(Photo courtesy of Theodros Woldeyohannes)

Researchers at the University of New Mexico (UNM) Center for Native Environmental Health Equity Research study how unregulated waste disposal and burning of waste diminishes Indigenous health. By combining remote sensing, geospatial modeling, and community-engaged participatory research practices, the team aims to understand the scope, extent, and intensity of community exposure to environmental chemicals from solid waste burning.

Waste disposal is a challenge for Indigenous and rural communities throughout the U.S. Lack of resources and the rural location of many tribal lands can lead to unregulated burning of solid waste for disposal. Exposures from such burning have been linked to numerous health effects. For example, inhalation of particulate matter has been associated with increased risk of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, and microplastic contamination has been associated with oxidative stress and inflammation.

Sophisticated Spatial Modeling

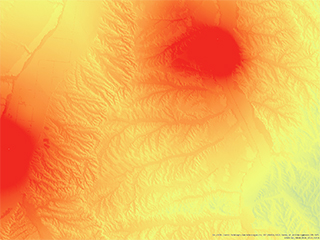

(Image courtesy of Theodros Woldeyohannes)

Past efforts to assess the extent of these exposures have been mostly questionnaire-based, in which researchers interview residents on exposure symptoms. To capture a picture of the multiple pathways of exposure, the research team —Joseph Hoover, Ph.D., and Yan Li, Ph.D., doctoral students Theodros Woldeyohannes and Daniel Beene, graduate student Christopher Girlamo, and research assistant Zhuoming Liu, M.S.— used geospatial modeling, physical modeling, and remote sensing in their approach. These techniques allow the scientists to pinpoint where and when unregulated waste burning is taking place.

So far, their models have allowed the researchers to provide high resolution imagery of local waste-burning fires in remote areas that can sometimes go undetected. The team was able to obtain enough data to estimate the frequency of such fires in partner communities over the past two decades.

According to the scientists, this is the first project to examine localized solid-waste fires in American Indigenous communities from a geospatial modeling and remote sensing perspective.

Community-based Research

Building upon long-term partnerships with communities in the Navajo Nation, Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation, and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, the researchers designed their study to address community needs and advance understanding of the scope, geography, and intensity of potential exposures.

The study also incorporates data collected by community-based team members. For example, the team developed an online form for residents to provide information about where waste is disposed of in their communities, which informed conversations to identify priority sites for environmental sampling. Silicone wristbands were adopted by the team to monitor for environmental contaminants residents may be exposed to during burn events.

Going forward, the team plans to devise new ways to identify fires that their models might miss, such as working with community partners to see if there are more records of historical fires. They also hope to create an online tool that community members can use to report fires.

“With this data, we hope to inform mitigation strategies, such as an alert system to quickly report fires so they can be put out,” Woldeyohannes said.

According to the researchers, the visual and historical evidence of fires along with new data can be used to highlight environmental health disparities. This information can, in turn, potentially inform public policy surrounding municipal waste needs in underserved communities.

To learn more about UNM’s work to assess exposures from solid waste management practices, see their Partnerships for Environmental Public Health webinar presentation.