Superfund Research Program

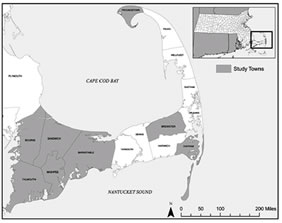

Prenatal exposure to a chemical solvent can put babies at an increased risk for birth defects, according to a study published in the September 2009 issue of Environmental Health . The study, led by Dr. Ann Aschengrau of the Boston University Superfund Research Program, explored the relationship between a mother's exposure to perchloroethylene (PCE) and the incidence of birth defects in children born around Cape Cod, Mass. between 1969 and 1983.

PCE, a chlorinated ethylene, is classified as a potential human carcinogen by the Department of Health and Human Services. It is a commonly-used solvent in the dry-cleaning industry and as a metal degreaser. The mothers in this study were exposed to PCE through the municipal drinking water supply. Over 660 miles of asbestos cement pipes were installed in the area from the late 1960s through 1980. Prior to their installation, the inner surface of the pipes was coated with vinyl toluene resin dissolved in PCE to improve the taste of the water.

SThe manufacturers who installed the lining thought that the highly volatile PCE would evaporate prior to installation, but their assumption was wrong. When the water was tested up to 20 years later, municipal authorities learned that PCE had been leaching into the water supply for years and, in some localities were nearly 200 times the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's 1980 maximum contaminant level of 40 µg/L. Once the contamination was detected, the pipes were cleared with a flushing process and are now in compliance with EPA standards.

Aschengrau and her team of researchers painstakingly compiled municipal water records and matched them with birth certificates to find women exposed to the solvent during their pregnancies. Of the women contacted who lived in the area during the time of contamination, 70%—over 2,000 people—responded. Cleft lip and palate and neural tube defects were three times more common among babies who had been exposed in the womb to PCE than among babies who were not exposed.

This work stands out because Aschengrau was able to single out the ingestion of PCE as a single exposure route. Through leaching and transport models, she was able to estimate historical PCE exposures in the Cape Cod area. However, due to the small size of the study, Aschengrau recommends follow-up studies. She'd like to conduct studies across Massachusetts in order to obtain a larger sample size. "Because PCE remains a commonly used solvent and frequent contaminant of ground and drinking water supplies," she said, "it is important to understand its impact on the occurrence of congenital anomalies."