Overview

The Gulf Coast Health Alliance: health Risks related to the Macondo Spill (GC-HARMS), a project funded by NIEHS after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill, worked with north Gulf Coast fishing communities to measure petroleum-related polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in local seafood and potential health effects over time. The GC-HARMS project consortium includes four universities and six community groups led by the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB).

Community involvement for GC-HARMS included:

- Helping to shape research questions and methods that align with community needs

- Collecting seafood samples for analysis of PAHs

- Recruiting participants, developing and translating study questionnaires, coordinating logistics, and disseminating study results

Background

In the wake of the 2010 DWH oil spill, staff at the UTMB-NIEHS Center for Environmental Toxicology conducted a survey of 26 nonprofit environmental organizations in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Texas to identify potential research priorities and gauge interest in participating in a long-term study examining health effects related to the spill. This survey led to the development of the GC-HARMS consortium and helped shape the group’s research direction and approach.

In 2011, NIEHS awarded funding to GC-HARMS as part of a DWH Research Consortia program focused on investigating the physical and mental health effects of the DWH oil spill on Gulf Coast residents. The consortium worked collaboratively with Gulf Coast fishing communities to measure seafood contamination and explore health impacts and community resiliency (how communities respond to, withstand, and recover from adverse situations) through citizen science and outreach.

Community Involvement

UTMB’s survey of 26 environmental organizations helped ensure that GC-HARMS research addressed the needs and concerns of Gulf Coast fishing communities directly impacted by the oil spill. Community partner organizations (community “hubs”), local fishermen, and their families also participated in two separate GC-HARMS data collection initiatives – a seafood sampling study to assess the PAH toxicity of locally-caught seafood, and a human health study of potential effects from exposure to PAHs through seafood consumption.

Seafood Sampling Study

UTMB scientists worked with Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN) consultant Wilma Subra to develop a sampling protocol and a citizen sampler training curriculum, incorporating feedback from local fishermen who participated in a pilot test of the sampling and training methodologies. UTMB staff and community hub coordinators also implemented a series of Fishermen’s Forums, which aimed to recruit local fishermen and raise awareness of the GC-HARMS project. More than 200 fishermen and other residents from targeted coastal communities in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama attended the Fishermen’s Forums, and 52 of the fishermen agreed to participate in the seafood sampling study.

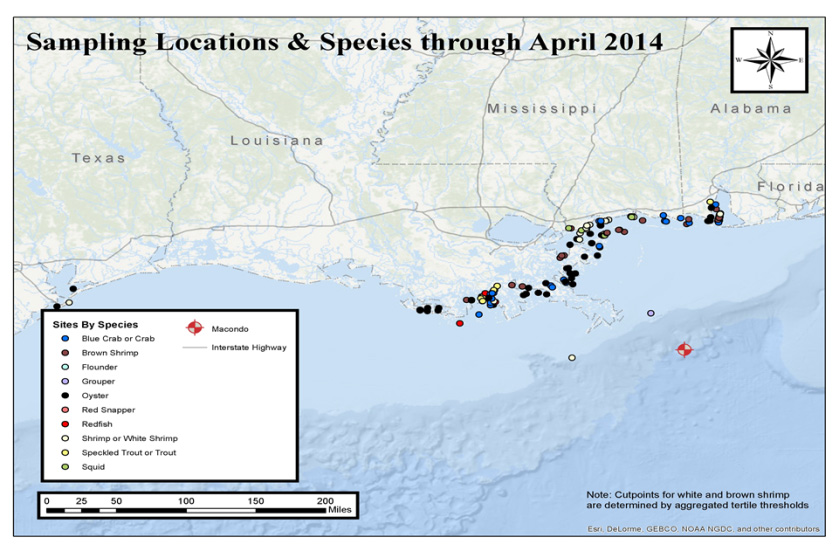

This map shows the various species collected by citizen scientist fishermen at sampling sites in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Galveston Bay, Texas, during the three-year sampling period.

(Photo courtesy of GC-HARMS website)

The fishermen’s local knowledge of consumption practices and their observations regarding changes in fish species in oil-impacted locations were integral to determining sampling site locations. In total, area fishermen collected thousands of samples of shrimp, blue crab, oysters, and a variety of finfish from 208 sites during a three-year sampling period. Only two of the samples were found to have PAH levels that exceeded the species-specific Level of Concern for PAH exposure.

Human Health Study

GC-HARMS community partners worked closely with university researchers throughout all stages of the human health study. Community hubs played an active role in selecting and recruiting participants, developing and translating study questionnaires, coordinating logistics, and disseminating the results. Four hundred individuals were randomly selected to participate in the study – 100 members from each of three fishing communities in Mississippi and Louisiana, and 100 residents from a comparison community in Galveston, Texas, not directly affected by the oil spill.

Each participant was asked to complete a survey on their health history and seafood consumption patterns annually over a three-year period, and to undergo an annual comprehensive health screening. Analyses of samples and surveys collected during the first wave of the study (during the first of three visits) suggest there is no association between plasma PAH levels and clinical health status (abnormal/normal) across the four Gulf Coast communities. Results from waves two and three of the study are forthcoming.

Outcomes

Created a user-friendly, web-based tool to communicate potential risks. The Seafood Sampling Matrix Map illustrates the scope and results of the seafood sampling study. By clicking on an individual sampling site on the map, users can access information such as sampling location coordinates, species collected, date of collection, and average PAH level detected.

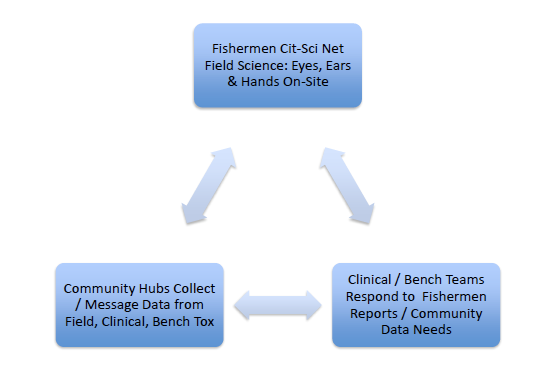

GC-HARMS fishermen, community hubs, and the science team shared information to develop sampling processes and protocols. This collaboration helped inform researchers’ understanding of local concerns and perceptions, and played a key role in translating and disseminating study findings to the target fishing communities.

(Photo courtesy of John Sullivan)

Increased environmental health literacy, improved sampling skills. GC-HARMS community outreach staff observed that the fishermen’s participation in the sampling study improved their data collection skills and increased their understanding of the association between environmental exposures and human health. This enhanced awareness of exposure-related health impacts helped disseminate the risk message throughout the target communities as fishermen discussed the health risk with their peers.

Developed fishermen’s long-term capacity to address exposures beyond the project. Participating fishermen learned relevant environmental health concepts; became proficient in carrying out U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-approved protocols for collection of seafood samples in the field; learned chain-of-custody (CoC) documentation requirements for collected samples, and how to use photography for CoC documentation; and learned the proper use of sampling and personal protective equipment. These skills enable them to engage in similar projects beyond the scope of GC-HARMS.

Highlighted health care needs, prompting near-term action in some participating communities. Survey results from the first wave of the human study revealed disparities in self-reported health symptoms and access to health care among the four Gulf Coast communities. They also identified associations between mental/emotional health and community resiliency. Some GC-HARMS community hubs have used the knowledge gained during the study to address these health disparities. One community, for example, opened a wellness center to provide mental health and stress relief services for its members.

Challenges

Gaining the trust of the local fishing communities. A significant challenge was overcoming the general lack of trust for outside organizations based on local groups’ encounters with oil companies and government organizations in the initial phases of the oil spill response. Community partners that understood the social, environmental, and health issues impacting these communities helped to overcome this obstacle. Mixed messages due to a lack of agreement between and among studies conducted by academic investigators, industry, and national, state, and local agencies engaged in risk assessment made it difficult to build trust.

Addressing concerns over the project’s impact. Some fishermen expressed concern that the project could have a negative economic impact on the community, regardless of the sampling results. To alleviate these concerns, the project team chose not to sample in certain contested fishing areas. Baseline sampling was not possible prior to the oil spill, given that the study was implemented from 2011 to 2016.

Balancing the needs and expectations of community residents and researchers. The lag time between data collection and PAH test results was concerning for participating fishermen with near-term interests in addressing the potential impacts of the oil spill on their catch. To help explain the lag time, project staff visited community hubs to explain the analytic process and discuss progress and results.

Contact

Cornelis Elferink, Ph.D.

Center for Environmental Toxicology;

University of Texas Medical Branch

[email protected]

Sharon Croisant, Ph.D.

Center for Environmental Toxicology;

University of Texas Medical Branch

[email protected]

Related Information

- GC-HARMS Home Webpage (University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston)

- New Interactive Map Displays Exposure Data Collected by Citizen Science Network

- Sullivan J, Croisant S, Subra W, Prochaska J, Howarth M, Orr M, Orr M, Curole L, Vito L, Black J, Black-Tate J, Carter Z, Gauthe S, Elferink C. 2015. Gulf Coast health alliance: health risks related to the Macondo spill – using a CBPR approach to developing tools and techniques that communicate risk and increase environmental health literacy in Gulf Coast communities affected by the DWH oil disaster [Abstract]. Presented at the American Public Health Association 143rd Annual Meeting & Expo, 31 October – 4 November 2015, Chicago IL. Available: https://apha.confex.com/apha/143am/webprogram/Paper334472.html [accessed 5 July 2017].

- Kotarba JA, Croisant SA, Elferink C, Scott LE. 2014. Collaborating with the community: the extra-territorial translational research team. J Transl Med Epidemiol 2(2):1038-1042. [Abstract]

- Sullivan J, Croisant S, Subra W, Orr M, Howarth M, Elferink C. 2014. Building and nurturing a citizen science network with fishermen and fishing communities post DWH oil disaster [Abstract]. Presented at the American Public Health Association 142nd Annual Meeting & Expo, 15 – 18 November 2014, New Orleans, LA. Available: https://apha.confex.com/apha/142am/webprogram/Paper313640.html [accessed 5 July 2017].

- Wickliffe J, Overton E, Frickel S, Howard J, Wilson M, Simon B, Echsner S, Nguyen D, Gauthe D, Blake D, Miller C, Elferink C, Ansari S, Fernando H, Trapido E, Kane A. 2014. Evaluation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using analytical methods, toxicology, and risk assessment research: seafood safety after a petroleum spill as an example. Environ Health Perspect 122(1):6-9. [Abstract]