While Jennifer Richmond-Bryant, Ph.D., was studying for a degree in civil and environmental engineering at Cornell University, she heard that workers in nearby municipal offices were experiencing “sick building syndrome.” This condition occurs when acute health problems coincide with time spent in a building. In such cases, exposure to environmental contaminants may be the cause.

“That got me more interested in pursuing an environmental health angle, because it highlighted that environmental issues are really health issues,” Richmond-Bryant recalled. “I ended up doing my master’s in industrial hygiene. For my Ph.D., I studied the fluid mechanics of environmental transport, which is how fluids influence the movement of particles and pollutants.”

After completing her Ph.D., Richmond-Bryant worked as a contractor for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), researching how people encounter environmental contaminants. She previously studied the transport and dispersion of traffic-related pollution in New York City. After leaving the EPA, she became a professor at City University of New York and examined New York neighborhoods with high asthma diagnoses to deduce if pollution was correlated with asthma cases.

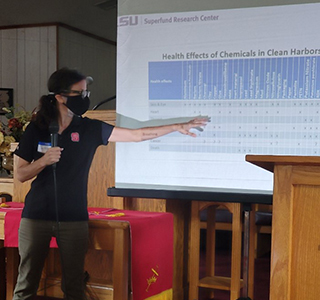

Richmond-Bryant is now an associate professor of geospatial analytics at North Carolina State University. She is also an investigator with the NIEHS-funded Louisiana State University (LSU) Superfund Research Program (SRP), where she studies the effects of air quality on health, and a co-investigator for the center’s Community Engagement Core.

Burning Questions in Colfax

Richmond-Bryant’s research sprang from community concerns in Colfax, Louisiana, where a thermal waste treatment plant releases combustion byproducts into the air. The contaminants include environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs) – highly reactive particles that remain stable for long periods and that have been implicated in heart and lung problems.

In 2010, the waste plant ramped up operations. Shortly thereafter, residents began reporting adverse health effects, such as cardiovascular issues, stomach cancers, and thyroid disease. A coalition of Colfax residents reached out to LSU, asking for researchers to investigate.

Richmond-Bryant and her team are now studying air pollutant levels in the area that may be contributing to the residents’ health problems. In March 2023, they completed a year-long data collection effort, and are in the initial stages of analyzing their findings.

“We’re still working through the results, but we did find levels of EPFRs that were higher than the norm, even for an urban area. This was alongside other contaminants like dioxins and metals, all substances that have been linked to health effects in humans,” she said.

The team shared their results with the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) this past June, just after the thermal treatment plant applied for license renewal. After seeing the preliminary data, the Louisiana DEQ prohibited open burning at the site.

“Seeing our work actually help people is a great feeling,” said Richmond-Bryant. “That’s when you feel like you’ve been doing good work.”

At the community’s request, her team will continue monitoring air quality at the site. According to Richmond-Bryant, although open burning is now prohibited, Colfax residents still worry that closed burning at the site will have negative effects on the community.

“Continued monitoring will allow us to see how things are changing, if there are improvements, or if other contaminants are introduced,” she said.

Collecting Oral Histories

Engagement with Colfax community members is a critical part of this SRP project and has provided important data. For example, Richmond-Bryant’s team collected oral histories from the members of the Colfax community about their own health experiences to map the historical effects of the waste plant.

According to Richmond-Bryant, health statistics in small, rural towns like Colfax can be incomplete because fewer people seek medical assistance, which makes quantitative measures like hospital admissions less reliable. To supplement the limited data, her team spoke with residents, both in-person and by phone about their health.

“We wanted to learn about the residents’ experiences over time, how their health changed and how their community changed,” said Richmond-Bryant. “These oral histories bring out health issues that we wouldn’t have seen if we only looked at the numbers.”

These oral histories highlighted concerns of Colfax residents. According to Richmond-Bryant, the Colfax community has historically been excluded from decisions about the thermal treatment plant.

“Nobody asked the Colfax community when the plant was built. For a long time, community members didn’t have a voice in how the plant operated,” she said. “We wouldn’t have known about these issues if we didn’t do these oral histories and listen to residents.”

For Richmond-Bryant, listening and responding to people is essential to research.

“The most valuable work I’ve done is in response to what I learned from community members. If your work isn’t consistent with what the community is experiencing, then it doesn’t make sense to pursue,” she said. “It’s our responsibility to support the communities that let us in and allowed us to collect data. Their observations are paramount.”

Jennifer Richmond-Bryant