- Kathleen Vandiver, Ph.D. – Building Environmental Health Literacy Across Generations and Communities

- Max Aung, Ph.D. – Tackling Environmental Exposures in Communities

- Jennifer Richmond-Bryant, Ph.D. – Combining Environmental and Social Sciences to Address Community Air Quality Concerns

- Kelly Pennell, Ph.D. – From Pipes to People: Addressing Vapor Intrusion and Water Contamination

- Denae King, Ph.D. – Joining Forces with Communities to Address Health Disparities

- Allison Patton, Ph.D. – Modeling Traffic-related Pollution, Promoting Health

- Linda McCauley, Ph.D., R.N. – Integrating Nursing and Environmental Research to Promote Community Health

- Mallery Quetawki – Using Art to Improve Environmental Health Literacy Among Indigenous Tribes

- Kevin Lane, Ph.D. – Applying Spatial Analysis to Air Pollution Research

- Joseph Hamm, Ph.D. – Fostering Trust-Building to Promote Environmental Health

Kathleen Vandiver, Ph.D. – Building Environmental Health Literacy Across Generations and Communities

December 8, 2023

The educational models that Vandiver created as a teacher have helped her translate environmental health science to a number of communities and age groups. (Photo courtesy of Kathy Vandiver)

Prior to joining the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2005 as a community engagement and education specialist, Kathleen Vandiver, Ph.D., taught middle school science for 16 years. During that time in the classroom, she relished devising experiments and hands-on activities to help her students recognize and experience key scientific concepts.

Vandiver’s work illustrates the value of developing teaching tools that can accommodate learners at different educational levels — a practice known as universal design. For example, DNA models she created are marked with large arrows and chemistry symbols to help students remember how the molecule assembles.

“Middle school is when most kids decide what subjects they like,” said Vandiver. “Engaging them with materials in a way that is most beneficial for their learning also helps foster an interest in science. I later realized I could reach out to the public with a similar approach from MIT.”

Vandiver has since dedicated her career to teaching environmental health concepts to students, Tribal populations, health professionals, and communities affected by environmental contamination.

Reporting Back on the Malden River

Years ago, as Director of Community Outreach and Education at MIT’s Center for Environmental Health Sciences, which receives funding through the NIEHS Core Centers program, Vandiver saw a public health need in Malden, Massachusetts, a city north of Boston.

“Public officials in Malden were worried about the Malden River, and with good reason,” she said. “Throughout the 20th century, industries such as rubber, iron, and munitions manufacturers dumped their wastes — with the potential for producing serious health effects — into the river. In particular, parents of Malden’s high school rowing team were very concerned about the youth who practiced daily on this river.”

Vandiver recognized that a human health risk study was necessary before the river could be considered a safe place for boating. She put together a team, including an expert from an environmental firm, a local watershed association, and an MIT toxicologist, to gather data.

The team collected sediment samples from boat launch locations, analyzed their contaminant levels, and calculated the health risks faced by boaters who might have contact with the water and sediments. Fortunately, they found a negligible risk of cancer for recreational boating.

“In the absence of a rigorous health risk analysis, ‘stay away from the water’ has been the logical precautionary advice given to the public in prior years,” Vandiver said. “Now, we explained that just because a toxicant is present does not necessarily mean community members are at risk of health effects.”

According to Vandiver, the study results supported the Malden River as a public amenity. Subsequently, the mayor and city councilors endorsed a proposal for a public park project led by Vandiver, called Malden River Works, which won a Leventhal Cities Prize for innovative urban design.

After several years of community participation and engagement, the park plan is now in place, including environmental restorations, pathways along the river, and a boathouse with a dock for public boating. Construction will begin in 2024.

Guiding Community Cleanup

Vandiver’s MIT work also includes leading community engagement efforts for the NIEHS-funded MIT Superfund Research Program. In that role, she is involved with the Wilmington, Massachusetts, community to address concerns related to exposure to N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a potentially cancer-causing chemical. Ineffective containment of millions of gallons of hazardous waste at the Olin Chemical Superfund site has led to NDMA contamination in Wilmington groundwater.

In collaboration with the University of Cincinnati and the University of Pennsylvania, Vandiver led MIT’s efforts to create Lessons Learned on the Road to Environmental Cleanup, an online resource with educational and interactive modules, short videos, and questions for reflection to help participants address chemical exposures in their communities.

To create this online resource, Vandiver conducted interviews with Wilmington residents, guiding them to share words of advice about their experiences dealing with chemical exposures. For example, to form an effective community organization, residents suggested electing a board, identifying core values, and creating simple bylaws and goals. They also explained how community organizations can apply for financial support to hire technical professionals to assist in gathering additional data.

“Our hope is that the modules will help new groups learn how to navigate environmental cleanups,” Vandiver said. “The tool is unique because it supports not only community members but also provides useful information for all individuals who are involved in cleanups, including government officials, workers on the job, and company representatives.”

Abby Harvey (left) and Tchelet Segev (right) — MIT graduate students mentored by Vandiver — tested water samples for metals in this citizen scientist project with the Passamaquoddy Tribe. (Photo courtesy of Kathy Vandiver)

Partnering With the Passamaquoddy

Over the years, the Center for Environmental Health Sciences and the MIT Superfund Research Program have partnered with the Passamaquoddy Tribe in Maine to address their environmental health concerns related to heavy metals in drinking water.

Vandiver prioritizes ongoing engagement with Tribal colleagues, which starts before any research study is proposed and continues with regular visits over the long term. In one participatory science project, she partnered with the Tribe’s Environmental Department to assess water quality in Passamaquoddy households and create individualized reports. Aggregated responses were presented at community meetings, along with a sample report to show how to interpret the numbers.

“Community members were actively involved in the sample collection and research process, which helped them learn about safe contamination levels and potential health effects,” Vandiver said.

She continues to work with the Tribal Environmental Department and MIT researchers to collect samples and help protect the community.

Modeling Air Molecules

Ever the teacher, Vandiver also continues nurturing the next generation of scientists.

For example, Vandiver designed custom LEGO brick sets to introduce children to the molecules found in air pollution. These hands-on tools make difficult concepts tangible, allowing kids to manipulate the bricks as if they were atoms.

Vandiver’s peers have long taken note of her dedication to educating children. In 2011, she was inducted into the Massachusetts Hall of Fame for Science Educators for her efforts to make abstract concepts clear to teachers, students, and community members alike.

Vandiver hopes to introduce more environmental health education tools into as many classrooms as possible, and to provide teachers with online support for their use.

“Teachers might teach thousands of students throughout their careers, creating a huge multiplier effect to improve environmental health literacy,” she said.

Max Aung, Ph.D. – Tackling Environmental Exposures in Communities

November 14, 2023

(Photo courtesy of USC)

When Max Aung, Ph.D., was an undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Cruz, he was studying molecular biology. A pivotal experience in his junior year guided his path. He participated in a summer program at Stanford University focused on providing public health and medical training experiences for first-generation college students.

“I had the opportunity to learn from leading physicians and public health practitioners. As a first-generation college student, that exposure motivated me to continue being a strong basic scientist while also pushing research forward,” he explained.

Now an assistant professor at the University of Southern California (USC), Aung conducts research focusing on maternal and child health. He is an integral member of the NIEHS-funded USC Environmental Health Sciences Center and the MADRES Center for Environmental Health Disparities. The MADRES Center is supported by NIEHS, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Interdisciplinary Science and Research Translation

Aung’s interest in investigating the effects of hazardous exposures on maternal health and infant development in part stemmed from his involvement with the NIEHS Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center at Northeastern University while pursuing a doctoral degree at the University of Michigan. There, he collaborated with engineers, toxicologists, and other experts to understand the link between environmental contaminants and adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as preterm birth, in Puerto Rico.

“My experience with SRP inspired me to think about how multidisciplinary methods can be used to translate science so that decision makers and community members can use it to inform interventions and policies,” Aung said.

At USC, Aung leads a translational environmental health research laboratory. One of his research domains involves conducting multidisciplinary science to reveal how exposures in utero affect children’s neurodevelopment.

For example, he collaborated on a MADRES study that found prenatal exposure to the flame retardants organophosphate esters was associated with adverse neurobehavioral outcomes, as reported by low-income Latina mothers in children 3 years old. Findings like this one can influence health-protective decisions and policies down the road, according to Aung.

Detection Methods and Policies to Protect Health

“A really important piece of my work is trying to devise strategies to prevent further environmental health disparities by addressing exposures early in life and mitigating them as much as possible,” Aung said.

Aung has previously led work to detect biomarkers that predict adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as spontaneous preterm birth. His team’s goal is to translate these findings into clinical tools that allow for early interventions.

“Ideally, we could measure biomarkers early in pregnancy to know an individual’s risk of an adverse outcome and develop interventions to lower that risk,” he said.

Mentoring the Next Generation

(Photo courtesy of USC)

Strong mentorship guided Aung through the early stages of his career. His mentors connected him to opportunities across disciplines and institutions, exposing him to diverse collaborations and ways of thinking.

Now, as a mentor, Aung aims to pay that counsel forward through student mentorship.

For example, Aung participate in a programs that provide early-career scientists with training in storytelling, science communication, and research translation.

“Once you bring students into academic spaces, you need to support them in meaningful, sustained ways so they don’t exit the pipeline,” Aung explained.

Jennifer Richmond-Bryant, Ph.D. – Combining Environmental and Social Sciences to Address Community Air Quality Concerns

October 26, 2023

While Jennifer Richmond-Bryant, Ph.D., was studying for a degree in civil and environmental engineering at Cornell University, she heard that workers in nearby municipal offices were experiencing “sick building syndrome.” This condition occurs when acute health problems coincide with time spent in a building. In such cases, exposure to environmental contaminants may be the cause.

“That got me more interested in pursuing an environmental health angle, because it highlighted that environmental issues are really health issues,” Richmond-Bryant recalled. “I ended up doing my master’s in industrial hygiene. For my Ph.D., I studied the fluid mechanics of environmental transport, which is how fluids influence the movement of particles and pollutants.”

After completing her Ph.D., Richmond-Bryant worked as a contractor for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), researching how people encounter environmental contaminants. She previously studied the transport and dispersion of traffic-related pollution in New York City. After leaving the EPA, she became a professor at City University of New York and examined New York neighborhoods with high asthma diagnoses to deduce if pollution was correlated with asthma cases.

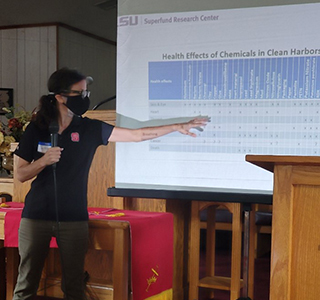

Richmond-Bryant is now an associate professor of geospatial analytics at North Carolina State University. She is also an investigator with the NIEHS-funded Louisiana State University (LSU) Superfund Research Program (SRP), where she studies the effects of air quality on health, and a co-investigator for the center’s Community Engagement Core.

Burning Questions in Colfax

Richmond-Bryant’s research sprang from community concerns in Colfax, Louisiana, where a thermal waste treatment plant releases combustion byproducts into the air. The contaminants include environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs) – highly reactive particles that remain stable for long periods and that have been implicated in heart and lung problems.

In 2010, the waste plant ramped up operations. Shortly thereafter, residents began reporting adverse health effects, such as cardiovascular issues, stomach cancers, and thyroid disease. A coalition of Colfax residents reached out to LSU, asking for researchers to investigate.

Richmond-Bryant and her team are now studying air pollutant levels in the area that may be contributing to the residents’ health problems. In March 2023, they completed a year-long data collection effort, and are in the initial stages of analyzing their findings.

“We’re still working through the results, but we did find levels of EPFRs that were higher than the norm, even for an urban area. This was alongside other contaminants like dioxins and metals, all substances that have been linked to health effects in humans,” she said.

The team shared their results with the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) this past June, just after the thermal treatment plant applied for license renewal. After seeing the preliminary data, the Louisiana DEQ prohibited open burning at the site.

“Seeing our work actually help people is a great feeling,” said Richmond-Bryant. “That’s when you feel like you’ve been doing good work.”

At the community’s request, her team will continue monitoring air quality at the site. According to Richmond-Bryant, although open burning is now prohibited, Colfax residents still worry that closed burning at the site will have negative effects on the community.

“Continued monitoring will allow us to see how things are changing, if there are improvements, or if other contaminants are introduced,” she said.

Collecting Oral Histories

Engagement with Colfax community members is a critical part of this SRP project and has provided important data. For example, Richmond-Bryant’s team collected oral histories from the members of the Colfax community about their own health experiences to map the historical effects of the waste plant.

According to Richmond-Bryant, health statistics in small, rural towns like Colfax can be incomplete because fewer people seek medical assistance, which makes quantitative measures like hospital admissions less reliable. To supplement the limited data, her team spoke with residents, both in-person and by phone about their health.

“We wanted to learn about the residents’ experiences over time, how their health changed and how their community changed,” said Richmond-Bryant. “These oral histories bring out health issues that we wouldn’t have seen if we only looked at the numbers.”

These oral histories highlighted concerns of Colfax residents. According to Richmond-Bryant, the Colfax community has historically been excluded from decisions about the thermal treatment plant.

“Nobody asked the Colfax community when the plant was built. For a long time, community members didn’t have a voice in how the plant operated,” she said. “We wouldn’t have known about these issues if we didn’t do these oral histories and listen to residents.”

For Richmond-Bryant, listening and responding to people is essential to research.

“The most valuable work I’ve done is in response to what I learned from community members. If your work isn’t consistent with what the community is experiencing, then it doesn’t make sense to pursue,” she said. “It’s our responsibility to support the communities that let us in and allowed us to collect data. Their observations are paramount.”

Kelly Pennell, Ph.D. – From Pipes to People: Addressing Vapor Intrusion and Water Contamination

August 31, 2023

(Photo courtesy of Kelly Pennell)

As a high schooler, Kelly Pennell, Ph.D., learned about a Nigerian environmental and human rights activist named Ken Saro-Wiwa, who railed against the oil industry for inflicting decades of pollution on Ogoni communities of the Niger Delta. The devastation endured by Saro-Wiwa’s people haunted Pennell, and she pledged to one day help others affected by environmental exposures.

“I pursued engineering degrees at Lawrence Technological University, Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, and Purdue,” Pennell said. “During that time, I realized how truly complex issues of environmental contamination and remediation are.”

During her Ph.D. work at Purdue, Pennell had the opportunity to work at a NASA Specialized Center of Research and Training, where students developed tools to support astronauts during long-term space missions.

“I worked on a closed-loop, water disinfection system and learned so much about multidisciplinary research,” Pennell said.

Pennell now oversees multidisciplinary work in her role as director of the long-running University of Kentucky (UK) Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center, which combines innovations in biomedicine, environmental science and engineering, and data science with expertise in community engagement and research translation to improve public health and promote health. The center currently focuses on ways to alleviate exposures to PFAS and halogenated organic chemicals — including trichloroethylene (TCE) and tetrachloroethene (PCE) — among other toxic substances.

Tracking Chemicals

Within the center, Pennell is also principal investigator of a project examining how chemicals travel from one place to another — a field called fate and transport. One focus is on vapor intrusion, or the movement of gas-forming chemicals into homes and other buildings from contaminated groundwater and soil.

In early work funded by NIEHS, Pennell and colleagues investigated how to improve vapor intrusion assessments. Working with a neighborhood located adjacent to a former chemical handling facility, the team investigated how predictions from a well-established vapor intrusion model compared to field data collected from the area. Their results were intriguing, Pennell recalled.

“Field sampling revealed that sewer gas containing tetrachloroethylene was escaping into indoor air through a faulty seal at the toilet,” she explained. “Prior to this discovery, vapor intrusion models did not account for sewer gas intrusion as an important pathway.”

In fact, sewer gas has plenty of opportunities to move indoors, according to Pennell. In the U.S., over a million miles of sewer pipes exist underground. As aging pipes deteriorate, surrounding contaminants can migrate in and out, spreading to nearby communities. For example, Pennell and team found that a sewer system installed in the 1950s was the culprit behind TCE infiltration at various locations in a San Francisco Bay neighborhood.

Pennell’s team continues to develop ways to measure and predict chemical intrusion from leaking and damaged pipes, with the goal of reducing exposures. In addition to TCE and PCE, they are also examining PFAS.

Combining modeling, PFAS sampling, and extensive publicly available water data, the team developed a diagnostic tool to visualize potential PFAS hot spots in Kentucky. They also published a companion paper to encourage open data sharing among researchers.

“We aim to conduct the best science that is relevant, credible, and moves knowledge forward,” Pennell said. “Science is a process, and if we don’t keep growing, we don’t innovate, and we stagnate,” she said.

Gathering Feedback

(Photo courtesy of UK SRP)

Critical to Pennell’s job is ensuring that her team seeks — and responds to — community concerns. In 2016, for instance, the center hosted an NIEHS-sponsored community forum for people living in Eastern Kentucky, a geographically isolated region that experiences high rates of poverty, low levels of education and health literacy, limited access to grocery stores, and scant opportunities for exercise.

During the two-hour forum — the culmination of a year of planning with community leaders — audience members queried a panel of experts consisting of local health officials, a nutrition expert, and a federal scientist. Twenty participants also answered an anonymous 10-page questionnaire before leaving the forum. In 2018, Pennell and colleagues reported their findings.

“The most common concerns shared during the forum were about chronic diseases and environmental pollutants, particularly in air and water” Pennell said. “The questionnaire also indicated that this Appalachian community is highly aware of environmental hazards and their health risks. On a positive note, the forum indicated that our center is equipped to respond to the complex needs of these communities.”

Building on the forum, Pennell and several colleagues partnered with local community members on an NIEHS-funded community-engaged project to reduce exposures to disinfection byproducts in drinking water in Eastern Kentucky. The team hopes their work can inform strategies to assist other rural communities facing similar drinking water challenges.

Handling Uncertainty

When Pennell became center director in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic tested her team’s mettle.

“During the height of the crisis, we pivoted,” Pennell said. “It’s one of the accomplishments I’m most proud of.”

With face-to-face community interactions and laboratory research on hold, trainees and faculty sought new projects. For example, Pennell and her collaborators published an article focused on weighing incomplete scientific evidence to inform decisions on the safe reopening of schools.

“These were very heavy lifts, and I will never forget how we made it through and grew during those challenging times. It built resilience and flexibility in us,” Pennell said. “We still had publications coming out, and students staying connected and graduating. And this would not have happened if we did not trust each other and work together.”

Denae King, Ph.D. – Joining Forces with Communities to Address Health Disparities

July 25, 2023

For as long as she can remember, Denae King, Ph.D., has been concerned about environmental health. Growing up in Houston, she had a front-row seat to a car-crushing facility across the street from her grandparents’ home. Watching the heavy machines smash vehicles into metal pancakes, she wondered what kind of contamination might be affecting her neighbors or her family.

Her concerns about industrial pollution only grew after the death of her grandfather, who worked as a pipe fitter on the Houston Ship Channel.

“He would come home wearing company-issued uniforms, take them off outside the house and put them in a bag, and then take them back to work the next day to get the next set of uniforms. Shortly after he retired, he died of a massive heart attack,” King said. “I was 15 at the time and thought that there must be something related to what he did at work that led to him being gone.”

Motivated by those memories, King forged a career in public health. Now an environmental researcher at Texas Southern University in Houston, she works primarily with communities — like the one she grew up in — that are exposed to industrial contaminants.

Building Capacity Within Communities

Among her roles, King is the associate director of the Bullard Center. Also located at Texas Southern University, the center is funded by private and federal institutions, including NIEHS.

“All the work we do is co-led by community members and designed to address community-identified concerns,” King explained. “We educate and train residents, and provide technical and financial support, to build capacity within communities to address those concerns.”

The center has several initiatives related to disaster response. They call it “multi-disaster work,” King noted, because many of the communities they work with are located near industrial facilities and are also vulnerable to natural threats such as hurricanes.

“We work closely with communities to make sure they have a plan when a disaster hits — that includes safe locations to go to, a list of residents to evacuate, and contractors that can go in and do repairs after the disaster,” King explained. “We also recently worked with community leaders to identify designated hubs within communities that have all the supplies a community might need, such as food, personal protective equipment, electricity generators, and tools needed to clear roadways in case of an emergency.”

Job Readiness Training

King is also devoted to raising employment. The Bullard Center provides training to unemployed individuals.

Through a 12-week-long program, the Bullard Center provides rigorous training that prepares participants for work in fields such as environmental cleanup, disaster response, and construction. After the training, staff, Paulette Lynch and Bertina Carter focus on getting participants placed in jobs. The program has a 92% success rate across all their sites.

King said, “We have had participants who were sleeping in their vehicles, people who were living in homeless shelters, or people who were previously incarcerated. And the transformation that you see from the first day to the end of the program, or a couple years later, is extremely rewarding.”

“Once someone is a member of the program, they are always members,” King continued. “If people want to change careers, or if there are changes with their job, they can always come back, and Bullard Center team members will help them find more placements.”

Protecting Black Mothers

Lately, King has incorporated a new focus into her work: maternal health. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Black mothers in the U.S. are three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than White women.

What's driving those disparities is unclear. To explore potential reasons, in 2020, the Baylor College of Medicine and the Bullard Center launched the Maternal and Infant Environmental Health Riskscape Research Center. Co-led by Elaine Symanski, Ph.D., and Robert Bullard, Ph.D., the center is funded by NIEHS, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

“The impact of environmental exposures on maternal and infant mortality is not fully understood,” King said. “This project is helping us understand how some of the contaminants our communities are exposed to, such as lead and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, affect mothers and their babies.”

The center’s research includes participants from the same Houston community where King spent much of her childhood. The area is burdened by legacy contamination sites, King said, and contains a suspected cluster of birth defects and clusters of adult and childhood cancers.

“This work is still in its early stages, but one of our recent accomplishments is that we were able to collaboratively develop a community air monitoring program with our community partner, Coalition of Community Organizations (COCO), and the Environmental Defense Fund,” King said. “COCO purchased low-cost air monitors that measure PM2.5, and we worked collaboratively with COCO’s block captain program to strategically place them in locations across the Fifth Ward community to identify air pollution sources.”

Once they have more data, they’ll be a step closer to understanding local sources of pollutants and how they may impact maternal and infant health.

Allison Patton, Ph.D. – Modeling Traffic-related Pollution, Promoting Health

May 8, 2023

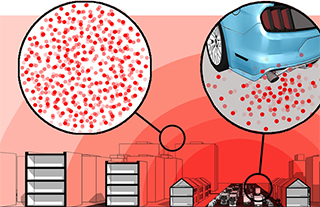

By tracking pollution in the environment, Allison Patton, Ph.D., hopes to improve the health of communities exposed to it.

“Tracking and mapping pollution can help people make the connection between what is in their environment and how they could be exposed,” Patton said.

Patton is particularly passionate about protecting communities from traffic-related air pollution. This interest grew out of her involvement with the Community Assessment of Freeway Exposure and Health Study (CAFEH) while pursuing her doctoral degree at Tufts University. CAFEH is a community-based participatory research project partly funded by NIEHS.

“As I was finishing undergrad and was looking for where to go next, I wanted to make sure that whatever I did made an impact on people’s lives,” Patton said. “I learned about what CAFEH was doing to understand how air pollution affects people’s health, and I knew I had found my next move.”

Now a senior scientist at the Health Effects Institute, Patton oversees studies related to understanding and tracking air pollution emissions from traffic to inform strategies to improve air quality and public health.

Modeling Air Pollution

Patton’s work with CAFEH began during the project’s early stages. The Boston-based team was studying if exposure to the smallest air pollution particles, called ultrafine particles, near highways was associated with cardiovascular disease risk.

“We had a mobile laboratory, and we drove around neighborhoods near Interstate 93 and measured ultrafine particles at different times of the day, across several years,” Patton explained. “Then, we took those measurements, as well as location relative to busy roads, data on wind speed and direction, temperature, and the amount of traffic at a given time, and made models to predict community exposures.”

Notably, the team’s models revealed that air pollution exposure cannot be generalized across neighborhoods, even if they have similar levels of traffic pollution from the nearby highway. Patton noted that factors such as neighborhood elevation, buildings and other structures near the highway, and the placement of roads that lead to highway ramps play a role in the amount of air pollution people are exposed to in different communities.

In response to community concerns about air pollution exposures in the Chinatown area of Boston, which is located near two major highways, Patton helped the CAFEH team create an interactive online tool for health literacy that residents can use to visualize ultrafine particles.

Training in Action

Upon completing her doctoral degree, and with NIEHS support, Patton pursued postdoctoral research training at Rutgers University. There, she looked at differences in air pollution exposure for people driving on the New Jersey Turnpike compared to those driving on local roads.

In 2017, shortly after finishing her postdoctoral work at Rutgers, Patton joined the Health Effects Institute, a nonprofit organization that funds air pollution and health research to inform health-protective policies.

“In my role, I am involved in every step of the research process,” Patton explained. “I help identify what’s needed in an area of research, prepare requests for proposals, oversee the review of applications, and follow investigators along their research process, making sure that they have the resources they need.”

Upon completion of a study, Patton helps develop a short report that explains the study findings and limitations, plus what it means for its intended audience.

Informing Policy

Patton explained that CAFEH’s meetings to communicate study results to the community were often attended by policymakers.

“State and local representatives and others who regularly showed up to our public meetings or read our reports are now working on a new state regulation to install air filters in buildings near highways and increase the amount of air quality monitoring,” she said.

A study by Patton and team on how air pollution decreased at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when road traffic was minimal, also informed new policies by the City of Somerville, Massachusetts. The new policies aim to create programs that reduce traffic congestion and on-street parking shortages, to ultimately improve air quality and pedestrian safety.

Through her work at the Health Effects Institute, Patton leads science that directly answers questions from policymakers. For example, she oversees studies to understand non-exhaust emissions, which come from vehicle brake pads, tires, and roads themselves wearing down over time.

“Currently, regulations that limit non-exhaust emissions are just beginning to be proposed, mainly because we have limited information about the extent of these emissions,” Patton said. “I hope that, with our research, we can contribute to new policy discussions.”

Lessons Learned from Mentors and Collaborators

Patton is grateful for the mentors who guided her along the way. In particular, she fondly remembers her first mentor, the graduate student she worked with while pursuing her undergraduate degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“She was studying how drinking water contaminated with arsenic was making people sick and I helped her with laboratory work,” Patton reminisced. “Seeing what she was doing inspired me to go to graduate school.”

Later, as a doctoral student, Patton enjoyed working with undergraduates who, like her, were passionate about future careers in science.

“Each of the undergraduates who worked with us had different interests and skillsets,” she said. “Some helped with modeling and others helped in our mobile lab. Helping them to further develop and use their skillsets was not just rewarding, but also fun.”

Another source of wisdom throughout Patton’s career has been the multiple community members who collaborated with her through the years.

“The different community groups we worked with [for CAFEH] had different purposes and expertise in diverse subjects that, taken together, improved the quality of our work,” Patton shared.

“Through conversations with partners I also learned the importance of communicating research to people in a way they can understand, as opposed to just publishing in scientific journals,” Patton explained. “We want to make sure we’re giving back to the residents who helped us, by sharing findings in a way they can use to take actions to protect their health.”

Linda McCauley, Ph.D., R.N. – Integrating Nursing and Environmental Research to Promote Community Health

April 17, 2023

When Linda McCauley, Ph.D., R.N., graduated from high school, most women followed one of two career paths, she said: nursing or education. Given her interest in women’s and children’s health, the choice was clear. McCauley, like her mother, became a nurse.

Though she loved providing patient care, McCauley was hungry to learn more about the factors that influence health. After completing a Master of Nursing at the Emory University Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing — where she now serves as dean — McCauley earned a Ph.D. in environmental health and epidemiology from the University of Cincinnati.

During her doctoral work, McCauley published one of the first studies showing that nurses who prepared and administered chemotherapy drugs were more likely to experience adverse health effects. Ever since, she has made it her mission to understand and reduce occupational and environmental chemical exposures.

When NIEHS requested applications for community-based intervention research in 1996 — the first federal funding opportunity for research projects partnered with communities — McCauley jumped at the opportunity.

“That’s what nurses do: work with communities,” McCauley said. “It was never the chemical that defined me, but the population that influenced my work.”

Understanding Agricultural Exposures

While working as a scientist in occupational and environmental toxicology at Oregon Health & Science University, McCauley won NIEHS funding to study pesticide exposure among Latino agricultural families in Oregon. Spanning 1996 to 2004, the community-based project relied on regular feedback from farmworker community representatives. According to McCauley, communities see nurses as trusted care providers, which helped her forge partnerships.

Among her findings, she learned that worker protective equipment was essentially nonexistent.

“Few workers reported wearing any type of protective clothing or equipment, and the large majority wore their work clothes into their homes,” she said. “At the time, there were no guidelines about take-home contamination, when farmworkers inadvertently take pesticides home on their clothing and skin, which is a potential source of exposure to their families.”

In 2004, McCauley transitioned to the University of Pennsylvania, where she spent five years as a professor of community health and the Associate Dean of Nursing Research. There, she evaluated the health effects of pesticide exposure, focusing specifically on neurological outcomes in both the workers and their children.

When findings showed associations between pesticide exposure and deficits in neurobehavioral performance, such as cognitive and motor function, McCauley knew she had to dive deeper into environmental exposures, particularly among vulnerable children.

She began her tenure as Dean of Nursing at Emory University in 2009. In collaboration with the Farmworker Association of Florida — a partnership that continues today — McCauley initiated a study on the health effects of multiple agricultural exposures in pregnant farmworkers and their children.

“Agricultural work presents a variety of hazards to pregnant workers, including an increased risk of heat stress, pesticide exposure, and musculoskeletal injuries,” she said. “By promoting farmworkers’ health, we can also improve the health of their children — not just during childhood, but throughout their lives.”

Advancing Children’s Health

In 2015, McCauley established the Children’s Environmental Health Center at Emory University, an initiative funded by NIEHS and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The center studied how environmental exposures during pregnancy and infancy, along with the microbiome and the immune system, influence brain development.

She now leads Emory’s CHARTER Center, which fosters partnerships between researchers and communities to decrease environmental exposures and translate scientific findings into action.

“CHARTER has allowed me to use my background in community outreach and education to study the actual science behind research translation and communication,” McCauley said.

Tailoring Community Messages

In partnership with the University of Georgia, CHARTER is developing a virtual reality platform to communicate environmental health risks to community members and encourage pro-environmental action.

“During trial runs with community members, they absolutely loved virtual reality and were so engaged with the platform,” McCauley said. “It’s a prime example of how we are always learning new perspectives and new ways to communicate.”

McCauley learned early on the importance of tailoring messages to community preferences. As part of a 2002 study, she developed an educational video explaining pesticide risks to farmworkers.

“Focus group sessions with Oregon farmworkers revealed that community members wanted care providers to deliver information about potential exposures,” McCauley said. “Farmworkers in Florida, however, preferred messages from other farmworkers. All communities are different.”

McCauley and team edited the video to match preferences of each community, including preparing educational messages in Indigenous languages when needed. According to McCauley, listening to community needs and preferences resulted in increased overall pesticide knowledge and protective behaviors.

After decades of collaborative research with communities, McCauley has learned that achieving goals depends on the level of commitment of both the research team and the community.

“Every community has its own history, power struggles, and trust relationships,” she said. “There is no fast way to form relationships. You have to be immersed in the community to understand cultural nuances and develop appropriate messages to really improve public health.”

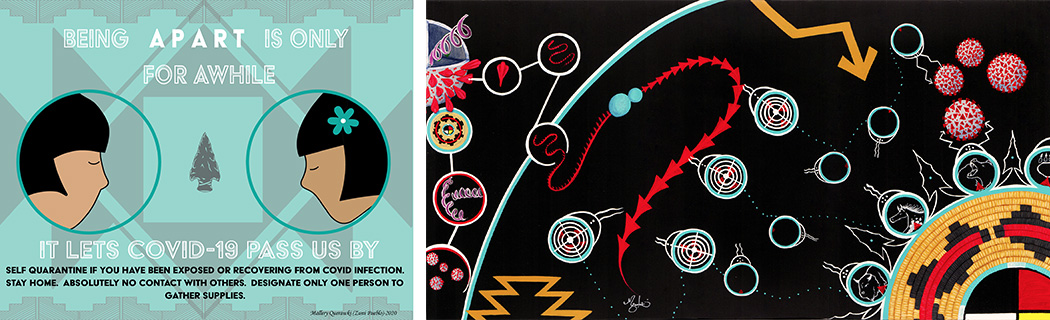

Mallery Quetawki – Using Art to Improve Environmental Health Literacy Among Indigenous Tribes

March 29, 2023

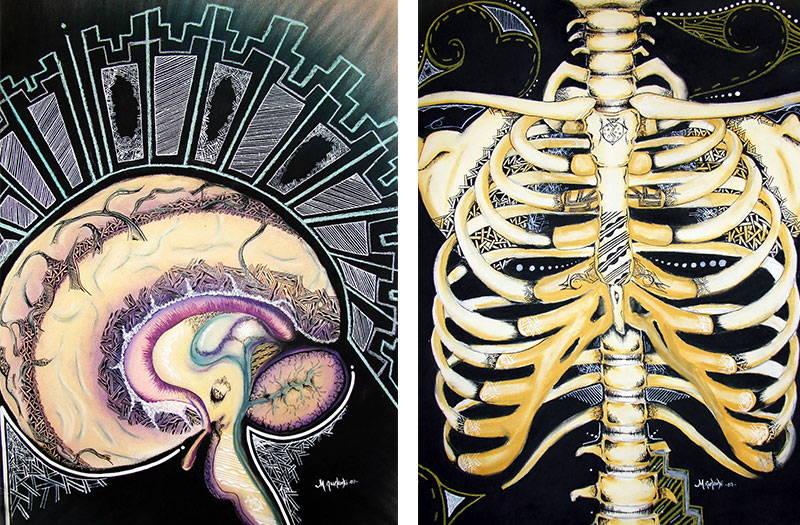

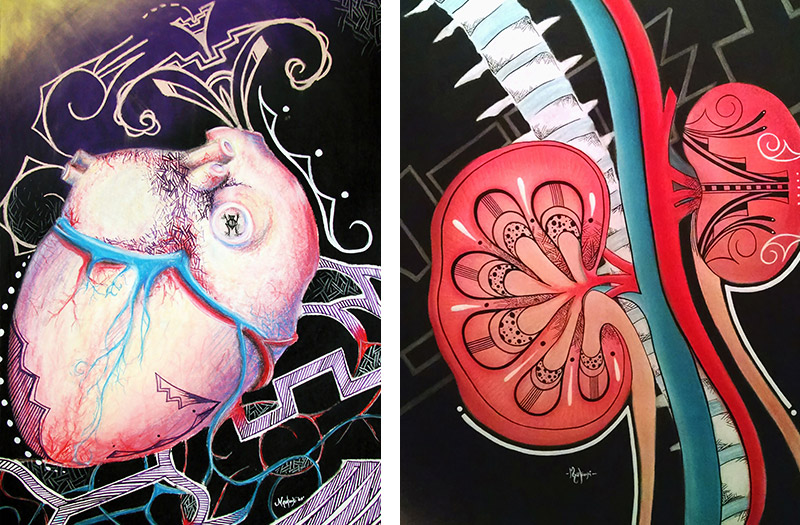

Artist Mallery Quetawki’s journey into science communication began with a series of chalk pastel drawings featuring the heart, brain, and other parts of human anatomy. She created the pieces in 2007 after spending several summers as a healthcare intern at the Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute in California. As a member of the Pueblo of Zuni Tribe in New Mexico, Quetawki wanted to convey how science had become integral to her identity.

Several years later, the Zuni Indian Health Services Hospital displayed her drawings, and a surprising thing happened. Incoming patients began examining the pieces, then discussing them with their healthcare providers. Some patients even asked how their own organs could stay looking as healthy as the ones in the drawings.

“The art created a wave of people asking about their personal health,” said Quetawki, who worked at the University of New Mexico Hospital in Albuquerque at the time. “I realized, ‘Holy smokes, this is an educational tool!’”

Quetawki is now the artist-in-residence at the University of New Mexico (UNM) College of Pharmacy’s Community Environmental Health Program (CEHP), where she blends science and art to improve environmental health literacy among New Mexico’s Indigenous communities. Among various UNM departments and programs, she works with the NIEHS-funded Metals Exposure and Toxicity Assessment on Tribal Lands in the Southwest (METALS) Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center.

Bridging Art and Science

Quetawki's twin interests in art and public health stem from her Pueblo of Zuni roots. Following the rich Zuni tradition of art- and handicraft-making, Quetawki has painted all her life and remembers her parents creating art as well.

As a Tribal member, Quetawki is also aware of health disparities among her people, such as higher rates of type 2 diabetes and end-stage renal disease, compared to the general U.S. population. However, she has noticed that Tribal members tend to seek medical treatment only in dire situations. As a result, many fear hospital visits, associating them with tragedy, according to Quetawki.

Those experiences inspired her to pursue a bachelor’s degree in biology, with a minor in studio art, at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. After graduating, she became a patient care technician in the UNM hospital system, while continuing to make art on the side.

Art as a Health Literacy Tool

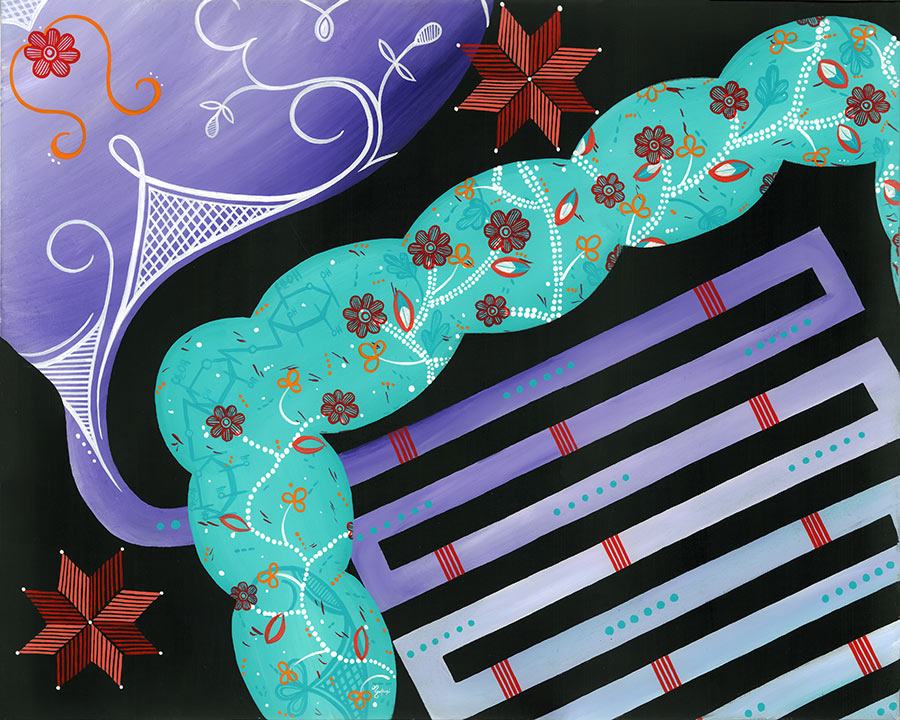

In 2017, UNM SRP Center director Johnnye Lewis, Ph.D., approached Quetawki about creating art to help communicate SRP research to Indigenous partners who lived near abandoned uranium mines. They wanted to illustrate how uranium and other metals in mining waste damage DNA in immune cells.

“At a meeting held in the Navajo Nation, Navajo, Crow, and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe community leaders explained they were visual learners, so translation through art would really help them understand health information,” Lewis recalled. “I had just been shown Mallery’s art while presenting some of our research to Zuni clinicians. The synchrony of those events was hard to ignore!”

With input from the SRP team, Quetawki created a series of paintings showing how metals affect immune cell DNA. She used traditional symbols like baskets, totem animals, and bead work to convey DNA damage and repair. The designs emulate blankets from multiple Northern Plains Tribes to signify how all are connected.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought another opportunity to communicate science through art. Quetawki noticed that Puebloans were frustrated with federal health agencies’ quarantine instructions, because the messages did not reflect Indigenous cultural needs.

“On the Zuni Pueblo, being told not to gather was a big cultural taboo,” Quetawki explained. “We do everything as a village. Tribal communities were mourning not only losing people, but also loss of ceremony and togetherness.”

To encourage acceptance of federal recommendations, Quetawki and her colleagues created culturally sensitive public service announcements, posters, and videos. She also illustrated how mRNA vaccines work, in an effort to combat vaccine hesitancy and misinformation.

Raising Cancer Awareness

Recently, Quetawki has been collaborating with the UNM Comprehensive Cancer Center to improve their outreach to the 19 Pueblo Tribes. Although the Tribes are separate, sovereign, and have distinct cultures, Quetawki is drawing on common cultural elements to create messaging around sensitive topics.

Pueblo cultures emphasize a connection between body and spirit and keeping the body whole. For Tribal members, removing tissue samples, and especially storing them for research after death, invokes spiritual harm.

Quetawki is collaborating with UNM communication faculty and students to create brochures and pamphlets, mixing art with simplified language explaining cancer research and treatments.

“Not everything in science and health can be translated into these Indigenous languages,” Quetawki explained. “That’s where art comes in: It creates a common language that bridges those gaps.”

Opportunities and Accolades

Although artists-in-residence are gradually becoming more common in environmental health, few artists work at the nexus of art, health science, and engagement with Indigenous peoples, according to Quetawki.

“What I do and how I do it are pretty unique,” Quetawki noted. “There is very little literature on communicating health science to Indigenous peoples through art — there’s nothing to cite — so my team and I are producing the literature now.”

For example, she is working on a paper for a scientific journal about communicating cancer research and treatment information to Native American communities. Quetawki has also received a pilot grant from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to expand her art and science communication activities, including recruiting and training more artists and other storytellers to share health information with other Indigenous Tribes.

“We are planning summer internships that pair artists with scientists as a way to broaden the success of our Community Environmental Health Program centers,” Lewis said.

Additionally, Quetawki’s work is attracting attention from internationally renowned institutions. On July 13, her mural of uranium extraction and remediation will be projected onto the façade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. This work appeared in the 2021-22 show, “Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology,” at the Institute of American Indian Arts Museum of Contemporary Native Arts (IAIA MoCNA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and is part of a traveling exhibit until 2024.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has also commissioned a painting depicting the gut microbiome, the collection of microorganisms living in the digestive tract.

For her part, Quetawki is excited about future opportunities to educate Indigenous peoples about environmental health.

“I want to continue helping others by using my cultural knowledge.”

Kevin Lane, Ph.D. – Applying Spatial Analysis to Air Pollution Research

February 28, 2023

Though two decades have passed, environmental health scientist Kevin Lane, Ph.D., still vividly remembers his first research assignment: tracking air pollution exposures among workers in the trucking industry for a large occupational health study. During college, Lane assisted with data collection, traveling to shipping docks and observing what were at times abysmal work environments.

To stay warm on below-freezing nights, for example, some forklift drivers would wrap cardboard and cellophane around their vehicles’ propane tanks, in attempt to redirect lost heat into their cabs.

“They were drawing in exhaust and basically asphyxiating,” Lane recalled. “Seeing conditions like that really hit home.”

Through his work on the study — the largest, most comprehensive exposure assessment of trucking industry workers at the time — Lane saw the power of research to improve lives.

“It struck me that research could change national policy, as well as inform simple strategies to improve a person’s life, like giving dock workers more breaks when it’s cold,” he said.

Driven by that early fieldwork experience, Lane pursued a master’s degree in urban and environmental planning at Tufts University, followed by a doctoral degree in environmental health at Boston University (BU), and postdoctoral work as a Yale Climate and Energy Institute fellow.

Now an assistant professor at BU, Lane continues to study the effects of air pollution and the built environment on human health in the U.S., as well as abroad. Often his research entails using geographic information systems (GIS) and computer modeling to visualize relationships between populations and exposure data.

“I found a passion for geospatial analysis during my doctoral studies,” Lane said. “I now push my students to find new applications in GIS, computer science and programming, and planetary sciences that we can use to improve health.”

Sticking With It

Among his various activities, Lane contributes to the Community Assessment of Freeway Exposure and Health Study, or CAFEH, a project he first worked on as an NIEHS doctoral trainee.

Funded by NIEHS and led by Doug Brugge, Ph.D., of the University of Connecticut, CAFEH launched as a community-based participatory research study. The original goal was to understand associations between highway pollution — specifically ultrafine particles — and cardiovascular health in Boston-area communities.

Ultrafine particles are a byproduct of combustion and tend to concentrate in highly trafficked areas. Compared to larger particulate matter, ultrafine particles usually do not disperse from their source and therefore disproportionally affect people living near highways.

Growing evidence suggests that exposure to this microscopic matter may contribute to respiratory, neurological, and cardiovascular problems. For example, in 2016, Lane and colleagues published preliminary findings showing that exposure to ultrafine particles was linked to a biological marker for increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Subsequent CAFEH studies have also hinted at associations between ultrafine particle exposures and blood pressure changes, hypertension, and heart diseases.

More recently, Lane and teammates offered new considerations for metrics used in ultrafine particle exposure studies. Reporting in 2021, the team suggested that annual exposure to ultrafine particles might not reflect the cumulative effect of short, high-intensity exposures.

“Exposure is highly dependent on times of day and the environment you are in at any given time,” Lane explained. “For example, some people who live next to a congested corridor may be working elsewhere during peak traffic times.”

Lane is gratified to see CAFEH research informing local change. For example, CAFEH findings informed an updated master plan for Boston Chinatown. In addition, input from CAFEH researchers and community partners encouraged developers of several buildings near highways to incorporate high-grade air filtration measures.

“In my eyes, CAFEH is as close to perfect as you can get for a community-based participatory research study,” he said. “It was not about researchers descending upon communities with an idea. It was about working with them to formulate an idea from the start and integrating them throughout.”

New Research Takes Off

Over the past few years, Lane has widened his focus from road traffic to air travel, with the aim of informing requirements set by the Federal Flight Administration (FAA) for aircraft compliance with federal air quality standards. At the start of the pandemic, he seized the opportunity to study what happens to air pollution when plane traffic essentially stops.

“We don’t have a great understanding of how many ultrafine particles are coming from planes in flight, planes on the ground, and the traffic that comes from the airport,” he explained. “This was a once-in-lifetime event where we literally saw a drop-off to almost zero in aviation activity occurring at some points on certain days.”

With FFA funding, Lane, BU doctoral student Sean Mueller, and colleagues measured changes in ultrafine particle concentrations at sites near Boston’s Logan Airport during early and later stages of the pandemic and compared them to pre-pandemic levels.

Reporting in 2022, they showed that ultrafine particle numbers precipitously declined in the first few months of the crisis. As road traffic resumed, monthly ultrafine particle levels returned to pre-pandemic averages. However, at specific sites located downwind from the airport, particle counts remained lower than average until aviation picked up again, suggesting that planes uniquely contribute to ultrafine particle pollution in certain geographic locations, according to the authors.

Lane’s team is now crunching reams of data to see how different aspects of air travel, such as arrivals and departures, contribute to ultrafine particle pollution.

“Our ultimate goal is to create an ultrafine particle model of the area, so we can run health studies to understand the impact of exposure to aviation-related ultrafine particles in the greater Boston community,” he explained.

The runway ahead reminds Lane of the route he took to get here, and the people who encouraged him along the way.

“I think where I am today is a product of the mentors, like Doug Brugge and Madeleine Scammell, of Boston University, who believed in me,” he said. “I want to give research assistants and doctoral students the same opportunities that were given me. We need to cultivate them — they are our future innovators.”

Joseph Hamm, Ph.D. – Fostering Trust-Building to Promote Environmental Health

January 25, 2023

As a social scientist, Joseph Hamm, Ph.D., has worked with a variety of government organizations, including police departments, courts, natural resource agencies, public health departments, and other state and federal entities.

Currently a lead on the Community Engagement Core (CEC) within the Michigan State University Superfund Research Program (SRP), he strives to define and measure trust between the public and the government.

“Working across fields gives me opportunity to combine theoretical understandings of trust from organizational psychology and my practical experience with environmental managers to develop a more nuanced understanding of the best opportunities for building trust,” Hamm said. “Being a part of the CEC has given me the ideal case for taking ideas from one context into another.”

His overarching goal is to contribute to a deeper, fuller understanding of trust, one that crosses disciplines and helps different groups to work collaboratively toward better outcomes for community health and safety.

Bridging Fields

Hamm became interested in the concept of trust through his studies of jury decision-making. In a project focused on reducing failure-to-appear rates, he explored how perceptions of government play into whether people arrive for duty. He was inspired by concepts in the organizational psychology field, where trust scholars have long been interested in the nature and dynamics of trust.

While working with criminal justice agencies, Hamm became a trainee in the National Science Foundation Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship Program, which fosters interdisciplinary learning experiences. He soon began working with environmental managers and noticed a heavy emphasis on defining problems collaboratively between policymakers and the public.

As his research evolved, he crossed into environmental health. In his work with the CEC, Hamm and an interdisciplinary group of researchers began looking at government organizations’ community engagement in Midland, Michigan. The city is home to a chemical manufacturing plant that for decades contaminated the local watershed with dioxins, a family of industrial byproducts that can cause a wide range of negative health effects.

“The communities I work with are often in the difficult position of having an important local economic driver also contributing to environmental pollution and potential health problems,” Hamm noted. “I’m interested in understanding these complex trust dynamics between the community, regulatory agencies, and industry, to help all these groups work together in protecting community health.”

Pinpointing Community Concerns

Hamm presented on trust and why it is important at the Engaging Communities in the State Courts Initiative kick-off meeting, during his graduate education at University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The initiative was designed to help state courts understand what problems the public saw and how they could best be addressed. (Photo courtesy of Joseph Hamm)

Hamm’s role in the Midland project was to examine the trust relationships between government agencies, companies releasing chemicals, and residents.

He discovered that many community members had reported that ongoing cleanup efforts were proceeding well, and that the situation was largely under control. Their shock at the pollution — and by their city’s designation as an “area of concern” by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) — had apparently dissipated.

“There was a lot of concern initially,” Hamm said. “Thirty years later, what had been an incredibly contentious issue has, more or less, stabilized. The chemical company is working directly with EPA on remediation, and there is not a lot of skepticism in the community about whether they’re doing a good job.”

Also, because the company has been a long-time employer and supports Midland philanthropically, community members tend to have a high level of trust in the business, Hamm explained. The conversations he heard in Midland centered less on health than on property values, and somewhat on concern for possibly losing the chemical plant as an employer.

In addition, Hamm learned that decades of outreach and education by government agencies had enhanced public health behaviors. Many Midland residents were taking recommended precautions, like adapting their fish consumption habits. To maintain that momentum and prevent redundant efforts, Hamm and his team reconsidered their approach to community engagement. They shifted to supporting the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) in their existing engagement efforts, contributing new ideas about how to continue building and maintaining trust.

“We developed a strategy for helping MDHHS better engage the community. It’s a strategy that efficiently builds trust because it has MDHHS listening to the communities, teasing out the vulnerabilities they feel, and demonstrating MDHHS is working to protect those vulnerabilities,” Hamm explained.

Meanwhile, the nearby cities of St. Clair Shores, Saginaw, and Otsego — where the CEC team is now focusing its efforts — are at a different juncture. Dioxins released into the environment from a paper manufacturing facility are a problem, and residents appear more ambivalent about how the state is managing the contamination, according to Hamm.

He hopes to improve the relationship between residents and government organizations like MDHHS. If communities feel they can trust governance, he explained, they may be more likely to adopt government health and safety recommendations to protect themselves. Or, they will at least be better equipped to make informed decisions.

“Our role is to create a feedback loop between the community and the state that is focused on finding the particular vulnerabilities the community is feeling and to help MDHHS work that knowledge into the engagement they are already doing,” he said.

Coming Full Circle

As a next step, Hamm seeks to produce a new model for how to earn and protect trust in community engagement work that is usable across disciplines. He will take the lessons learned from the CEC’s work and develop a project focused on a criminal justice agency that has struggled to build trust in its community.

“I want to work with a police department and use the same methods of listening to the community’s concerns, then working those concerns back into the department’s outreach,” Hamm said. “Our trust-building approaches can benefit community health in places facing many kinds of compounded challenges.”