify unique interventions, such as through positive lifestyle changes and nutrition."

Zaytseva is an associate professor at the University of Kentucky studying how exposure to harmful pollutants can contribute to chronic diseases and how components of our diets can protect our health. (Photo courtesy of the University of Kentucky)

In 2023, Hennig passed the mantle to Yekaterina Zaytseva, Ph.D., who broadened the team’s focus to explore how PFAS impact the gastrointestinal system. Organs in the GI tract come into direct contact with PFAS through contaminated drinking water and food, making them susceptible to harm.

“Kentucky has a higher incidence of colorectal cancer compared to the rest of the United States,” Zaytseva explained. “Our ongoing research aims to guide interventions that can reduce disease and protect health not only in Kentucky communities but across the U.S.”

Zaytseva and colleagues are revealing how PFAS exposure may damage the intestines and possibly increase the risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Their findings show that exposure to PFOS, the most abundant PFAS detected in drinking water, reduces an important metabolic process in intestinal cells called ketogenesis. Ketogenesis is known to be protective against colorectal cancer. At the same time, PFOS exposure increases proteins associated with elevated risk of colorectal cancer. Consistent with the previous studies, Zaytseva and team suggest that certain dietary interventions, such as high fiber or ketogenic diet, may help protect the intestines from the harmful effects of PFAS exposure.

Another important component of this research is understanding how harmful chemicals, like PFAS and PCBs, are processed and metabolized in the body. Some of these changes that happen inside the body can make compounds more toxic than their original form. To understand how these potentially harmful metabolites are created, Hunter Moseley, Ph.D., co-investigator on the project, is using machine learning techniques to map metabolites to known metabolic pathways.

According to the team, this work is critical in identifying the specific biochemical processes that PFAS or other chemical exposures disrupt. This information can then help clarify how specific changes contribute to tissue damage or cancer risk.

“By revealing the mechanistic links between PFAS exposure and metabolic changes that underpin disease, our team is looking to pinpoint targets for prevention and therapeutic intervention,” said Zaytseva. “This approach strengthens the scientific basis for developing effective dietary and other strategies to protect health.”

Engaging Communities and Promoting Health

"A key challenge is to translate our research into clear, easily understandable public health messaging that helps individuals and communities learn about better nutrition options and their many health benefits,” Hennig said.

Through the Community Engagement Core (CEC), led by Dawn Brewer, Ph.D., the UK SRP Center does just that.

From left to right, UK SRP Center trainees Molly Frazar, Victoria Klaus, and Kevin Baldridge, picked blackberries for residents of a senior center in Danville, Kentucky. (Image courtesy of the UK SRP Center)

For example, they designed and implemented educational programs to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among people exposed to PCBs. Many of these interventions focus on adult populations, including older adults, who may be more susceptible to the harmful effects of hazardous exposures.

The team has partnered with the University of Kentucky Family and Consumer Sciences Cooperative Extension Service to pilot several curricula in communities. The curricula are currently being offered across Kentucky through the Extension.

For example, the team found that their “Body Balance: Protect Your Body from Pollution with a Healthy Lifestyle,” program effectively improved environmental health literacy in the community, as did their nutrition education programs for older adults.

Similarly, their community-based participatory research approach resulted in a sustainable source of blackberries and nutrition education being provided to older adults through the BerryCare Extension program. The most recent piloted curriculum series that is available through Cooperative Extension is a Sustainable Eating curriculum that encourages healthy eating to improve human and environmental health.

Learn more about their work in the NIEHS podcast "Eating a Healthy Diet to Protect Against Pollution."