Superfund Research Program

With support from the NIEHS Superfund Research Program (SRP) and other sources, collaborators across the U.S. created the Digital Exposure Report-Back Interface (DERBI), an interactive, web-based tool that presents complex chemical exposure data in an easy-to-understand way. SRP teams use DERBI to help study participants understand their personal environmental exposures with an explanation of potential exposure sources, known and suspected health effects, and exposure reduction tips.

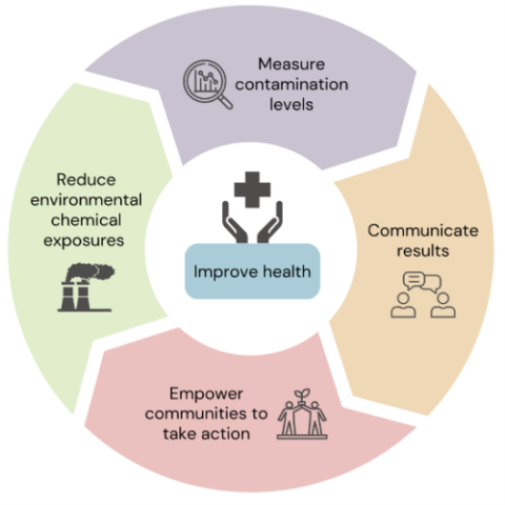

Report-back — a practice that ensures individuals and communities who are part of environmental health studies have access to their contextualized results — promotes autonomy and justice within communities. By providing information directly to people, it also empowers them to make choices that can protect their own health.

The Problem

Advances in research and technology allow scientists to detect a wide variety of contaminants in individuals’ bodies, homes, and communities, often at very low levels. This intricate, detailed data provides useful information for researchers, but poses a challenge for reporting results to participants.

In the past, environmental health researchers only reported results to individuals that were above a clinical health guideline, such as a blood lead level above the reference value established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As participants in environmental exposure studies increasingly request results, and chemical detection capabilities continue to advance, researchers are tasked with the challenge of not merely reporting but also interpreting relevant information for those people.

SRP Solutions

This tool grew from work at Silent Spring Institute to measure endocrine disrupting chemicals — substances that interfere with the body’s hormone production and function — in people’s homes as part of a breast cancer study in the early 2000s.

“Not much was known about exposures to these chemicals at the time, so we weren’t planning to return results,” said Brody. “However, our participants soon began calling to ask what we found in their samples, and we believe that people who donate their samples for research are partners in our studies and have a right to know their own results.”

Because the practice of reporting back chemical exposures without clinical guidelines was new, Brody and team began to study the best ways to communicate results by seeking input from study participants and community members.

Creating Personalized Digital Reports

The team interviewed hundreds of study participants before and after they received their results, listened as participants “thought aloud” while reading reports, and analyzed how participants navigated digital report-back formats.

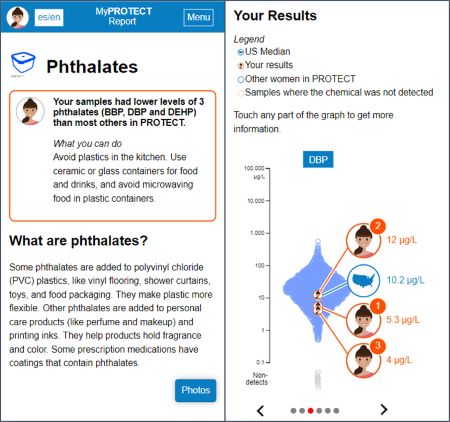

“To make results meaningful, we wanted to personalize each report to draw attention to the most notable findings, provide interpretive context, and offer comparisons to other participants in the study and across the U.S.,” Brody explained.

According to Brody, digital reports on computers or smartphones are beneficial to study participants because they can selectively navigate to the information that interests them. Digital interfaces for report-back may also be less resource-intensive for researchers to deploy and may make it easier for participants to navigate through large amounts of data.

The need for digital, user-friendly reports sparked the idea for DERBI, an online framework that takes complex chemical exposure data and presents it in a way that the average person can understand.

DERBI’s researcher dashboard also allows other investigators to do report-back in their own studies. They can access user-tested designs and contextual information from the DERBI library, which includes information about health effects, exposures sources, and strategies for exposure reduction. Content can be accessed in English and Spanish and modified to suit the particular study and community context.

SRP Commitment to Communicating Results

Forming partnerships with communities and sharing research findings in a useful and informative manner are key components of SRP. SRP Centers’ Community Engagement Cores (CEC) serve to enhance knowledge exchange and support the needs of communities impacted by environmental contamination.

DERBI is currently used by two SRP Centers — the Northeastern University Puerto Rico Testsite for Exploring Contamination Threats (PROTECT) SRP Center and the University of Rhode Island Sources, Transport, Exposure, and Effects of PFAS (STEEP) SRP Center — in addition to several other cohort studies.

PROTECT studies the relationship between environmental pollutants and adverse pregnancy outcomes. DERBI helps the team improve study recruitment and retention, provides individual exposure reduction information, and lays the groundwork for community-based participatory research projects.

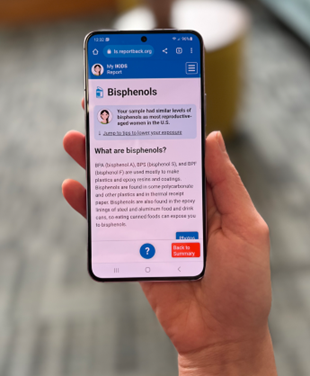

STEEP uses DERBI to communicate results of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance (PFAS) testing to private well owners in Massachusetts. The team is conducting interviews and focus groups with participants to learn more about their communication preferences to further customize reports.

Report-back benefits both participants and researchers:

- The University of Arizona SRP Center’s Metals Exposure Study in Homes involved an extensive report-back process that provided individuals and communities with the tools and information to exert control over the environmental exposures that may lead to adverse health outcomes.

- University of Arizona SRP researchers also found that report-back increases participants’ ability to understand environmental science and the scientific method, establish new networks, participate in other environmental projects, and inform cleanup standards.

- Researchers at Silent Spring Institute, the University of California, Berkeley, and PROTECT SRP Centers identified report-back benefits, including increased trust in science, retention in cohort studies, individual and community empowerment, and motivation to reduce exposures.

Advancing Health Equity

Brody explained that health inequities can stem from unequal access to scientific knowledge. Report-back provides the opportunity to learn about chemical exposures and health, and it motivates learning and health-protective action.

“In our asthma study, some of the parents told us they planned to stop using fragranced products and take other health-protective actions after they saw their results,” Brody said. “Awareness about choosing safer products is an important equity outcome because children from lower-income households are more likely to miss school due to their asthma symptoms compared to students from higher-income families.”

To be equitable, results also need to be accessible. According to Brody, the team adapted DERBI for smartphones specifically to improve access in low-income communities where phones are more often the primary access to the internet.

In addition to written summaries, DERBI uses graphs to communicate results, which draws on people’s natural ability to visualize information without relying as much on numeracy or literacy. The text is also tested for readability.

“We found that participants who were offered their personal results using DERBI spent twice as much time reading their reports as those who received only study-wide results, so the personal report-back group had more opportunity to learn about environmental health,” Brody explained. “Participants also reported positive feelings — curious, informed, interested, empowered, respected — both before and after receiving results, while negative feelings — helpless, scared, worried — remained low.”

Future Directions

Research by Silent Spring Institute and SRP collaborators contributed to the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) 2018 consensus report, which encourages report-back of research results. The push toward more disclosure is part of the larger cultural transition toward more engagement, collaboration, and transparency between investigators and research participants.

“Now that we see how much people learn from their reports, we are studying how report-back can advance environmental health literacy about endocrine disrupting chemicals specifically,” said Brody.

Future work might also explore alternative tools and platforms for reporting data, as well as whether report-back leads to behavior change that impacts health. According to Brody, cohort studies or other longer-term studies could take a deeper look at the behavior changes participants have described and provide more information about the influence of report-back on behaviors and their ultimate impact on health.