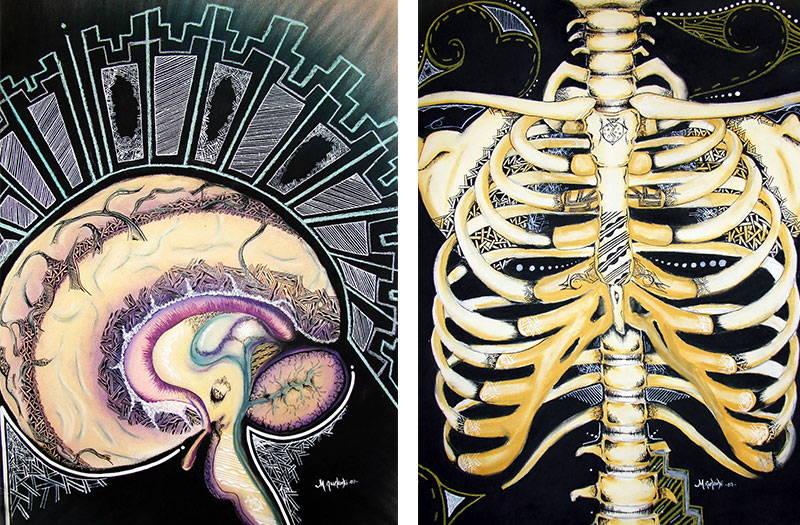

Artist Mallery Quetawki’s journey into science communication began with a series of chalk pastel drawings featuring the heart, brain, and other parts of human anatomy. She created the pieces in 2007 after spending several summers as a healthcare intern at the Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute in California. As a member of the Pueblo of Zuni Tribe in New Mexico, Quetawki wanted to convey how science had become integral to her identity.

Several years later, the Zuni Indian Health Services Hospital displayed her drawings, and a surprising thing happened. Incoming patients began examining the pieces, then discussing them with their healthcare providers. Some patients even asked how their own organs could stay looking as healthy as the ones in the drawings.

“The art created a wave of people asking about their personal health,” said Quetawki, who worked at the University of New Mexico Hospital in Albuquerque at the time. “I realized, ‘Holy smokes, this is an educational tool!’”

Quetawki is now the artist-in-residence at the University of New Mexico (UNM) College of Pharmacy’s Community Environmental Health Program (CEHP), where she blends science and art to improve environmental health literacy among New Mexico’s Indigenous communities. Among various UNM departments and programs, she works with the NIEHS-funded Metals Exposure and Toxicity Assessment on Tribal Lands in the Southwest (METALS) Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center.

Bridging Art and Science

Quetawki's twin interests in art and public health stem from her Pueblo of Zuni roots. Following the rich Zuni tradition of art- and handicraft-making, Quetawki has painted all her life and remembers her parents creating art as well.

As a Tribal member, Quetawki is also aware of health disparities among her people, such as higher rates of type 2 diabetes and end-stage renal disease, compared to the general U.S. population. However, she has noticed that Tribal members tend to seek medical treatment only in dire situations. As a result, many fear hospital visits, associating them with tragedy, according to Quetawki.

Those experiences inspired her to pursue a bachelor’s degree in biology, with a minor in studio art, at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. After graduating, she became a patient care technician in the UNM hospital system, while continuing to make art on the side.

Art as a Health Literacy Tool

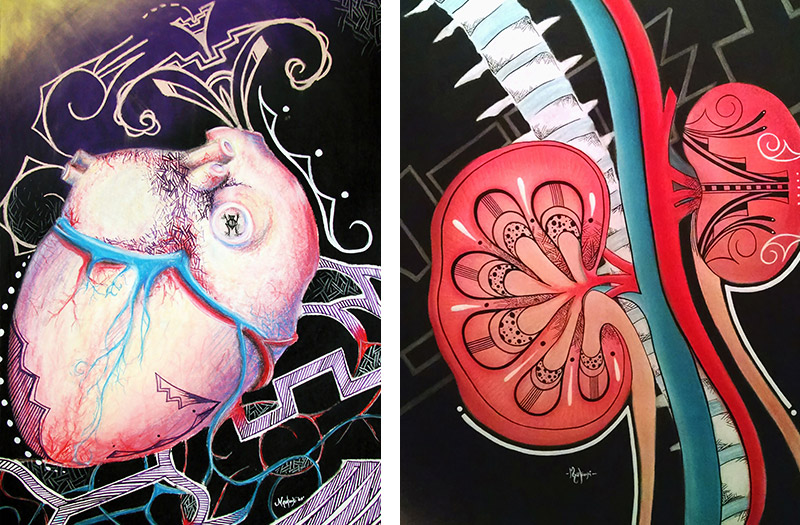

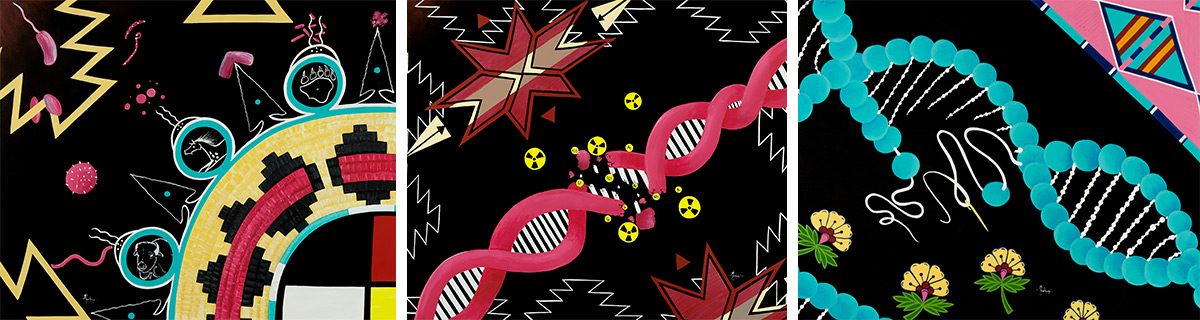

In 2017, UNM SRP Center director Johnnye Lewis, Ph.D., approached Quetawki about creating art to help communicate SRP research to Indigenous partners who lived near abandoned uranium mines. They wanted to illustrate how uranium and other metals in mining waste damage DNA in immune cells.

“At a meeting held in the Navajo Nation, Navajo, Crow, and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe community leaders explained they were visual learners, so translation through art would really help them understand health information,” Lewis recalled. “I had just been shown Mallery’s art while presenting some of our research to Zuni clinicians. The synchrony of those events was hard to ignore!”

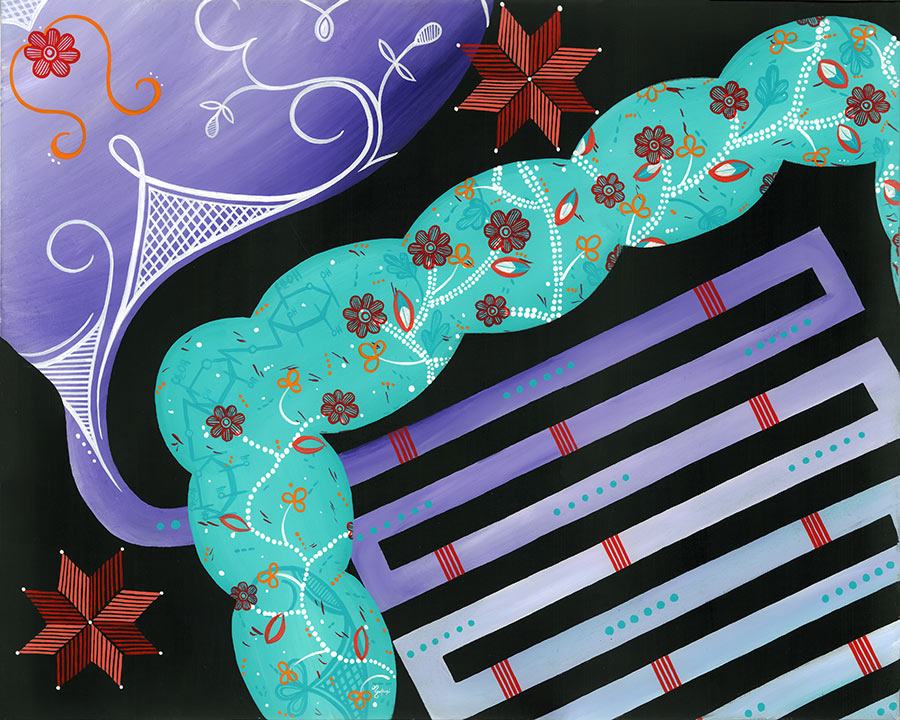

With input from the SRP team, Quetawki created a series of paintings showing how metals affect immune cell DNA. She used traditional symbols like baskets, totem animals, and bead work to convey DNA damage and repair. The designs emulate blankets from multiple Northern Plains Tribes to signify how all are connected.

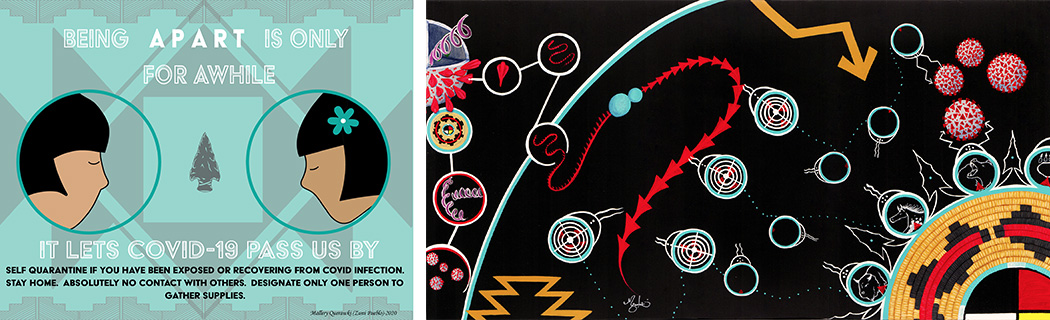

The COVID-19 pandemic brought another opportunity to communicate science through art. Quetawki noticed that Puebloans were frustrated with federal health agencies’ quarantine instructions, because the messages did not reflect Indigenous cultural needs.

“On the Zuni Pueblo, being told not to gather was a big cultural taboo,” Quetawki explained. “We do everything as a village. Tribal communities were mourning not only losing people, but also loss of ceremony and togetherness.”

To encourage acceptance of federal recommendations, Quetawki and her colleagues created culturally sensitive public service announcements, posters, and videos. She also illustrated how mRNA vaccines work, in an effort to combat vaccine hesitancy and misinformation.

Raising Cancer Awareness

Recently, Quetawki has been collaborating with the UNM Comprehensive Cancer Center to improve their outreach to the 19 Pueblo Tribes. Although the Tribes are separate, sovereign, and have distinct cultures, Quetawki is drawing on common cultural elements to create messaging around sensitive topics.

Pueblo cultures emphasize a connection between body and spirit and keeping the body whole. For Tribal members, removing tissue samples, and especially storing them for research after death, invokes spiritual harm.

Quetawki is collaborating with UNM communication faculty and students to create brochures and pamphlets, mixing art with simplified language explaining cancer research and treatments.

“Not everything in science and health can be translated into these Indigenous languages,” Quetawki explained. “That’s where art comes in: It creates a common language that bridges those gaps.”

Opportunities and Accolades

Although artists-in-residence are gradually becoming more common in environmental health, few artists work at the nexus of art, health science, and engagement with Indigenous peoples, according to Quetawki.

“What I do and how I do it are pretty unique,” Quetawki noted. “There is very little literature on communicating health science to Indigenous peoples through art — there’s nothing to cite — so my team and I are producing the literature now.”

For example, she is working on a paper for a scientific journal about communicating cancer research and treatment information to Native American communities. Quetawki has also received a pilot grant from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to expand her art and science communication activities, including recruiting and training more artists and other storytellers to share health information with other Indigenous Tribes.

“We are planning summer internships that pair artists with scientists as a way to broaden the success of our Community Environmental Health Program centers,” Lewis said.

Additionally, Quetawki’s work is attracting attention from internationally renowned institutions. On July 13, her mural of uranium extraction and remediation will be projected onto the façade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. This work appeared in the 2021-22 show, “Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology,” at the Institute of American Indian Arts Museum of Contemporary Native Arts (IAIA MoCNA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and is part of a traveling exhibit until 2024.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has also commissioned a painting depicting the gut microbiome, the collection of microorganisms living in the digestive tract.

For her part, Quetawki is excited about future opportunities to educate Indigenous peoples about environmental health.

“I want to continue helping others by using my cultural knowledge.”

Mallery Quetawki