Features

Work with Native American Communities

Native American communities across the U.S. experience disproportionate exposure to hazardous chemicals, compared to the rest of the population. Active and legacy mining and waste-storage operations may expose some of these communities to chemicals that can persist in the environment and affect health.

Funded by SRP, researchers across the country are working to understand the many potential sources of exposure and identify solutions to protect health in Native American communities. Scientists and community outreach experts are teaming to create community-engaged research projects that address concerns, then communicate their findings and recommendations in ways that speak to the culture of each community.

Cleaning up Drinking Water Sources

Native Americans in the U.S. Northern Plains are exposed to high levels of arsenic, uranium, and other metals in their drinking water. In 2022, Columbia University and Tribal partners in the Northern Plains founded the Columbia University Northern Plains (CUNP) SRP Center to address this contamination. All of the center's research projects and interventions have been identified, co-designed, and are being led in collaboration with Tribal partners, such as Missouri Breaks Inc., a Native American-owned research organization.

Using data from the Strong Heart Study, the researchers are revealing the adverse health effects of metal exposures, including insulin resistance , diabetes , lung disease , and cardiovasvular disorders . The Strong Heart Study is the largest and longest prospective study in Native American communities.

Because many Tribal communities are dependent on private wells and rural water systems, CUNP SRP Center investigators are modeling groundwater metals concentrations to identify where mitigation strategies are needed, locating sources of metals contamination, and developing interventions to prevent exposures. Recently, the team worked with their Tribal partners to launch an intervention that combines an arsenic filtration system under the kitchen sinks in community members' homes with an education component to reduce exposure to arsenic.

Addressing Contamination Near Abandoned Mines

More than 600,000 Native Americans in the southwestern U.S. are estimatedto live within about six miles of an abandoned mining site. In response to concerns from Tribal members, the University of New Mexico (UNM) SRP Center addresses legacy contamination from abandoned uranium mines on Navajo Nation and Laguna Pueblo land. UNM SRP Center scientists study mining waste that includes complex mixtures of metals, such as uranium, arsenic, and lead.

Researchers at the center seek to understand how exposures to metal mixtures may harm health, such as their potential toxicity to the respiratory and immune systems of Tribal community members. The center's community-partnership approach includes Tribal partners as integral members of the research process, which allows center investigators to design and conduct research that is scientifically sound and respectful of culture. The team is also working with Tribal partners to develop a strategy that uses plants and fungi to remove metals from soil.

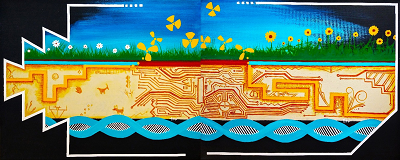

Drinking water contaminated with metals is also a major problem in Native American communities, as many residents rely on unregulated private wells or rural water systems. The UNM SRP Center, in collaboration with federal agencies and Tribal colleges, created Navajo WaterGIS , an online mapping tool that allows Navajo members to visualize water quality in their area. The map includes measures for arsenic, uranium, radon, and calcium. Center researchers also collaborate with Research Translation Coordinator Mallery Quetawki to communicate their findings and environmental health concepts in a culturally appropriate way, using Tribal symbolism and traditional knowledge.

Another group, at the University of Arizona SRP Center is studying how exposure to metals, from natural geology as well as abandoned mining sites, affects the health of Native American communities in the Southwest, making them more vulnerable to diseases like diabetes.

The center's Community Engagement Core (CEC) focuses on engaging affected Tribal members to reduce exposure through learning modules, outreach, workshops, and community-engaged participatory research. This work is possible thanks to strong and lasting partnerships with Native American communities, Tribal leaders, and Tribal colleges. One of their projects, Indige-FEWSS (for Indigenous Food, Energy, and Water Security and Sovereignty) aims to engage Native American students in the development of new, sustainable solutions for off-grid production of safe drinking water, brine management operations, and controlled-environment agriculture systems. Another project, Farming is Life , supports Navajo farmers as they monitor their crops, soil, and water for metals, including arsenic and lead.

Communicating science and research results in culturally appropriate and respectful ways is another priority of the center. In response to the 2015 Gold King Mine spill in the southwestern U.S., center researchers mobilized teams to the area to assess the extent of contamination and track exposures over time. Following the risk assessment process, they launched a report-back plan that included print materials and videos in Navajo and hosted community meetings in Navajo chapter houses.

Protecting Native American Communities in Maine

Worried about harmful exposures from contamination in the Loring Airforce Base Superfund site in Maine, Native American communities living near the site reached out to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) SRP Center for help. Led by Kathleen Vandiver, Ph.D., the CEC at the MIT SRP Center analyzes exposure to N-nitrosamines and potential health effects among the Passamaquoddy Tribe, one of four tribes comprising the Wabanaki Indians. N-nitrosamines are a group of chemicals suspected of causing cancer and have been found in the Tribe's water supply. Collaborating with environmental officers and educators working with five Wabanaki communities, the MIT SRP Center shares their research findings with residents.

Vandiver and team also educate Wabanaki Tribal youth by collaborating with cultural knowledge sharers, known as Culture Keepers, through a program called Wabanaki Youth in Science . The program provides experiential learning opportunities for Indigenous youth such as through hands-on learning kits used to teach key concepts of biology and environmental health.

Also in Maine, researchers funded by an SRP individual research grant are collaborating with the Mi'kmaq Nation, another Wabanaki community near the Loring Airforce Base Superfund site, to use plants to remove PFAS from land owned by the Tribe. The group, led by scientists at Yale University and the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, has been working with Tribal leaders to measure PFAS levels on their land and are now testing their remediation technology on Mi'kmaq soil samples.

Communicating Health Risks

The University of Rhode Island (URI) SRP Center CEC partners with the Mashpee-Wampanoag Tribe to evaluate PFAS exposure among tribal members and develop culturally specific risk-reduction strategies. The CEC collaborates with the Tribe to collect fish, shellfish, and well water samples for PFAS analysis to assess risks. Additionally, they work with Tribal members to develop identity-based messaging strategies to communicate PFAS risks and evaluate the effectiveness of various messages.

The team also collaborates with the Mashpee-Wampanoag Tribe for their annual Preserving Our Homeland Tribal Youth camp, a hands-on science program for Native students. In 2023, URI SRP Center trainees and CEC staff led a half-day of the camp to introduce campers to PFAS and other chemicals in their environment. The team led hands-on activities introducing campers to different aspects of PFAS, including demonstrating a passive sampler, having the campers act out how PFAS accumulates through the body and the food webs, and how laboratory techniques can be used in PFAS analysis.

The CEC at the Duke University SRP Center works with the Waccamaw Siouan Tribe in southeastern North Carolina to conduct environmental sampling within the community. In partnership with Eric Britt Moore, Ph.D., a soil scientist at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, Duke CEC is helping Tribal representatives contextualize results about chemical contaminants in their soil and drinking water.

In April 2023, Duke CEC sponsored and attended the Tribe's third annual Yacunne Fish Camp in Bolton, North Carolina. The event, which included representatives from seven other Tribal groups, was a chance for the community to gather and share stories while fishing.

Promoting Health in the Pacific Northwest

Researchers at the Oregon State University (OSU) SRP Center identify public health interventions and prevention strategies to protect Pacific Northwest Tribes from exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and other harmful substances. Center researchers use tribal land-use scenarios and model unique exposure pathways to ensure their risk reduction strategies will improve Tribal health.

For their research, center scientists regularly collaborate with local Indigenous communities. For example, the researchers partnered with the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community and the Samish Indian Nation to collect butter clams and place passive samplers in sediment to measure environmental contamination. In another study, a team worked with the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation to study exposure to PAHs through consumption of smoked salmon .

Working closely with their Indigenous partners, the CEC at the OSU SRP Center aims to build scientific and cultural capacity in Tribal communities. One of their activities is the Sense of Place seminar series, a collaboration with the Indigenous Education Institute that highlights Tribal speakers in the Pacific Northwest. The seminars discuss impacts of pollution on tribal sovereignty, Indigenous health, and First Foods - traditional Native American cultural foods. Additionally, the CEC hosts annual Tribal Youth Tours , which connect tribal students with environmental health research at OSU.

The CEC also led an Environmental Health Photovoice activity with the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community. Tribal members submitted photographs that showed climate change along with a short explanation of what the picture meant to them, which were then compiled into a Swinomish news publication . This method can help increase community engagement with environmental health and health concerns, says the team.

to Top