Introduction

Arsenic is a naturally occurring, semimetallic element widely distributed in the Earth’s crust. Arsenic levels in the environment can vary by locality, and it is found in water, air, and soil.

There are two general forms of arsenic:

- Organic arsenic compounds contain carbon. There is no relation between organic arsenic and “organic” food, which refers to food produced using no synthetic fertilizers or pesticides.

- Inorganic arsenic compounds do not contain carbon. Research indicates that inorganic arsenic is more toxic and its associated health effects are more severe.

All arsenic is toxic to humans and can affect people of any age or health status.

Because of its significance in global public health problems, studies of arsenic, arsenic metabolism, and the health effects associated with arsenic exposure are conducted by NIEHS, particularly through its Superfund Research Program (SRP). Many scientists, pediatricians, and public health professionals are concerned about the health effects of low-level exposures to arsenic in people. These health effects may be barely noticeable at first, but if exposure continues, severe long-term effects may result.

What Are Sources of Arsenic?

The most common source of arsenic in people is contaminated drinking water. Because arsenic occurs naturally, waters that come in contact with particular rocks and soils may contain it. Arsenic levels tend to be higher in groundwater sources, such as wells, than surface sources, such as lakes or reservoirs.

Contamination from mining and fracking, coal-fired power plants, arsenic-treated lumber, and arsenic-containing pesticides also contributes to increased levels of arsenic in certain locations.

Arsenic may be found in foods, including rice and some fish, due to its presence in soil or water. As a naturally occurring element, it is not possible to remove arsenic entirely from the environment or food supply.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) monitors and regulates levels of arsenic in certain foods. FDA prioritizes monitoring inorganic arsenic levels in specific foods that are more likely to be eaten by young children, such as infant rice cereal and apple juice.

Arsenic may be a component of air pollution. People could also touch dust containing arsenic, but this is not a major way to be exposed.

The U.S. Geological Survey studies sources of arsenic to help local health officials better manage water resources.

How Much Arsenic Can Be in Drinking Water?

The maximum level of inorganic arsenic permitted in U.S. drinking water is 10 parts per billion (ppb). This standard was set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Some states, such as New Jersey, have more stringent drinking water standards for arsenic than 10 ppb. There are no arsenic water standards for private wells.

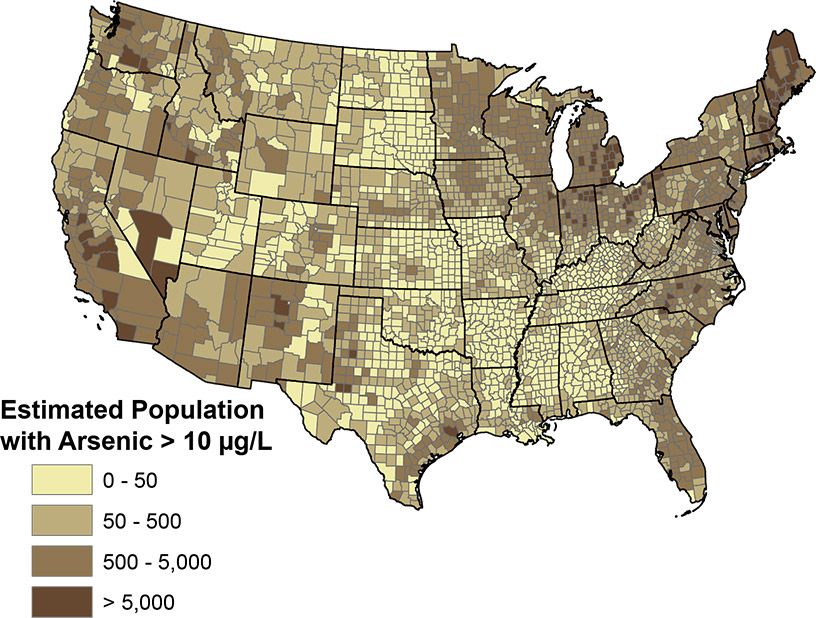

Because arsenic is tasteless, colorless, and odorless, testing is needed for detection. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has analyzed water samples from more than 5,000 wells across the United States and determined that at least 7 percent of the wells had arsenic levels above the current EPA standard of 10 ppb. They estimate that about 2.1 million people in the U.S. may be getting their drinking water from private domestic wells considered to have high concentrations of arsenic. Arsenic levels in the U.S. tend to be higher in rural communities in the Southwest, Midwest, and Northeast.

How Can I Find Out Whether There Is Arsenic in My Drinking Water?

Because you cannot taste or smell arsenic, the water must be tested. If your home is not on a public water system, you can have your water tested for arsenic. Your state certification officer should be able to provide a list of laboratories in your area that will perform tests on drinking water for a fee.

How Do I Remove Arsenic From My Drinking Water?

You cannot remove arsenic by boiling water. Additionally, chlorine bleach disinfection will not remove arsenic. Water softeners are not a way to remove arsenic from drinking water.

Certain filtration systems can remove arsenic from water. Consider water treatment methods such as reverse osmosis, ultra-filtration, or ion exchange. Contact your local health department for recommended procedures.

How does arsenic affect people?

Arsenic affects a broad range of organs and systems including:

- Cardiovascular system

- Endocrine system

- Immune system

- Liver, kidney, bladder organs

- Nervous system

- Prostate glands

- Respiratory system

- Skin

Fact Sheets

Arsenic and Your Health

What is NIEHS Doing?

Because of its significance as a global public health problem, studies of arsenic, arsenic metabolism, and the health effects associated with arsenic exposure are a priority for the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), the National Toxicology Program (NTP), and several other organizations involved in research, regulation, and health care.

NIEHS, particularly the Superfund Research Program through its grantees, and NTP conduct arsenic research, which includes the following:

Fundamental Arsenic Research

Researchers have learned that both short-term and long-term exposure to arsenic can cause health problems, but they are just beginning to understand how arsenic works in the body — what is referred to as its modes of action.

For example, researchers are finding that arsenic, even at low levels, can interfere with the body’s endocrine system. The endocrine system is what keeps our bodies in balance and guides growth and development. In several cell culture and animal models, arsenic has been found to act as an endocrine disruptor, which may underlie many of its health effects. Other mechanisms are also likely contributors to arsenic’s health effects.

Once inside the human body, arsenic can be metabolized into at least five different chemical forms, each with very different toxicities. Understanding arsenic metabolism is essential to understanding both the impacts of arsenic exposure on human health and the individual variation in susceptibility to arsenic-caused diseases. Researchers believe that genetic variation could be a determinant of individual variation in arsenic metabolism and related toxicities. They also have found that microbes in the human digestive system – known as the gut microbiome – may complement a person’s ability to metabolize arsenic, particularly in the first few weeks of life.

Arsenic and Cancer

Both forms of arsenic are known human carcinogen associated with skin, lung, bladder, kidney, and liver cancers. A study from the NTP laboratory that replicates how humans are exposed to arsenic through their whole lifetime found that mice exposed to low concentrations of arsenic in drinking water developed lung cancer. The concentrations in the drinking water given to the mice were similar to what humans who use water from contaminated wells might consume.

Early-life Exposures to Arsenic and Development

Arsenic exposure can predispose children to health problems later in life. Researchers supported by the SRP center at the University of California, Berkeley, found increased incidence of lung and bladder cancers in adults exposed to arsenic early in life, even up to 40 years after high exposures ceased. These findings provide rare human evidence that an early-life environmental exposure can be associated with a high risk of cancer as an adult.

Work from researchers at NIEHS has identified other effects of arsenic exposure in animal models. Pregnant mice that drank water containing inorganic arsenic, at concentrations relevant to human consumption and at levels that trigger tumor growth, resulted in obesity in the male offspring. Males experienced negative reproductive effects, such as decreased fertility.

Arsenic and Preterm Birth

Preterm birth, which occurs before 37 weeks of pregnancy, is a risk factor for newborn mortality and adverse health effects in childhood and later in life. Using umbilical cord blood from pregnant women in Bangladesh, NIEHS-funded researchers identified elevated levels of several metals, including arsenic, as key drivers of preterm birth risk. The team also constructed metrics or risk scores to measure the effects of chemical mixtures and found that women with the highest scores were nearly four times more likely to experience preterm birth than women with the lowest scores.

Arsenic and Diabetes

Several studies, including a review of the literature by NTP, have suggested an association between low-to-moderate levels of arsenic and metabolic diseases, such as diabetes. For example, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill SRP Center have shown that arsenic exposure can disrupt insulin-secreting cells of the pancreas.

NIEHS-funded researchers examined the association of arsenic in federally regulated community water systems and unregulated private wells with type 2 diabetes incidence. Data from two prospective studies were used, which included American Indian communities and other racially and ethnically diverse urban U.S. communities. The 2024 study reports that low to moderate water arsenic levels (<10 µg/L) were associated with increased incidence of type 2 diabetes.

Health Disparities

Exposure can be from naturally occurring arsenic that is not removed from drinking water or industrial processes that release arsenic into the environment. Health disparities related to arsenic are influenced by differing protective actions taken by individuals and communities, such as testing and treating water and soil.

Researchers at the Columbia University SRP Center found that people belonging to racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S. are exposed to significantly higher arsenic concentrations in their drinking water compared with non-Hispanic White residents.

Tribal lands are affected by more than 15,000 hazardous waste sites and 7,000 abandoned mines that can release toxic metals such as arsenic and uranium. In collaboration with tribal communities from North Dakota and South Dakota, researchers at the Columbia University SRP Center found that Native Americans from the Northern Plains have experienced urinary arsenic levels 2.5 to 5 times higher than other U.S. populations, likely contributing to a higher burden of cardiovascular disease.

The University of New Mexico Metal Exposure and Toxicity Assessment on Tribal Lands of the Southwest (METALS) SRP Center has worked in partnership with Indigenous partners to show that weathering of the metal mixtures in the millions of tons of mining waste has produced potentially harmful nanoparticles. The researcher’s health studies have shown that exposure to these metal mixtures increases the prevalence of multiple chronic diseases.

Incarcerated people in the Southwestern U.S. are more likely to have higher levels of arsenic in their water, and may also lack access to alternative drinking sources, such as bottled water. A NIEHS-funded study found that the average arsenic concentrations in correctional facility water systems were twice as high as other systems in the region and four times higher than water systems across the U.S.

Individuals with low socioeconomic status (SES) may be more vulnerable to the harmful effects of arsenic exposure. A study from the University of California, Berkley SRP Center showed that arsenic-exposed residents of Chile with lower SES were more likely to develop diabetes than those with higher SES.

Translational Research on Arsenic

At least 30 million people in Bangladesh are exposed to arsenic in their drinking water. Researchers have found that arsenic education, coupled with water testing programs, can increase knowledge in the population, and result in reduced arsenic exposures, when safe drinking water sources are made available.

A scientific review of two randomized clinical trials found that folic acid supplements may reduce blood arsenic levels and make it easier to get rid of arsenic through the urine in individuals chronically exposed to arsenic-contaminated drinking water. One of those trials showed that just 400 micrograms a day of folic acid, the U.S. Recommended Dietary Allowance, reduced total blood arsenic levels in a Bangladesh study population by 14%.

SRP-funded research centers have worked closely with affected communities to address their concerns and provide them with important information regarding potential exposure to arsenic and its health implications. For example, the SRP center at Dartmouth College evaluated private well testing behavior, including barriers. They worked to encourage private well testing and empower well water users with the tools they need to keep their drinking water safe, including a website, community toolkit, and online application.

A bill to sharply lower the drinking water limit for arsenic in New Hampshire was signed into law in 2019. The new rule, informed by Dartmouth research and outreach efforts, sets the state drinking water standards at 5 ppb, which is half of the federal limit. According to the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services, the new limit will better protect human health by reducing the number of arsenic-related illnesses and deaths.

Further Reading

Stories from the Environmental Factor (NIEHS Newsletter)

- Path to Food Safety Requires Multidisciplinary Approach, Experts Say (January 2023)

- Tribal Environmental Health Strengthened by NIEHS-Funded Scientist and Her Team (September 2022)

- Webinar Recognizes Early-career Scientists' Research on Lead, Arsenic (March 2022)

- Educational Tool Highlights COVID-19 and Arsenic Research (March 2022)

- E-cigarettes Expose Users to Toxic Metals Such As Arsenic, Lead (February 2022)

- Arsenic, Uranium Mix May Increase Diabetes Risk in American Indians (November 2021)

Additional Resources

- Arsenic and Drinking Water — U.S. Geological Survey

- Arsenic as a Cancer-Causing Substance — National Cancer Institute

- Arsenic Fact Sheet — World Health Organization

- Arsenic in Food and Dietary Supplements — Food and Drug Administration

- Arsenic Literature Collection — Environmental Health Perspectives, a peer-reviewed journal supported by NIEHS

- Drinking Water Arsenic Rule — Environmental Protection Agency

Related Health Topics

This content is available to use on your website.

Please visit NIEHS Syndication to get started.