- Andrew George, Ph.D. – Forging Partnerships to Reach and Empower Rural Well Water Users

- Pete Raynor, Ph.D. – Protecting Worker and Community Health from Environmental Hazards

- Abby Mutic, Ph.D., M.S.N., C.N.M. and Nathan Mutic, M.S., M.A.T., M.Ed. – Innovating Environmental Health Communication

- Mary Crocker M.D. – Protecting Kids From Wildfire Smoke: How Research Informs Practice

- James Stafford, Ph.D. and Michael Rountree, Ph.D. – An Education in Epigenetics: Improving Students’ Environmental Health Knowledge

- Ayca Erkin-Cakmak, M.D., MPH, and Ana Maria Mora, M.D., Ph.D. – Researchers Trace Health Effects of Early-life Exposure to Pesticides and Other Pollutants

- Liliana Aguayo, Ph.D. – Helping Families Make Heart-Healthy Choices

Andrew George, Ph.D. – Forging Partnerships to Reach and Empower Rural Well Water Users

June 4, 2025

Andrew George, Ph.D., is the UNC SRP Center’s community engagement coordinator and spends his days working with community partners and UNC’s study participants. (Photo courtesy of Andrew George)

In North Carolina, 2.4 million people — nearly a quarter of the state’s population — rely on private wells. About 25% of those wells are contaminated with metals, such as arsenic, manganese, and lead, at levels above federal safety standards, according to NIEHS-funded research. For Andrew George, Ph.D., helping protect North Carolinians from those pollutants is a full-time job.

As community engagement coordinator at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Center for Public Engagement with Science (CPES), which NIEHS supports, George connects communities with information about the health effects of metal exposures and resources for testing and treating their well water.

“We engage the community in participatory science — we don’t just parachute in and disappear with the research,” George said. “We communicate our research findings to the community. That’s part of our formula.”

Natural Connections

George traces his interest in environmental health and community outreach to growing up in Florida. The local swamp ecology and fauna fascinated him so much that, as a middle schooler, he volunteered at a local nature museum where he got his feet wet engaging with public audiences.

A couple years after graduating with a bachelor’s in political ecology from Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina, George became the executive director of the Southern Appalachian Biodiversity Project, a small nonprofit focused on forest habitat conservation. Success hinged on building strong partnerships with communities and local organizations, George explained. More than 30 years later, he still collaborates with some of the same environmental leaders from his nonprofit days, while also cultivating new partnerships.

“I think a lot of our success at CPES is because we value small nonprofit groups, small community-led groups, and neighborhood organizations,” George explained. “We look at them not just as members of ‘fence-line communities’ — places close to hazardous waste-producing facilities — who can tell us what’s going on, but as our active partners in trying to address some of the problems.”

Uncharted Waters

In the 2010s, the UNC Superfund Research Program (SRP) team, funded by NIEHS, discovered that North Carolina has a serious problem with naturally occurring arsenic. Arsenic can affect human health in numerous ways, depending on the length and extent of exposure, and is a metal of concern for SRP. The North Carolina Slate Belt, a geological feature underlying the Appalachian foothills, harbors natural arsenic that leaches into groundwater and can invade wells, explained George, who also supports UNC SRP efforts.

State law requires well testing at the time of construction but at no time thereafter, even upon sale of a property. When George joined UNC in 2015, he learned that North Carolinians in remote areas and people of color were under-represented in publicly available well water data. He suspected that these groups might be disproportionately exposed to metals.

George collects information from a North Carolina property owner about his well water. George and the UNC SRP team emphasize outreach to rural and under-resourced communities. (Photo courtesy of Andrew George)

With the guidance and facilitation of local partners across the state — such as a local environmental steward called the Lumber Riverkeeper, and the Union County environmental health department — George sought to continue and expand the UNC SRP team’s decades-long outreach to communities.

“We recruited deliberately, to make sure we had a good sample of well users in our study, representative of the people in our state,” George explained. “Our community partners were critical to our success.”

The UNC SRP team and their partners found creative ways to conduct testing, including sending well tests directly to homes, with explicit and easy-to-understand directions. Residents could collect a water sample from their tap and mail it to UNC free of charge.

If the researchers detected high levels of metals, they worked with residents to reduce exposures. For example, the UNC SRP team immediately provided affected residents with a filter pitcher certified to remove contaminants.

“We got these filters to people within 12 to 24 hours,” George shared. “It helps, when you call folks up and you have bad news, to at least give them peace of mind in the short term.”

“We have been able to provide filters to study participants free of charge, a near-term solution that has been especially important for low-income participants,” added CPES director and UNC SRP Community Engagement Core (CEC) leader Kathleen Gray, Ph.D.

Wellsprings of Local Potential

Building off earlier work, UNC SRP more recently investigated arsenic exposure in well water in Union County, within the North Carolina Slate Belt. Working with partners such as the Union County Health Department, the nonprofit Clean Water for North Carolina, the county’s NAACP chapter, and NC Cooperative Extension at North Carolina State University, the team has knocked on doors, handed out flyers, left information in restaurants, and posted information on local government television to recruit well users for their research.

George demonstrates well water collecting and testing techniques for UNC students. (Photo courtesy of Andrew George)

After analyzing their data, the team made a troubling finding. Nearly 20% of the wells were contaminated with arsenic, with some significantly above the federal limit. The CEC’s research translation team and SRP investigators immediately reported the results back to the study participants and sent pitcher filters to reduce exposures.

Then, the team held a community education meeting, where they shared their data, plus county resources for well rehabilitation and other solutions for addressing the contamination.

“We have a lot of expertise on research translation,” George stated. “Sarah Yelton, the UNC SRP research translation coordinator, helps us make sure our materials are tight, coherent, and easily accessible to lay audiences.” Yelton is the CPES environmental education and citizen science program manager, is a member of the CEC, and leads communications strategy and materials development.

What happened after the meeting still amazes George. Well users in one Union County town used the personalized report-back data to lobby the town government for water line extensions, which would connect their residences to municipal water lines. The town council voted to support the extensions, provided design funding, and is now working to secure construction funding, according to George.

“This is exactly what we’re hoping to have happen with our work,” he said. “We get people thinking about the issue. They directly apply our data to the problem. They work with their communities, partners, neighbors, and local health departments to think about creative solutions. Then, hopefully, in the end, they get a permanent, long-term solution that protects their health and their children’s health.”

Partnership Power

The dedication of community partners cannot be overstated, George noted. For example, UNC SRP has worked with Jefferson Currie II, the Lumber Riverkeeper, since 2018, when they conducted a study of Hurricane Florence’s impact on private well water quality in Robeson and surrounding counties.

Currie is a member of the Lumbee Tribe that comprises a significant portion of the county’s population, so he has a deep connection with the local community.

“He knew where to go, he knew how to seek out potential people for our study,” George said of Currie. “We went down some dirt roads and to some areas that, I think, previous studies have probably overlooked.”

AAs they collected data about water quality post-hurricane, the team also asked questions about residents’ testing habits. Of 476 private well users enrolled for testing, the team found over half had never checked their well water. Their findings also revealed clear disparities.

“We found that high-income, White populations had 10 times greater odds of testing their water,” George explained. “Also, they had over four times greater odds of treating their water than low-income, non-White populations.”

Lately, George and UNC SRP colleagues have again turned their attention to Robeson County. They will be gathering data to help answer community questions and concerns about how local contamination may be affecting a culturally important site for the Lumbee Tribe. Together with partners, the team will design and conduct community-engaged research into arsenic sources in drinking water. They will also try to address other water quality issues potentially affecting the community’s health.

“Part of why I like Andrew is we’re both here for the same reason, which is to do something meaningful,” Currie said. “We can’t change the world — no one person can do that — but you can help your little corner do a little better. Andrew is doing what he’s doing for the right reason, which is to help people.”

Pete Raynor, Ph.D. – Protecting Worker and Community Health from Environmental Hazards

May 6, 2025

Raynor became director of the MWC in 2020. Prior to that, Carol Rice, Ph.D., led the consortium at the University of Cincinnati for more than 30 years.

“When I took over as MWC director, the advice Carol gave me was just to make sure that the trainers can continue doing the good work that they do,” said Raynor. “So that’s how I see my role – I facilitate the work of the 13 centers and then get out of the way.” (Image courtesy of Pete Raynor).

When more than 50 gallons of gasoline spilled at an Ohio automobile plant, a team of trained workers rapidly responded to contain the spill. Without this swift response, workers and nearby residents may have faced danger from an explosion or fire, inhaling gas fumes, or other impacts to the surrounding environment.

This is one of many of success stories where workers have kept themselves, their co-workers, and their communities safe, thanks to the Midwest Consortium for Hazardous Waste Worker Training (MWC). Funded by the NIEHS Worker Training Program, the MWC has trained hundreds of thousands of people since it was first established in 1987.

“We train workers, first-responders, and community members to safely respond to a range of potentially dangerous scenarios,” said Pete Raynor, Ph.D., MWC principal investigator.

Administered through the University of Minnesota, the MWC is made up of 13 training centers spanning nine states. The training centers include universities, community colleges, labor-affiliated programs, community-based organizations, and a tribal nation. Although each center is unique, they all have the same goal: to build regional capacity to respond to environmental hazards.

MWC training centers are in Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Ohio, Tennessee, and Wisconsin. (Image courtesy of the MWC).

“I think what makes MWC so strong is that our network serves so many different populations, all of which have different needs,” said Raynor. “When our centers come together, we share best practices and learn about emerging occupational health topics in a way that strengthens the entire consortium.”

Meeting Worker and Community Needs

Each training center is responsive to the needs of their local communities and workforce.

For example, one training center, Emergency Response Solutions International (ERSI), trains emergency response teams at Ford Motor Company manufacturing facilities, which are highly concentrated in the Midwest. ERSI instructors teach auto plant workers a range of skills, including confined space rescue, first aid, and hazardous waste response. These courses provide workers with the knowledge to safely prepare for and respond to emergencies in the workplace.

“Auto manufacturing plants are huge, and it can take an outside responder a long time to the reach the site of an emergency,” said Raynor. “Having teams of workers on site that are prepared to contain and minimize emergencies until outside responders arrive can save lives.”

Trainees observe a pallet of batteries during an in-plant lithium-ion battery awareness program. (Photo courtesy of the MWC).

More recently, ESRI developed a curriculum for lithium-ion battery safety. Workers and community members frequently use devices containing these rechargeable batteries, including electric vehicles, power tools, cell phones, laptops, and more. While these batteries offer many benefits, they can become a fire or explosion hazard.

“Lithium-ion battery fires are difficult to extinguish, and they release toxic fumes that pose significant health risks,” said Raynor. “As these devices become more common in workplaces and our daily lives, it’s important that people are aware of the potential dangers and that workers and emergency responders know how to manage the hazards.”

Trainees practice deploying a fire blanket as part of an electric vehicle fire response. (Photo courtesy of the MWC).

Opioid awareness and safety training are also needed for workers in the Midwest region. Workers in certain occupations, such as emergency medical services, law enforcement, and environmental services, face a high risk of exposure to opioids when responding to overdoses, investigating drug crimes and labs, analyzing contraband, and performing cleanup.

One MWC training center, the Cincinnati Interfaith Workers Center, delivers opioid awareness training to groups of young workers in restaurants and hotels to help them recognize and respond if a customer or co-worker is having an overdose. Other MWC training centers have delivered opioid awareness and emergency response training to transit workers, U.S. Coast Guard personnel, social workers, tribal communities, and college students.

Responding to Disasters

MWC training centers also prepare workers and communities to respond to weather-related disasters.

“Major flood events and wildfires are becoming more common in our region,” said Raynor. “MWC training centers teach groups from emergency responders to community members about how to stay safe during environmental cleanup following weather-related disasters.”

For example, the training center at the University of Tennessee (UT) prepares utility workers to safely navigate post-storm environments as they work to reestablish the electric grid. This training involves emergency responder safety after hurricanes, safe driving during storms, electrical safety after a storm, and working near moving water. Notably, the UT center delivered post storm safety training to water utility and emergency management workers in North Carolina just weeks before Hurricane Helene hit the region in September 2024.

“These participants applied what they learned right away and were grateful to have had the training,” said Raynor.

Staying Ahead of the Curve

One thing that Raynor is particularly excited about is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in emergency response.

“AI is everywhere, and we think it’s going to be especially useful in hazardous waste and emergency response,” said Raynor. “We want to be ahead of the AI curve – not playing catch-up.”

MWC is currently developing an application that training participants can use when responding to hazardous materials incidents. The app will be connected to databases with information that can guide responders’ decision-making. For example, by integrating data on local weather conditions and details of a chemical spill, the app will be able to overlay an evacuation radius on a map of the surrounding area. Then, emergency response teams can use the map to quickly evacuate affected areas.

“What’s important to remember is that a trained responder will always be on the other end of the app to verify the information,” said Raynor. “We are never going to replace the human aspect of emergency response, we just hope to improve it.”

Those people, and their stories, are what keep Raynor and the MWC trainers going.

“We get lots of stories about how our training has helped save someone’s life or contain a spill to protect a nearby community,” he said. “When you hear that the curricula and programs you’ve been working on actually benefit people – that’s what’s really rewarding.”

Abby Mutic, Ph.D., M.S.N., C.N.M. and Nathan Mutic, M.S., M.A.T., M.Ed. – Innovating Environmental Health Communication

April 30, 2025

In this highlight, we speak with Abby Mutic, Ph.D., M.S.N., C.N.M., and Nathan Mutic, M.S., M.A.T., M.Ed., both at Emory University, about their shared commitment to ensuring that research is communicated effectively so that people can make informed decisions.

“Over the years, we have featured individuals and their contributions to environmental public health. It is not often that we get to spotlight a family working together to advance this field,” said NIEHS Health Specialist Liam O’Fallon, M.A.

After meeting during graduate school at Vanderbilt University, Abby and Nathan married and began careers in healthcare and education — Abby as a nurse midwife and Nathan as a high school biology and chemistry teacher. While caring for patients, Abby became interested in how the environment affects pregnancy and health outcomes for mothers and their children.

“Many of the women coming to the clinic worked in farming or factories and had concerns about their exposures and whether those exposures were safe for their pregnancies, their health, and their families’ health,” Abby said. “I became really interested in answering those questions.”

Collaborating in the Field

“Synthesizing environmental health literature in a systematic and clear way is challenging work, but is so important for the general public,” Abby said. (Photo courtesy of Emory University)

When Abby started at Emory, she continued supporting farm workers, joining the Girasoles Research Program. The program, led by Linda McCauley, Ph.D., R.N., focuses on occupational and environmental health concerns of Florida farm workers, a group with an increased risk for heat-related illnesses.

“As nurse researchers leading the Girasoles study, we were able to connect biometrics, like blood sugar and kidney function, with how workers felt as temperatures change through the day,” said Abby. “We broke down complex information into clear terms, making it easier for research participants to understand the health impacts.”

During summer break from the teaching year, Nathan joined Abby in the field in Florida to help with data collection. Together, they developed a protocol to help researchers share health data with participants. It was during this trip that he discovered a new interest in environmental health.

“My teaching background prepared me to quickly evaluate where someone’s knowledge is and how to build on that knowledge to share information,” said Nathan.

Harnessing Social Media

“The support of the EPA and NIEHS was invaluable for providing an opportunity to exchange ideas,” Nathan said. (Photo courtesy Emory University)

Nathan shifted from teaching to supporting the Southeast Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit (PEHSU) and the Emory Children’s Environmental Health Center (CEHC). There, he became passionate about clear scientific communication among scientists, clinicians, and communities tackling children’s environmental health.

After a meeting between the PEHSU and CEHC networks, Nathan and collaborators at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the University of Southern California launched a national social media campaign about children’s environmental health with funding from an NIEHS administrative supplement. The campaign, which built on findings from the 2017 NIEHS/EPA Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Centers Impact Report, allowed organizations in the PEHSU and CEHC networks to tailor posts for their own audience.

“The campaign was only possible because of the collaboration and leadership from each center,” said Nathan.

Nathan found that shared goals and authentic relationships with community groups — like translating environmental health research findings into practical information for reducing exposures to smoke, allergens, and other pollutants — lay the groundwork for effective engagement. While no longer at the PEHSU, Nathan carries those values into his current role as the Assistant Dean of Research Operations at the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing at Emory University.

Advancing environmental health communication

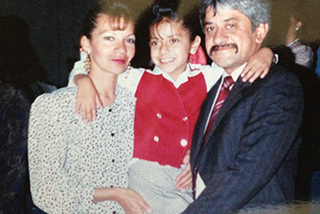

Abby and Nathan Mutic (center) with partners from the Center for Black Women’s Wellness at a community outreach event. (Photo courtesy of Abby Mutic)

Abby now serves as the director of the Southeast PEHSU and is a professor at the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing at Emory University. She collaborates with experts in nursing, toxicology, education, and other fields to turn complex environmental health data into clear, actionable information that directly benefits communities.

Like Nathan, Abby centers her work around community voices.

“It’s really important that my research is relevant to what folks in the community are most concerned about with their kids and their pregnancies,” she said.

Abby also collaborates with Sun Joo Grace Ahn, Ph.D., of the University of Georgia, on a virtual immersive experience that simulates asthma triggers in a home setting, helping participants understand how to improve indoor air quality. The project is supported by the NIEHS-funded Center for Children’s Health Assessment, Research, Translation and Combating Environmental Racism (CHARTER), which is directed by Linda McCauley, Ph.D., R.N.

“Talking about environmental health can feel overwhelming if people think they can’t change their environment,” said Abby. “Our simulation empowers people to reduce their air pollution exposure.”

In another study, funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and CHARTER, Abby works with early learning centers in the Atlanta area to measure indoor air exposure using silicone wrist bands worn by pre-K students. Her goal is to study how these pollutants affect children and if they can communicate respiratory symptoms to their parents.

Abby Mutic presents on the risk of lead paint exposure to community partners. (Photo courtesy of Abby Mutic)

“Building strong relationships with teachers was key to ensuring student learning and play was not interrupted by the study procedures and to build trust with caregivers,” Abby said.

Although they no longer work side by side, Abby and Nathan continue to support each other’s contributions to communicating environmental health to researchers and communities alike.

“I’m thrilled to see growing attention on translating environmental health research for communities,” Abby said. “Identifying how to effectively communicate this data is a science in itself, and communities benefit when we make environmental health information clear and meaningful.”

Mary Crocker M.D. – Protecting Kids From Wildfire Smoke: How Research Informs Practice

April 29, 2025

Mary Crocker also holds a Master of Public Health in program planning and evaluation. (Photo courtesy of Mary Crocker)

As a young doctor at Seattle Children’s Hospital, Mary Crocker, M.D., faced a clinical challenge from an unanticipated source: wildfire smoke. Her patients were presenting with exacerbated asthma symptoms from exposure to smoke, and when parents asked how to best protect their children, Crocker wasn’t always sure what to tell them.

“It was frustrating that I didn’t have great advice to share with them because I didn’t learn about wildfire smoke in medical school,” she said. “That’s when I decided I needed to do more.”

As she read about wildfire smoke and children’s health, Crocker realized there were few evidence-based interventions to protect children at risk of exposure. She was inspired to develop these interventions, but she needed more time for research.

Crocker then joined the University of Washington Pediatric and Reproductive Environmental Health Scholars (PREHS) program. The NIEHS-funded program provides pediatricians with protected time to develop their research capacity, conduct community-engaged research, and translate research findings into clinical interventions.

Perks of PREHS

Before PREHS, Crocker had some research training through a fellowship with the National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center. Through a Peru-based project, she examined the health effects of indoor air pollution from burning wood for fuel.

Crocker uses an ultrasound to detect an infant’s lung infection for her Fogarty Fellowship research. (Photo courtesy of Mary Crocker).

“One of the outcomes we studied was pneumonia in children,” said Crocker. “That was my first opportunity to conduct environmental health research, and it coincided with my interests in lung health.”

She credits her Fogarty fellowship and a career development award from Seattle Children’s Hospital as steppingstones to PREHS. According to Crocker, PREHS classes in environmental epidemiology, qualitative research methods, and data analysis significantly improved her research skills.

“PREHS course work has strengthened my ability to design rigorous studies, understand data analysis, and interpret results,” she explained.

Crocker added that the biggest perk of PREHS is mentorship. Her primary mentor, Catherine Karr, M.D., Ph.D., has helped Crocker tap into resources she didn’t know existed, like funding opportunities through NIEHS or research support through different academic departments.

“I think PREHS will benefit me for a long time,” said Crocker. “I’m able to take what I learn from my research and use it in clinical practice. I can share my findings with patients and say, ‘This is what I found, and here are some things that are helpful.’”

Wildfire Smoke and Children's Respiratory Health

Through PREHS, she has become confident giving advice to families on how to reduce their exposure to wildfire smoke – informed by her work summarizing how wildfire smoke influences respiratory health for the estimated 7.4 million children exposed annually, 700,000 of which have asthma.

“The number one thing I tell families is to know your air quality,” Crocker said. “I show them how to check the air quality index on apps and websites and tell them what actions need to be taken at different thresholds.”

Protective measures Crocker recommends include staying inside if possible, wearing an N95 mask if going outside, ensuring smoke cannot enter the home, and installing a home air filter to remove smoke pollution.

“For some children, wildfire smoke exposure may trigger mild respiratory symptoms, like nasal secretions or coughing,” Crocker explained. “But for others, it can be more severe, like wheezing, coughing, and shortness of breath that can lead to hospitalization and be life-threatening.”

However, to effectively prevent wildfire smoke exposure, physicians need to know when to step in and what to tell their patients. For Crocker, this was a challenge when she first started at Seattle Children’s Hospital, and she was curious if other doctors had a similar experience. To find out, she conducted a survey of pediatric pulmonary providers in Washington state.

“We asked about different components of wildfire smoke and how to manage it in a clinical setting, and we identified many opportunities for improvement,” said Crocker. “For example, most providers knew what the air quality index was, but not all were familiar with how it is calculated. Also, not all providers felt confident helping families prevent exposure.”

To bridge this gap, Crocker has taken a more active role in pediatric resident training, developing lesson plans for how physicians can address wildfire smoke. She also supports the use of interactive lectures, case studies, and perhaps most importantly, pediatric board exam questions focused on wildfire smoke.

Crocker, seated center left, gathered with other PREHS scholars in North Carolina for the 2023 retreat. (Photo courtesy of Steve McCaw / NIEHS)

Centering Community

Prior to PREHS, Crocker collaborated with the Public Health Seattle and King County Asthma Program, which pairs environmental home inspections with education to support families of children with asthma.

As a PREHS scholar, Crocker has continued working with her local public health department to make the services available to more families. She developed a protocol for virtual home visits, taking into consideration concerns identified by families of children with asthma.

According to Crocker, interventions like this new protocol would not be effective unless informed through community-engaged research.

“Engaging communities in research is essential,” explained Crocker. “We can do research about communities very easily, but if you want to make a difference and improve health, you need to listen to the individual voices within that community.”

James Stafford, Ph.D. and Michael Rountree, Ph.D. – An Education in Epigenetics: Improving Students’ Environmental Health Knowledge

April 17, 2025

Nzumbe president, James Stafford, Ph.D., (left) and chief scientific officer, Michael Rountree, Ph.D., (right). (Photos courtesy of Rountree and Stafford)

What do a rust-colored fungus and a furry creature with horns have in common? Both are being used to teach students how the environment affects human health. The fictional character and fungus are components of two educational tools – an online game and a laboratory kit – developed by small business Nzumbe, Inc. with funding from NIEHS.

"We want to teach people how their environment impacts their epigenome in ways that can improve or harm human health,” said Nzumbe’s president, James Stafford, Ph.D.

Exposures to chemical compounds can lead to epigenetic changes, which can determine which genes are turned on or off. Although many epigenetic modifications are part of normal development and aging, environmental factors may cause epigenetic changes that lead to a range of health conditions, including autoimmune diseases, neurodevelopmental disorders, and cancers.

From Therapeutics to Teaching Tools

“Nzumbe was initially focused on developing epigenetic therapies for cancer and other diseases, but we have shifted gears to creating educational products,” said Stafford. “NIEHS funding was instrumental in broadening our company’s mission to include education.”

Founded in 2012 by Stafford, Tommy Pham, M.B.A., and Mitch Turker, Ph.D., Nzumbe quickly brought on epigenetics expert Michael Rountree, Ph.D., as chief scientific officer. Rountree’s expertise with the fungus Neurospora crassa – commonly called red bread mold – was key to some of the company’s initial endeavors to develop disease treatments.

“The Neurospora fungus has the same epigenetic marks as humans,” he said. “This is especially useful when trying to better understand human diseases triggered by epigenetic changes.”

Now, with funding from two NIEHS small business grants, the Nzumbe team is developing a laboratory kit for undergraduate students that uses the N. crassa model to demonstrate how environmental exposures can alter gene expression.

Experimenting With Fungus

To develop the laboratory activity, the team created a modified N. crassa strain engineered with an epigenetic reporter gene that restricts growth. The reporter gene is highly responsive to environmental exposures, allowing students to test how an array of environmental factors may alter fungal growth through the epigenome.

“The Neurospora model is simple, safe, and inexpensive, which makes it an ideal system to teach about environmental epigenetics in the classroom or at home,” said Rountree.

First, teachers use educational modules developed by Nzumbe to teach about epigenetics, including how environmental exposures can influence gene expression. Then, students apply these concepts in the lab. For example, by changing the fungus’s environment, such as temperature or nutrient source, the students may partially or fully reactivate the epigenetic reporter – allowing the fungus to resume growth.

“The advantage of using this reporter gene is that it provides the students with an outcome that is easy to observe and measure – in this case, growth rate – based on the expression level of the reporter gene,” said Rountree.

Gaming Gene Expression

When students first meet their EpiMon (left), the character is mostly blue with yellow fur around its neck and big, blue eyes. These traits will change based on the choices students make as they navigate through the fictional world (right, with blue EpiMon in center) and whether they answer questions correctly. (Images courtesy of Rountree and Stafford).

The Nzumbe team also created an online game called EpiMon.

“Games make learning more interactive, engaging, and fun,” said Stafford. “We wanted to lean into these attributes to teach students how lifestyle choices and environmental exposures can impact health.”

To accomplish this, Nzumbe scientists worked with software developers to create a game in which students guide their character, called an EpiMon, through a lush fictional world filled with forests, streams, and gardens. As students explore their surroundings, they must make choices – like food harvesting, fishing, cooking, and sleeping – that will determine their character’s environmental exposures, lifespan, and overall health.

The EpiMon starts out as a blue furry character. These physical traits change depending on the type of food the player chooses to harvest and eat, for example. Collecting too much of an easy to access, but less healthy food may result in an EpiMon with brown fur and red eyes, while investing the time to harvest more nutrient dense food may cause the character to sprout a tail.

“These physical changes serve as visible cues to help the students understand that the choices they make and environmental exposures they encounter influence how genes are expressed,” said Stafford.

Players can also send their EpiMon on “quests,” which serve as the game’s formal educational component. In one quest, students answer epigenetics questions to defeat a fire-breathing beast. Completing quests grant advantages, like a UV-blocking balm, to help counter environmental exposures.

“The rewards are designed to teach students about prevention,” said Stafford. “We want them to know there are steps they can take to reduce exposures that may contribute to poor health.” As a companion to the EpiMon game, Nzumbe worked with education experts to design web-based environmental health modules, covering topics like environmental epigenetics and endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

Expanding Access to Engaging Science Education

The Nzumbe team plans to test the game and laboratory kit in undergraduate science classes, focusing on community colleges or small liberal arts colleges. Once launched, the game can be adapted for middle and high school students by adjusting the educational content.

“Ultimately, we hope these products will help students understand that our environment impacts our health – and encourage them to make decisions that can prevent or reduce their risk of disease,” said Rountree.

Ayca Erkin-Cakmak, M.D., MPH, and Ana Maria Mora, M.D., Ph.D. – Researchers Trace Health Effects of Early-life Exposure to Pesticides and Other Pollutants

April 10, 2025

Erkin-Cakmak contributes her expertise on cardiometabolic outcomes in children and young adults.

Two NIEHS-funded clinicians-turned-researchers have launched a collaborative research project using data from the same epidemiological cohort study where they first met—at the University of California (UC), Berkeley. Ayca Erkin-Cakmak, M.D., MPH, and Ana Maria Mora, M.D., Ph.D., are analyzing data from the 25-year-old CHAMACOS cohort study to investigate the association between early-life exposure to mixtures of persistent organic pollutants and cardiometabolic outcomes in young adulthood.

They received a pilot award from the NIEHS-funded Environmental Research and Translation for Health (EaRTH) Center at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), to pursue this offshoot research. Erkin-Cakmak and Mora cut their teeth on epidemiology research in the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS) study at UC Berkeley. CHAMACOS means “little children” in Mexican Spanish.

Mora has expertise on the health effects of pesticides and other environmental toxicants.

Brenda Eskenazi, Ph.D., of UC Berkeley started the study of over 600 mother-child pairs in the Salinas Valley, on the central coast of California, in 1999. CHAMACOS has become the longest-running birth cohort study examining how pesticides and other environmental exposures affect the health of children, adolescents, and young adults in an agricultural community. It has also given rise to many spin-off studies, including those by Erkin-Cakmak and Mora.

CHAMACOS researchers have collected a broad spectrum of data on the cohort’s children, including on physical growth, endocrine system health, lung function, neurodevelopment, and risk-taking behaviors. They have tracked the health effects of pesticides and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs)—a class of endocrine-disrupting flame retardants—as well as other chemicals.

Teaming Up to Meet Research Challenges

Both doctors were drawn to graduate work with CHAMACOS due to their interest in how chemical exposures affect health and in finding ways to reduce these exposures. Even after Erkin-Cakmak took a position at UCSF and Mora continued as a researcher at UC Berkeley, they both knew the CHAMACOS study’s rich data held the potential for more breakthroughs. So, they decided to join forces.

A research assistant measures a CHAMACOS child participant, now a teenager, to gather benchmark data for the cohort study. (Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley)

“We thought it would be great to combine my expertise on pesticides and other environmental toxicants with Ayca’s knowledge of cardiometabolic outcomes and endocrinology, in general,” Mora related.

With their current EaRTH Center funding, Mora and Erkin-Cakmak are analyzing CHAMACOS data to investigate links between early-life exposure to persistent organic pollutants, including organochlorine pesticides, and cardiometabolic disorders such as obesity in young adults from the cohort. They hope to expand their project to examine the association between exposure to currently used pesticides, such as glyphosate and neonicotinoids, and these health outcomes.

From the Clinic to the Bench

Erkin-Cakmak earned her pediatric medicine degree in her native Turkey, before realizing she wanted bench research to be part of her career.

“I wanted to contribute not only to children’s health through care, but also by conducting research to inform the care we provide,” Erkin-Cakmak said.

She started almost from scratch as a master’s student at UC Berkeley, where she became involved in CHAMACOS research. She then trained at UCSF, where she is now a pediatric endocrinologist and researcher.

Mora also transitioned from a clinical medicine career to scientific research. After earning her medical doctorate in Costa Rica, she worked for a year as a primary health care practitioner in the Costa Rican Social Security Health System. She discovered her passion—and a pressing need in her community—to understand the health effects of pesticide exposure in vulnerable populations. Costa Rica is a major banana producer, and many residents are affected by the chemicals that banana growers spray on crops.

“I grew tired of treating people only after they had been diagnosed,” Mora said. “That sparked my interest in identifying and reducing risk factors rather than intervening at the later stages of disease.”

Study Spinoffs Multiply Positive Impacts

The CHAMACOS cohort study has informed many new, related studies, often led by community members whom the study has engaged over the years. One example is the CHAMACOS Youth Council, a group of Salinas youth trained in community-based science. The council has provided research feedback and conducted its own studies.

“These youth were trained to design questionnaires, collect data, and analyze them,” Mora explained. “In some cases, they even met with local decision-makers to discuss the results. It was a very empowering experience for them.”

Young researchers trained through CHAMACOS have examined pesticides' effects on teenage girls living near agricultural operations in the COSECHA study, tracked exposure to hormone disruptors in cosmetics in the HERMOSA study, and shown how to reduce household exposure to carcinogens in cleaning products in the LUCIR study. (Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley)

The ripple effect of the CHAMACOS cohort extends even further. Mora brought her knowledge and experience from the study to her home country of Costa Rica, where she collaborated with Berna van Wendel de Joode at Universidad Nacional to launch a birth cohort study of mother-child pairs living near banana plantations. Now more than ten years old, the study has uncovered significant adverse health effects associated with pesticide exposure.

Erkin-Cakmak spoke of trying to make ripples in her networks back in Turkey.

“I still have conversations with my doctor colleagues who are practicing there,” Erkin-Cakmak said. “I try to communicate what I have been learning about how exposure to pesticides can have lifelong effects on health to my connections there.”

The Power of Personalized Results

Erkin-Cakmak and Mora noted that the CHAMACOS study has always prioritized sharing its findings with the Salinas Valley community. The researchers publish a biannual newsletter called “La Semilla” — Spanish for “the seed” — in which they present complex scientific data in an understandable and relevant way to the community.

Parents and children in the cohort are also invited to an annual community forum, where researchers share individualized study results. Mora has helped host a few of these gatherings, during which CHAMACOS researchers explain to each participant what chemicals they have been exposed to, how their exposures compare to the rest of the study population, and how these exposures may affect their health.

“We are very mindful of the results we share and the purpose behind them,” Mora explained. “We don’t want to scare people, but to provide guidance on how they can potentially reduce their exposures.”

For example, Mora pointed out, that the participating parents cannot change their past exposure to organochlorine pesticides, but they can reduce their own and their family’s contact with current-use pesticides, flame retardants, and forever chemicals.

“I have found people are interested in learning no matter where you are, whether in a meeting [with peers] or when you visit a Salinas clinic and meet with study participants,” Mora noted. “People want to learn how they can improve their health. Once you have given them the information, you’ve put power into their hands.”

Liliana Aguayo, Ph.D. – Helping Families Make Heart-Healthy Choices

March 5, 2025

The culture, relationships, and behaviors that make up a person’s social circle are not always top of mind for environmental health researchers, who often focus on chemical exposures. But Liliana Aguayo, Ph.D., a research assistant professor in the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing at Emory University, believes that social factors play a pivotal role in health outcomes, especially for children.

With this in mind, Aguayo, a scholar in the NIEHS-funded Pediatric and Reproductive Environmental Health Southeastern Environmental Exposures and Disparities (PREHS-SEED) program, uses qualitative and quantitative approaches to study the origins of cardiovascular health disparities in children.

“There is no one-size-fits-all answer when it comes to better health outcomes for children,” said Aguayo. “For each child, we need to determine the unique factors within their own social environments that are contributing to – or protecting them from – the development of disease.”

Early Influences

Aguayo’s commitment to studying social factors formed at a young age. Her family frequently visited a small mountain village in Mexico. There, they knew a poor, older woman who had been kicked by her donkey while selling cheese.

Her parents helped the woman get to the hospital where she was treated. In the process, doctors were surprised by her exceptional health. As a woman in her 60s living alone in a rundown shed, they didn’t expect her exam to reveal the health of a 20-year-old.

“We know from the social determinants of health literature that people with a lower socioeconomic status have poorer health compared to those with a higher socioeconomic status,” said Aguayo. “And yet, this lady was so healthy.”

The woman may have benefitted from a healthy diet, strong social network, and daily walking routine, said Aguayo. Her lack of electricity – which could have resulted in an earlier bedtime and more sleep– may have also played a role.

“When I think about my research, I want to disentangle what this lady had been doing since childhood. What can we take from her lifelong experience to make sure that social or economic circumstances don't dictate our destiny in terms of health?” she said.

Getting to the Bottom of Health Differences

Aguayo took a roundabout path to her research position. After receiving a political science degree from Loyola University, she worked as a Spanish translator for a company that administers health-focused questionnaires to families.

There, she witnessed firsthand the role that language and culture play in health evaluation. For example, Spanish-speaking respondents who were asked to order objects by size for a cognition test would often perform poorly on the test. But Aguayo helped her colleagues realize that the word for one of the objects – “elk” – does not translate well into Spanish and is not a familiar concept for most Hispanic families.

Aguayo presented her research at the 2023 Congresso Brasileiro de Nutrilogia in Brazil. (Photo courtesy of Liliana Aguayo.)

Her passion for listening to respondents to understand their unique circumstances and improve health led her to pursue a joint master’s and doctoral degree in public health from the University of Illinois. Afterwards, as a postdoctoral researcher at the American Heart Association and Northwestern University’s Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital, she began to investigate why some children were more prone to poor cardiovascular health than others.

For example, she found that among Black and Hispanic children, those whose mothers had a higher pre-pregnancy body mass index score were at an increased risk of developing obesity in childhood. The finding suggests that interventions aimed at helping mothers achieve a healthy weight before pregnancy may help reduce childhood obesity in these populations.

Serving Communities

As a scholar in the PREHS-SEED program, Aguayo received funding to conduct a large-scale review of studies examining cardiovascular health predictors, outcomes, and mechanisms across the life course. This effort has informed her community-based research aimed at improving child health.

For one project called “Little Hearts,” she partnered with nursing faculty at Universidad Autonoma de San Luis Potosi in Mexico to provide free cardiovascular health assessments to mothers and children through a public kindergarten.

“Many of the mothers haven’t had health care evaluations since their children were born,” said Aguayo. “We identified and referred a few cases of diabetes and high blood pressure for further assessment, evaluated the children's health, and gave the information to the mothers so they can bring it to their pediatricians.”

The team is now using the data to develop an intervention aimed at curbing consumption of added sugars from ultra-processed foods.

Aguayo (left) became involved with the Little Hearts community-based program in Mexico in 2022. (Photo courtesy of Liliana Aguayo)

For another project, Aguayo works with endocrinologists to develop a dietary intervention to prevent metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) among Hispanic children aged 6-9 years in Atlanta. Studies have shown that Hispanic populations have the highest prevalence of MASLD in the U.S. As part of the program, participants and their siblings get access to free cardiovascular and liver health screenings.

Most recently, Aguayo joined an Emory University program that provides health services to farmworker families in Georgia.

“Farmworkers are one of the most vulnerable populations in the U.S., often experiencing dehydration, greater exposure to pesticides, and weather-related injuries,” said Aguayo. “Although they make it possible for us to have fresh foods and vegetables, in many cases they lack access to fresh produce. As a result, they are at greater risk for diabetes, MASLD, and other preventable chronic diseases.”

Aguayo’s long-term goal is to use data from these projects to devise ways to improve heart health. Her participation in the PREHS-SEED program has been paramount to helping her work towards this goal.

“Findings from these different projects and the statistical training and career development support I’ve received have helped me identify key knowledge gaps and how to address them as I move forward in my research career,” she said.