Features

Effect of Exposures on the Immune System

Exploring how environmental contaminants affect the immune system can reveal why some people may be more susceptible to immune-related diseases and infections. NIEHS-funded Superfund Research Program (SRP) scientists study the mechanisms involved in the body's immune response to environmental stressors. Their work provides insight into how people may be affected by environmental pollutants and how the immune system responds to infectious pathogens and tumor cells.

Research descriptions are organized into these sections:

- Environmental exposures and immune response in the lung

- Investigating mechanisms of immunotoxicity

- Suppressing important immune cells in different parts of the body

Environmental Exposures and Immune Response in the Lung

At the Dartmouth College SRP Center, researchers found that arsenic exposure may alter immune response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a pathogen frequently associated with pneumonia and other respiratory diseases in the lung. Their research shows how arsenic exposure may increase the likelihood of respiratory infection and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which are associated with chronic bacterial infections and other non-malignant lung infections.

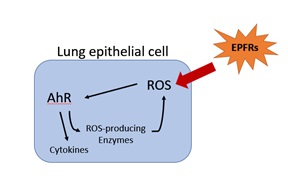

A study in human cells by the Louisiana State University (LSU) SRP Center shows how particulate matter (PM) containing environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs) activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). AhR is known to play an important role in detecting and responding to a variety of pollutants and regulating immune response. They also found that EPFRs increase cytokine production, which is important in immune system signaling. The researchers are continuing to study how EPFRs affect AhR signaling, which can lead to an altered immune response and poor respiratory health.

LSU SRP Center researchers also showed how type I interferons (IFNs) , a group of proteins that help regulate immune system activity,play a role in viral respiratory infections. They are currently studying how IFNs help regulate the rate of virus clearance and how that may be affected by environmental exposures.

Grant recipients and colleagues from the University of New Mexico (UNM) SRP Center found that particles from abandoned uranium mine dust can damage the lungs and lead to impaired phagocytosis, an immune system mechanism used to remove pathogens and cell debris. They found that both uranium and vanadium in the samples altered immune responses in the lung.

A new research project from the University of Alabama at Birmingham focuses on how heavy metals such as cadmium, arsenic, and manganese worsen lower respiratory tract infections. The team studies the involvement of lung macrophages, which have a critical role in host defense to respiratory pathogens.

Investigating Mechanisms of Immunotoxicity

Researchers are looking across species to uncover the mechanisms of immune dysregulation, including studies in mice, zebrafish, and humans.

For example, at the UNM SRP Center, grant recipients explore how uranium and arsenic affect immune system processes in both mouse and human cells. In mice , they test whether immature immune cells are particularly susceptible to metal toxicity because they lack the ability to export metals, leading to increased exposure. In human cells , they investigate whether uranium and arsenic exposure disrupt zinc binding proteins known to regulate immune responses. UNM SRP Center researchers identified nanoparticles containing uranium and other metals in mine waste located near Native American communities and are working with these communities to study whether supplemental zinc reduces immunotoxicity resulting from exposure to these metals.

At the Michigan State University (MSU) SRP Center, researchers integrate experimental and computational modeling approaches to explore how the chemical 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorediobenze-p-dioxin (TCDD) can suppress antibody production by human primary B cells. In a recent study , they found that TCDD suppresses human B cell secretion of immunoglobulin M antibodies, which are the first antibodies to appear in the response to pathogens.

At the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) SRP Center, researchers use mice to explore mechanisms involved in inflammatory responses in autoimmune diseases. They recently found that by altering the activity of REV-ERBalpha , a protein that regulates gene expression, they can manipulate the activity of T helper cells. T helper cells recognize foreign antigens and secrete substances that activate immune cells and can drive inflammatory responses. Manipulating the activity of these immune cells may provide an opportunity to reduce inflammation in autoimmune diseases.

A new research project from the North Carolina State University SRP Center uses zebrafish to understand how exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) may lead to immune suppression. They are also exploring how PFAS can affect B cell development and antibody production in mice.

Suppressing Important Immune Cells in Different Parts of the Body

A Boston University SRP Center study reported that in mice, the chemical tributyltin (TBT) affects bone marrow B cells. TBT triggered cell death and changed the microenvironment of bone marrow vital for supporting immune health. In the study, TBT exposure led to increased adipocytes, or fat cells, in bone marrow, which also occurs with aging and is associated with decreased immune response. According to the authors, increased adipocytes in bone marrow may contribute to more frequent and severe infectious diseases in the elderly, and TBT may worsen these age-related changes.

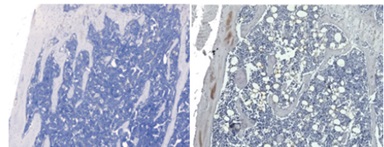

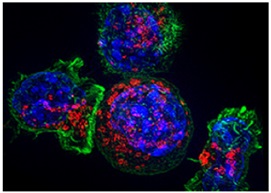

At the UCSD SRP Center , researchers study how toxicant-induced liver damage can affect immune cells in mice. For example, in a mouse study , UCSD researchers showed that chronic liver inflammation can promote cancer by suppressing immune cells that fight liver cancer development. They found that inflammation suppresses a natural defense known as immunosurveillance. This mechanism involves cells in the immune system, known as cytotoxic T cells, that guard against disease agents such as viruses, bacteria, and cancerous and precancerous cells.

Researchers at the MSU SRP Center investigate the effects of TCDD on the gut microbiome and its role in immune response. They found that feeding mice activated carbon reduced the harmful effects of TCDD on microbes in the gut without itself leading to significant changes in the gut microbiome. Activated carbon also reduced immune suppression in response to TCDD exposure.

A research team at the University of Rhode Island SRP Center explores the link between PFAS exposure profiles, immune dysfunction, and metabolic abnormalities. They are examining an established cohort of 9-year-olds from the Faroe Islands. Preliminary findings suggest PFAS alter adipokine hormones, which help regulate metabolic and immune processes, with differences by age and sex.

to Top