By Berkley Wood

Regions around the world are experiencing the effects of climate change differently. In Alaska, higher temperatures, later winters, earlier snow melt, and changes in vegetation are altering natural conditions to the state's fire patterns. As Alaskan wildfire seasons lengthen and intensify, exposure to wildfire smoke increases. This exposure may increase human health risks, particularly for historically disadvantaged populations, according to an NIEHS-funded study published in Environmental Research Letters. The study estimated exposure of wildfire smoke, including wildfire-related fine particulate matter across Alaska.

Wildfire smoke contains many harmful elements, including particulate matter, that can lead to serious health concerns. Particulate matter that is 2.5 microns or smaller in diameter (PM 2.5), about one-thirtieth the width of a human hair, is particularly concerning, as it can penetrate deep into the alveoli of the lungs and enter the bloodstream. Short-term effects of PM2.5 exposure include eye, nose, throat and lung irritation, coughing, sneezing, runny nose, and shortness of breath; long-term exposure can potentially cause severe respiratory and cardiovascular illness, such as chronic bronchitis, reduced lung function, lung cancer, and heart disease.

Across the U.S., particularly in the West, the frequency and intensity of wildfires have increased, resulting in higher levels of PM2.5 and more incidences of respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses. According to the National Interagency Fire Center , this year there were 48,366 fires that burned about 6.5 million acres between January 1 and October 29, compared to 47,132 that had burned about 8.4 million acres during the same period in 2020. The increased frequency of fires has strained resources, as fire departments frequently must respond to multiple fires at the same time. In Alaska, there have been 246 wildfires that have burned 95,719.9 acres across the state as of September 2021.

While physical damage from wildfires is highly visible, the health effects due to wildfire smoke are less so. Scientists at Yale University, Johns Hopkins University, Harvard University, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences investigated PM2.5 caused by wildfires in Alaska. The study found that by 2050, almost all of Alaska could experience an increase of 100% or more of PM2.5 levels due to wildfires. These findings underscore the need for more research on the health effects of exposure to wildfire smoke, and "likely presents a substantial public health burden in present day for Alaska communities," according to the study.

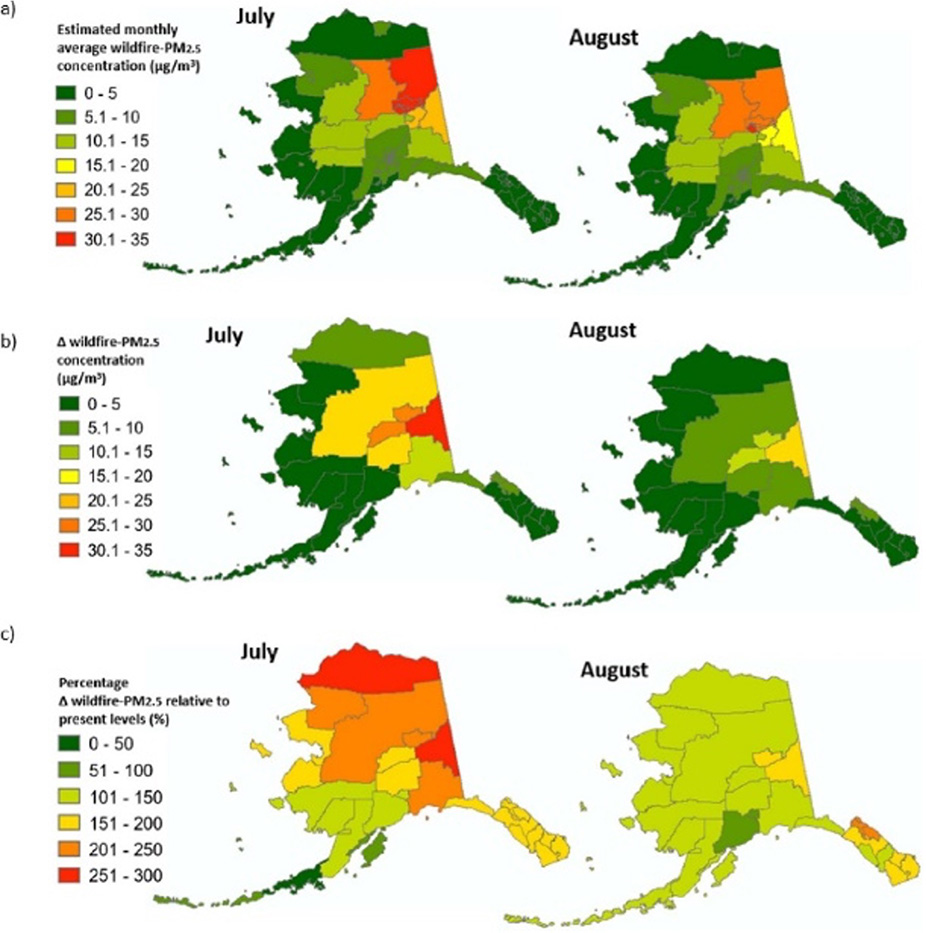

According to the article, wildfire-PM2.5 levels by borough and census tract in Alaska for July and August. (a) Wildifre-PM2.5, present day (1997 to 2010), (b) Change in wildfire-PM2.5 for 1997–2001 to 2047–2051 under climate change, (c) Percent change in wildfire-PM2.5 exposure relative under climate change (2047–2051) relative to the present-day (1997–2010). Click image to enlarge. (Photo courtesy of Environmental Research Letters)

The researchers used a fire prediction model and atmospheric transport modeling for present-day PM2.5 estimates and the GEOS-Chem global 3D Chemical Transport Model, with emissions derived from the fire prediction model, for future estimates between 2047 and 2051. They also assessed the vulnerability of various subpopulations (e.g., urbanicity, race/ethnicity, Native American tribal affiliation, occupation industry, employment and poverty status, income, education, age, and sex) using Census data and the State of Alaska's population projections. The study examined rural regions specifically given that previous studies did not investigate the difference in PM2.5 levels in rural areas that lack substantial air quality monitoring networks.

The study determined that PM2.5 levels attributable to wildfires peaked in July, and the communities most at-risk for health consequences due to higher exposure levels were in the interior of the state. Using Census data and the State of Alaska's population projections, the study assessed the vulnerability of increased exposure to wildfire smoke on various subpopulations, such as rural, urban, race and ethnicity, and Native American tribal affiliation. The study determined that these health risks will disproportionately affect urban Alaska, especially African American populations. Those most at risk were "urban residents compared to rural and remote rural residents; African-Americans/Blacks compared to other races; and Alaska Athabascans compared to other tribal affiliations," according to the study.

NIEHS Global Health Chat Podcast on Wildfires

The Global Environmental Health (GEH) program produced a podcast on the health effects from wildfires and future mitigation strategies. Three experts discussed the ways these health effects disproportionately impact marginalized groups, specifically, indigenous populations.

Emily Dickens, Ph.D., director of emergency management with the First Nations Health Authority in British Columbia, Canada, explains how these populations are especially vulnerable because of the location of the reserves.

David Bowman, Ph.D., professor of pyrogeography and fire science and director of the Fire Centre at the University of Tasmania in Australia, highlights the need to improve governance structures, planning, buildings and fuel management to address the impacts of wildfires and stabilize the climate.

Bill Tripp, director of natural resources and environmental policy for the Department of Natural Resources of the Karuk Tribe, discusses Native Americans' relationship with fire and loss of traditional food sources and access to resources when they were displaced.

Lucia Woo, master's student at Yale University and author of this study, noted that, "the 100% increased exposure represents the baseline that most regions could experience in future summers. However, in the summer, the climate is much drier and more likely to experience wildfires, and the increase in wildfire specific PM2.5 could increase to nearly 300% in certain regions. It is difficult to estimate exposure, let alone capture trends, due to a lack of air monitors in the rural regions in Alaska. Better wildfire smoke exposure characterization and more ground-based monitors across the state could create a more detailed picture of these risks."

Many other regions in the world face an increased risk of wildfires due to a changing climate, record heat, dry vegetation, and low humidity, and the need to address prevention efforts and responses to unprecedented wildfires is dire.

"It is important to also look at forest management and healthcare preparation-are the hospitals in these rural and remote areas prepared for the changes we are going to see down the road? As scientists, are we communicating the importance of limiting exposure to these risks that are already very present?" added Woo.

The NIEHS works to create awareness of wildfires in Alaska and other wildfire-prone regions in the U.S. Specifically, the NIEHS Worker Training Program provides grants and resources to protect communities and workers facing exposure to wildfires. The Partnerships for Environmental Public Education (PEPH) also produces educational materials, such as podcasts on important, current environmental issues, including wildfires and their impact on human health.