April 18, 2025

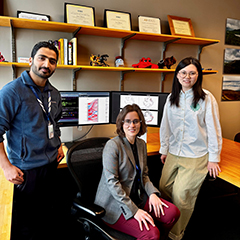

Tanya Alderete is an associate professor in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. (Photo courtesy of Alderete)

Watching her grandmother navigate a heartbreaking cancer diagnosis led Tanya Alderete, Ph.D., to pursue a career in scientific research. Alderete grew up in the rural central valley of California and was the first in her family to attend college. She took pre-med classes and worked as a research assistant while an undergrad at the University of Pennsylvania before ultimately deciding that scientific research was her calling.

“I just assumed that the best way to help people was becoming a medical doctor, but I later learned that you could also do research focused on human health and disease,” she said.

Alderete next earned a doctorate at the University of Southern California (USC), where she researched the pathophysiology of obesity and type 2 diabetes, focusing on diet, physical activity, and fat distribution.

Her interest in environmental health research grew through involvement with the university’s NIEHS-supported Environmental Health Sciences Core Center. The center provided her laboratory resources, weekly career development meetings, and networking opportunities that led to key scientific collaborations.

“As I advanced in my training, I realized that the environment we live in and the exposures we face play an important role in our health,” she said. “Growing up in California's Central Valley, a region known for its high levels of air pollution, further fueled my interest in environmental health sciences.”

Connecting Air Pollution, the Gut, and Diabetes

Research mentors during her time at USC helped Alderete, pictured here in 2010, understand the importance of persistence, critical thinking, and strategic decision-making in science. (Photo courtesy of Alderete).

While completing her postdoc at USC, Alderete worked with environmental epidemiologist Frank Gilliland, M.D., Ph.D. They found that children exposed to air pollution had reduced insulin sensitivity and dysfunction of the cells that produce insulin.

The study provided new evidence that air pollution exposure may contribute to the biological processes underlying type 2 diabetes. This finding fueled Alderete’s growing suspicion that the gut microbiome plays an important role at the interface between human health and the environment.

“At the time, I was closely following the emergence of microbiome research and was fascinated by its potential to bridge gaps in our understanding of how the environment affects health,” said Alderete. “I wanted to integrate microbiome science into my work, as it represented a powerful, yet largely unexplored, pathway through which pollutants could impact metabolic and immune function.”

She explored that idea further with the support of a Pathway to Independence Award from NIEHS, which was a launching pad for her career. Alderete’s team found that exposure to traffic-related air pollution negatively affected metabolic health in young adults by altering the gut microbiome.

“To my knowledge, our studies were the first to demonstrate a link between air pollution exposure and the gut microbiome,” said Alderete.

Focusing on Early Life Environmental Exposures

In 2018, Alderete accepted a position as assistant professor at the University of Colorado Boulder.

While there, her group produced the first evidence of significant associations between exposure to air pollutants and the compositional and functional profile of the human gut microbiome. She also published a review article summarizing the evidence linking exposure to air pollutants with the gut microbiome and presented her work at a 2021 microbiome workshop sponsored by NIEHS.

Simultaneously, Alderete was working with Michael Goran, Ph.D., at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles to study the effects of air pollution on the overall health of approximately 200 mother-infant pairs from the Southern California Mother's Milk Study.

They found an association between mothers who had high exposures to particulate matter air pollution during mid-to-late pregnancy and lower motor, cognitive, and language scores in their two-year-olds. Additionally, prenatal exposure to air pollution was associated with increased adiposity, or excessive fat, in the first six months of an infant’s life.

“These studies suggest that reducing exposure to air pollution during early life may protect children from a range of negative health outcomes,” said Alderete.

She then received two NIEHS research awards to investigate how early-life environmental exposures shape key developmental processes.

In one project, she is examining how exposure to PFAS through breast milk affects the developing gut microbiome, and whether these changes may influence childhood obesity risk. The team has detected PFAS in breast milk at one and six months postpartum and are seeing early evidence that the pollutants influence the infant microbiome, which could have downstream effects of metabolic and immune development.

Alderete points out that while breast milk can contain PFAS, breast feeding still offers numerous benefits for infants, including supporting gut microbiome development, bolstering the immune system, and aiding neurodevelopment.

“Parents can take steps to limit PFAS exposure — such as using filters certified to remove PFAS from drinking water, avoiding non-stick cookware, and reducing consumption of processed foods,” she said.

Alderete is also examining how early life air pollution exposure influences child neurodevelopmental outcomes.

“By identifying key microbial and metabolic pathways disrupted by air pollution, we can improve our understanding of how environmental exposures contribute to cognitive and behavioral development,” said Alderete.

Alderete (center) and postdoctoral research scholars Devendra Paudel, Ph.D. (left), and Haonan Li, Ph.D. (right), explore the links between environmental exposures — such as air pollution and PFAS — and the infant gut microbiome. (Photo courtesy of Adrianna Luger / Johns Hopkins University)

Forming New Collaborations

Alderete’s move to Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health in 2024 has provided opportunities for her to inform public health practice. She is also exploring the links between PFAS and cancer.

“So many of us have been touched by cancer — whether personally or through loved ones. It’s very rewarding for me to be contributing to this area of research,” she said.

Alderete says her biggest motivation comes from knowing that her research has the potential to inform interventions and clinical guidelines that improve health outcomes.

“Seeing my research findings contribute to broader public health efforts is what makes this work so rewarding."