Features

Promoting Healthy Fish Consumption

Many fish species can absorb contaminants from water, sediments, and the food they eat. Eating fish from contaminated areas may expose humans to substances that can harm their health. Funded by SRP, researchers across the U.S. are working to understand the many sources of pollution exposure and identify solutions to protect public health. Scientists are also teaming up with residents to create community-engaged research projects that address fish consumers’ concerns, and then communicate their findings and recommendations in ways that speak to the culture of each community.

Documenting Metal Exposures

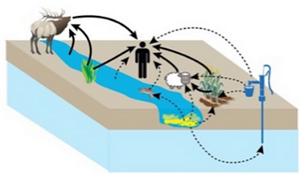

This graphic shows the different ways that Navajo Nation members can be exposed to contaminants in the San Juan River. (Image adapted from Ornelas Van Horne et al., 2023)

In response to the 2015 Gold King Mine spill that impacted the Navajo Nation, the University of Arizona SRP Center conducted a health risk assessment to document exposure to contaminants. The spill contaminated the San Juan River — which flows through the Navajo Nation and is used for several recreational, cultural, and dietary activities — with arsenic and lead. Researchers found that risks from recreational and cultural uses of the river were not statistically significant exposure pathways, but consuming fish from the river resulted in significant cancer risk related to arsenic exposure. To communicate their results, the team launched a report-back plan that included print materials and videos in Navajo and hosted community meetings in Navajo chapter houses.

Researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health SRP Center found sociodemographic disparities in mercury exposure from fish consumption near coal-fired power plants. In the environment, mercury is converted into methylmercury, which has been linked to impaired brain development in children and cardiovascular disease in adults. The team found that low-income individuals living within five kilometers of coal-fired power plants and people who frequently consume self-caught fish were at the highest risk of methylmercury exposure.

Northeastern University SRP Center scientists analyzed metal exposures among pregnant women in Puerto Rico and collected a questionnaire on their lifestyle and food consumption. They found that women who consumed fish were more likely to have biomarkers of arsenic and mercury exposure. The team is using this data to inform future epidemiology studies and exposure reduction strategies.

Analyzing PFAS in Seafood

URI SRP Center members use a seine net to collect fish from Moody Pond, New York. (Photo courtesy of URI)

The University of Rhode Island SRP Center is characterizing PFAS accumulation in the aquatic food web to support risk assessments and fish consumption advisories. The team is collaborating with the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe on Cape Cod, Massachusetts to develop identity-based messaging strategies to communicate PFAS risks with Tribal members and evaluate the effectiveness of various messages and delivery channels to reduce PFAS exposure.

Celia Chen, Ph.D., and Megan Romano, Ph.D., from Dartmouth College, received an SRP time-sensitive research grant to monitor PFAS in marine fish and shellfish. Chen and Romano collected and analyzed samples from seafood caught from the Gulf of Maine and the Great Bay. Additionally, the research team conducted a survey of seafood consumption in New Hampshire and tested PFAS concentrations in the most frequently consumed seafood.

Chen and Romano found that razor clams and skates in the Gulf of Maine contained levels of PFAS exceeding screening levels for adults and children. Long-chain PFAS, which are compounds with many carbon atoms, were the most common type of PFAS found in seafood. The researchers’ seafood survey also revealed that seafood consumption among adults in New Hampshire is higher than levels estimated for the Northeastern U.S. Of the most frequently consumed seafood, shrimp and lobsters had PFAS concentrations that could negatively affect human health. According to Chen and Romano, their data may help inform public health policies surrounding seafood consumption in the Gulf of Maine region.

The North Carolina State University (NCSU) SRP Center investigates how PFAS bioaccumulate in all levels of the food web, how toxic different pathways of exposure to PFAS can be, and how present and persistent PFAS are in watersheds. For example, researchers found higher levels and more types of PFAS in fish fillets from fish near known PFAS point-sources in the Cape Fear River watershed.

Improving Fish Consumption Advisories

Fish consumption advisories aim to help people make informed decisions about whether to eat, avoid, or limit the consumption of certain fish or shellfish caught in specific bodies of water. SRP-funded scientists are working closely with communities at risk of consuming contaminated fish to inform new advisories and improve how recommendations are communicated.

The color-coded map of fishing sites which corresponds to specific fish advisories in those areas; this resource is from 2016 and information may not be current. (Photo courtesy of UNC SRP)

Researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) SRP Center conducted focus groups to understand how to better communicate fish consumption advisories. Results of the focus group led the team to recommend streamlining messaging and using visuals. They also developed outreach materials, like the Eat Fish, Choose Wisely guide, which included a color-coded map for people to identify areas where they can catch fish that are safer to eat. This work was previously funded by SRP and now continues with funding through the NIEHS Environmental Health Sciences Core Centers Program.

Duke University SRP Center scientists and collaborators tested the most consumed fish along the lower Cape Fear River, a watershed contaminated with industrial contaminants, and found that frequently consumed fish had high levels of mercury, hexavalent chromium, and arsenic. This data was then used by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services to develop new fish consumption advisories and inform the public of the risks of eating certain fish.

Image of the attendees at the Go Fish Fest! event. (Photo courtesy of Duke SRP)

The Community Engagement Core at the Duke SRP Center also released a manual for helping local health departments and communities collect and test fish samples to inform fish advisories. Members of the CEC developed the Stop, Check, Enjoy! Campaign to inform the public about the health risks of eating contaminated fish and to provide methods for preparing fish to limit exposure to contaminants. The team partnered with local organizations to host outreach events and produce a short comic book aimed at promoting safe fish consumption in the region. They also created a social media toolkit with educational brochures, videos, and recipe calendars.

The Duke team also collaborated with the NCSU SRP Center to release a manual for developing and communicating fish consumption advisories. The manual addresses the current shortcomings of fish advisories and includes best communication practices and strategies for engaging with hard-to-reach communities.

In 2019, the Fish Forum worked with a visual note-taker who helped capture a visual summary of the key points and discussion. (Photo courtesy of Duke SRP)

In 2019, the SRP Centers at Duke University, UNC, and NCSU collaborated to host the North Carolina Fish Forum. The goal of the forum was to better understand the process of setting fish consumption advisories and barriers to more effectively communicating them. Following the forum, the group released a white paper highlighting key challenges, next steps, and future opportunities to improve the efficacy of fish consumption advisories. The collaborating centers hosted another forum in 2023, focused on PFAS contamination in fish.

Reducing PCB Uptake by Fish

Ghosh, right, and colleagues collect samples to measure PCBs. (Image from a YouTube video highlighting work in Delaware)

Upal Ghosh, Ph.D., of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and collaborators developed specialized pellets of activated carbon that absorb polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in aquatic environments. The technology, called SediMite, can reduce the uptake of PCBs by fish and other aquatic organisms.

Ghosh and his team collaborated with the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control to use SediMite at Mirror Lake. Between 2013 and 2018, the researchers found that PCB concentrations in the sediment porewater, or the water between sediment grains, decreased by 80%, while PCB levels in the lake’s fish decreased by 70%.

In 2020, the team received an SRP small business grant to address current limitations to SediMite, including improving the growth and storage of large volumes of PCB-degrading microorganisms.

to Top