By Megan Avakian

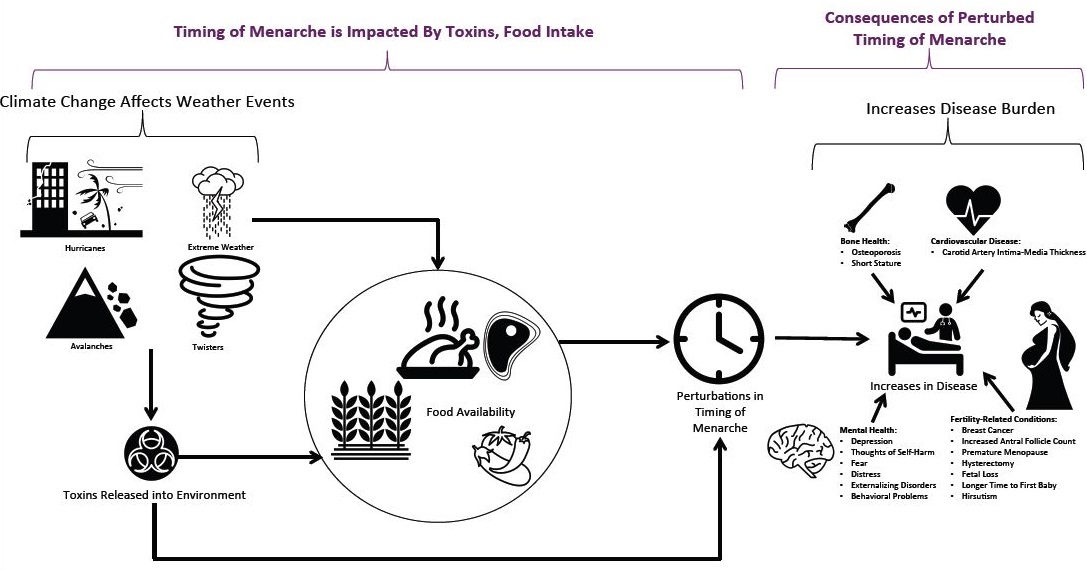

Climate change may increase disease risk for women by shifting the timing of menarche, or first menstruation, according to a systematic review published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. The paper highlights how natural disasters and extreme weather events impact environmental factors like food availability and the release of chemicals into the environment, which can cause girls to experience early or late menarche.

"The menstrual cycle affects many important functions in the body, so when menarche occurs too early or too late, it may influence disease risk and health later in life. Examining menstrual cycles and timing of menarche is going to be an important piece of understanding how climate change will affect the future health of women and all people who menstruate or have menstruated," said Silvia P. Canelon, Ph.D., who co-authored the review with Mary Regina Boland, Ph.D.

A Focus on Maternal Health

Pregnancy is another time in a woman's life when they may be particularly vulnerable to environmental exposures. NIEHS scientists work to understand how exposures during pregnancy and in the years following, called maternal health, affect the short- and long-term health of the mother.

"Pregnant women tend to worry about the effects of chemical exposures on their children, but they rarely consider the impacts on their own health," said Abee Boyles, Ph.D., a health scientist administrator at NIEHS.

Boyles was part of a team of NIEHS scientists who recently wrote a review article outlining how various environmental chemicals can harm maternal health. The article highlights the racial and ethnic disparities in environmental exposures and maternal health outcomes.

To better understand the role of the environment on maternal health, NIEHS recently awarded seven research grants focused on pregnancy as a vulnerable time period for women's health . The researchers will examine how exposure to a range of environmental pollutants may affect a mother's metabolic, heart, immune, and bone health.

Visit the Women's Health and the Environment webpage to learn more about NIEHS efforts to understand how the environment affects health conditions specific to women.

Globally, the average age for menarche is 12 years. In many industrialized countries, there has been a shift toward girls experiencing menarche earlier, but trends vary by country. The review found that climate-driven disruptions of menarche could increase disease risk for women in four key areas: mental health, fertility, cardiovascular disease, and bone health.

To better understand the factors driving shifts in timing of menarche, the scientists searched four literature databases for human population studies examining the causes or health consequences of early and late menarche. They identified 112 publications that fit their study criteria and grouped them into themes, including the environmental causes of altered menarche.

Environment Plays a Role

Nearly a third of the publications focused on the environmental causes of early or late menarche. These studies fell into two main categories - nutrition and food availability and exposure to pollutants.

Some studies found that certain nutritional factors, like high protein intake and use of soy formula, were associated with early menarche. Food insecurity and stunted growth were linked to late menarche.

In terms of pollutants, the effect on timing of menarche depended on the chemical. Studies linked exposure to lead, polychlorinated biphenyls (PBCs), and polychlorinated diphenyl ether flame retardants to late menarche. Exposure to some endocrine-disrupting chemicals and the herbicide atrazine was associated with early menarche. Depending on the type of phthalate, exposure was linked to either early or late menarche.

Disruptions in menarche were related to a range of diseases later in life. Conditions associated with early menarche included poor reproductive health, cardiovascular disease, mental health issues, and breast cancer. Girls experiencing late menarche may be at increased risk of fertility issues and osteoporosis later in life.

The Climate Connection

Climate change could impact weather events that increase the release of toxins into the environment and affect crop and food availability, which can alter timing of menarche. These shifts in menarche could increase women’s disease risk in four areas: bone health, cardiovascular disease, mental health, and fertility-related conditions. Click image to enlarge.

(Photo courtesy of Mary Regina Boland and Silvia Canelón)

"In our review of the literature, we noticed that many of the environmental factors linked to altered menarche could also be affected by climate change, so we started hypothesizing about that connection," explained Boland.

Driven by climate change, rising temperatures, droughts, and floods are expected to reduce crop and food availability around the world. Because the body requires adequate energy and nutrition to menstruate, food insecurity driven by climate change may result in delayed menarche.

A rise in the frequency and severity of hurricanes and other extreme weather events can result in increased release of chemicals into the environment. For example, hurricanes and flooding can lead to chemical and oil spills and stir up PCBs, pesticides, and other chemicals buried in river sediments, potentially exposing girls to pollutants associated with shifts in menarche.

Those who are already at risk of hunger and malnutrition, live near historically polluted areas, and cannot evacuate when a hurricane or other disaster hits, are likely to suffer the greatest burden of climate-driven effects on menarche and later disease, emphasized Boland and Canelon.

"If we prioritize the most disadvantaged, everyone benefits. A critical first step is to focus on those who bear the greatest burden of exposures and disease and work to ameliorate that burden through research and policies that support safe and healthy environments for those most affected in our communities," concluded Canelon.