May 1, 2024

Epidemiologist Heather Volk, Ph.D., studies the interplay of genes and environment on children's health. (Photo courtesy of Heather Volk)

As an NIEHS grant recipient and associate professor at Johns Hopkins University, Heather Volk, Ph.D., investigates how interactions between environmental factors, such as air pollution, and genetic factors, like mutations, lead to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children.

“What better way to help kids thrive than understanding how the environment affects their health,” Volk said. “The cool part about the environment is that it’s something we can work to change.”

Volk became interested in gene-environment interactions in ASD after receiving an NIEHS grant to pursue postdoctoral research training at the University of Southern California.

“When I first started researching autism, the prevalence of ASD in 8-year-olds was 1 in 110, and now it’s around 1 in 36,” Volk said. “In the early 2000s, things were sort of stuck in terms of answering questions around what causes autism. But researchers were drawing connections between air pollution and other brain outcomes, so looking at the environment for potential impacts on ASD made sense for me.”

Identifying Gene-Environment Interactions

A researcher on Volk's team isolates DNA in the lab. (Photo courtesy of Heather Volk)

Part of Volk’s research explores how environmental exposures in utero can lead to neurodevelopmental disorders later in life. For example, she and her team found that mothers with a specific genetic variant who were exposed to higher levels of traffic-related air pollution while pregnant had greater chances of having children with ASD.

Another study found an increased likelihood of ASD in kids who had greater exposure to ozone — a major component of smog — and more deletions or duplications in certain regions of DNA.

Volk’s research often relies on data from long-running studies like the Early Autism Risk Longitudinal Investigation (EARLI), a formerly funded NIEHS project that has followed a cohort of 264 families of children with ASD since 2008.

For example, Volk’s team is collecting teeth from children enrolled in EARLI and similar studies to identify what contaminants the kids may have been exposed to during fetal development.

“Families have loved sharing teeth, and it’s been exciting to use teeth as a tool for environmental epidemiology,” Volk said. “Contaminants are mineralized into layers of the teeth, similar to the growth rings in trees, creating a unique biological hard drive that keeps a record of past exposures.”

Volk emphasized that studies like hers are possible thanks to the investigators who started EARLI, and because of EARLI project coordinators, who play a crucial role in developing strong relationships with many study families.

“We return lay summaries of study findings to families so that they can understand how their time and effort has contributed to helping us learn about children’s health,” Volk said.

The EARLI team also intends to help families adapt to ASD diagnoses through discussions about healthy lifestyles, navigating school, and other social challenges.

Building Bridges and Research Infrastructure

As a pioneer in her field, Volk sees ample room for growth.

“Up until 10 to 12 years ago, genetics and the environment were two separate factions in autism research,” she said. “Even looking at today’s literature, there are maybe 15 publications that truly investigate the joint effects of the environment and genetics on ASD.”

She encourages more colleagues to study how genetics and environmental toxicants interact to influence ASD. But to do that, researchers need accommodating research infrastructure.

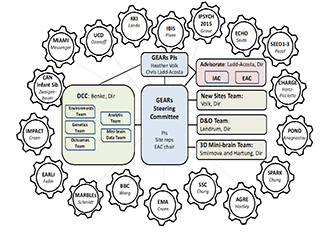

GEARs stands for "combining advances in Genomics and Environmental science to accelerate Actionable Research and practice ASD." This graphic represents the complexity of integrating 18 cohorts. (Image courtesy of Heather Volk)

“Everyone has their own research infrastructure — the policies, resources, and capacity needed to conduct research,” explained Volk. “Navigating these differences is one of the greatest challenges for moving collaborations toward a common goal and answering these big research questions.”

With Christine Ladd-Acosta, Ph.D., Volk aims to promote collaborative research through GEARs, part of the NIH Autism Centers of Excellence program. With funding from NIEHS, as well as the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, GEARs will pool data from 18 ongoing population studies — including the EARLI cohort — which together comprise 175,000 participants.

“Using these 18 cohorts, we are trying to roll out large-scale analyses of ASD and gene-environment interactions,” explained Volk. “Out of everything I’ve done in my career, this collaboration is what I hope changes the field.”

From Mentee to Mentor

For Volk, success is a group effort.

Volk attributes her success to the village of collaborators, mentors, and colleagues who have become her closest friends. "Much of the work I do would not be possible without them," she said. (Photo courtesy of Heather Volk)

“NIEHS has been incredibly supportive of my career, from when I was a post-doc all the way through now,” she said. “Since receiving the training grant that kick-started my career, several of my projects have been funded through other NIEHS funding mechanisms and larger institutional grants.”

Now, as a principal investigator, Volk is committed to sharing lessons she learned along the way.

“Throughout my career, I have been gifted incredible mentors with backgrounds in environmental health sciences, epidemiology, and genetics,” said Volk. “I hope to support my own trainees in the same way that I was supported, by helping them identify and play to their own strengths while teaching them to build a team that can alleviate their weaknesses.”

Working with junior researchers is one of Volk’s favorite duties. Their drive and initiative are what move ideas to action, she explained.

“I get to see the great things trainees come up with on their own,” Volk said. "And what’s exciting is not necessarily what I find, or what I can accomplish, but what I can help trainees build for our field moving forward.”