January 04, 2022

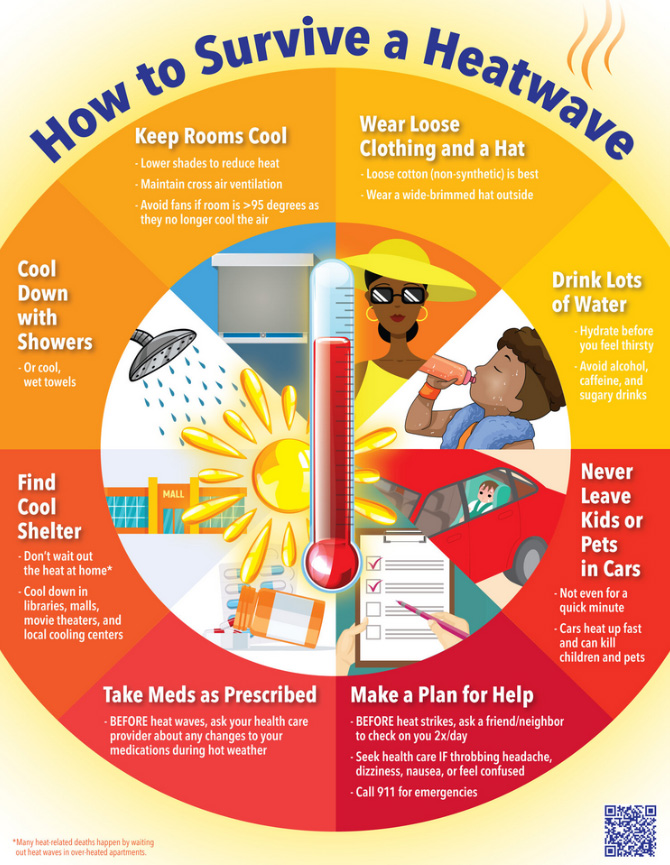

An eye-catching infographic titled “How to Survive a Heatwave,” teaches clinicians and the public about the health impacts of extreme heat and how to stay cool in hot weather. Created by psychiatrist Robin Cooper, M.D., the resource aims to reduce the health impacts of extreme heat by preparing people to manage and survive heat events before they occur. The infographic was developed through a mentored clinician award from the NIEHS-funded Environmental Research and Translation for Health (EaRTH) Center at University of California, San Francisco.

“Climate change and extreme heat can have broad and severe impacts on health,” said Cooper who co-founded the Climate Psychiatry Alliance.

In addition to causing physical problems like dehydration and heat stroke, heat can affect people’s cognition and mood, she explained.

To meet the needs of San Francisco’s non-English speaking populations, Cooper partnered with local high school students who translated the resource into Chinese. It is also available in Spanish.

Staying Cool

The tool outlines the signs and symptoms of heat-related illness, and how those signs may be different in children and the elderly. It also includes tips for keeping cool, such as staying hydrated and finding a local cooling center. These recommendations are especially important for people living in homes without air conditioning.

“Going to a cooling center or other location with air conditioning, like a library or mall, even for a few hours, can make a big difference. Many heat-related deaths occur because people think they can just wait it out in their overheated homes,” said Cooper.

Communities of color and people living in poorer neighborhoods often suffer the greatest burden of heat-related illness and death, according to Cooper. Additionally, people with limited English language skills have reduced access to information that can help them stay safe and healthy during heat events. Translating the infographic into Chinese and Spanish is one way Cooper hopes to reduce these disparities.

“The translation would not have been possible without the EaRTH Center,” said Cooper. “Funds from Center’s Integrated Health Sciences Facility Core supported translation into Spanish, which is the most prevalent non-English language in the U.S. and Bay Area. The Center was also critical in connecting me to the local high school class that took on the Chinese translation.”

Serving and Learning

“We were so honored to be involved in this project,” said Regina Liu, who teaches Chinese at Lick-Wilmerding High School in San Francisco. “It allowed us to serve our local Chinese population, especially the elderly who may not speak English, so they too can learn how to endure and safely survive a heat wave.”

By completing the project, the students fulfilled a required public service component of their curriculum. But it was about more than just checking a box.

“It was a really meaningful way to fulfill our service requirement, and our class rose to the occasion. I saw people working really hard on this project. Everyone understood that it was important,” said high school senior Ruthie Zapol.

The project went beyond boosting the students’ Chinese language skills. They also learned about the health impacts of extreme heat and even applied that new knowledge.

“Not long after the project, we had some pretty hot days in San Francisco, and I remember using what I learned from the infographic to stay cool – opening windows, taking cold showers, and even watching my younger brother for the different symptoms of heat stroke in children that we learned about,” said Zapol.

Reaching the Community

The project has become an ongoing educational and engagement experience for the students. Cooper will speak about climate change, extreme heat, and health in a February 2022 workshop at the high school, organized by Liu. The students will also write an introduction letter in Chinese that can be distributed with a paper version of the infographic. Distributing hard copies is especially important to reach members of the Chinese community who do not have access to a computer, noted Liu.

“I initially envisioned this as a tool clinicians could use to talk with their patients before a heat wave strikes,” said Cooper. “I never imagined these messages would reach youth, community groups, and non-English speaking populations, but through the EaRTH Center’s connections in the community, the project continues to grow.”