Rohlman uses environmental health literacy to empower communities to protect their health.

(Photo courtesy of Oregon State University)

Diana Rohlman, Ph.D., is dedicated to communicating science to those affected by environmental pollutants, including Indigenous communities.

She received her doctorate in environmental and molecular toxicology at Oregon State University (OSU) where she studied how exposure to some chemicals can affect the immune system. As a postdoctoral trainee at the NIEHS-funded OSU Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center and OSU Environmental Health Sciences Core Center (OSU Core Center), Rohlman was inspired by the transdisciplinary nature of the programs to address complex environmental health issues.

“Under the mentorship of my undergraduate advisor, David Brown, Ph.D., I became interested in how toxicology combines chemistry, biology, and microbiology,” said Rohlman. “That interest led me to OSU where I also was very drawn to how the two Centers emphasize engaging with communities.”

Today, Rohlman directs the Community Engagement Core at the OSU Core Center and co-leads research translation projects through the OSU SRP Center.

“I’ve realized through my work with the Centers that the knowledge communities have can be equal to scientific knowledge. Furthermore, the way we talk about research is critical for increasing transparency and improving the science.”

Culturally Aware Community Engagement

The OSU Core Center and SRP Center teams engage with Indigenous and other historically underrepresented communities, government and regulatory agencies, and other stakeholders all stages of research. The centers serve as a resource hub for groups with questions and concerns about environmental contaminants in their communities. Researchers listen to stakeholder concerns to guide research questions and engage communities in research projects.

“The Centers translate research results into environmental public health knowledge that can be shared with affected communities,” said Rohlman. “We’re trying to tailor our research to be relevant to stakeholder questions and concerns while providing the science to empower people to make informed decisions for their own health and the health of the environment.”

According to Rohlman, involving communities in the early phase of studies has major benefits, from improved understanding about environmental health to better approaches for addressing community concerns and greater cultural awareness.

“Historically, Indigenous communities and other underrepresented groups have had fraught experiences with research,” Rohlman explained. “Having conversations about the historical and cultural context around data is important to make sure we’re not inadvertently doing harm. Learning the importance of different perspectives has to be embedded in the way we do community engaged research.”

The OSU SRP Center focuses on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are produced when coal, oil, wood, and tobacco are burned or when meat is cooked at a high temperature. Some tribal cultural and spiritual practices, such as burning candles and incense, also produce PAHs.

To better understand PAH exposure in the community, OSU SRP Center researchers worked with tribal partnersto initiate a community-based participatory research study using silicone wristbands, developed by OSU SRP Center researcher Kim Anderson, Ph.D.

Volunteers wore the wristbands and completed daily activity diaries about their contact with potential sources of PAHs. Then, the researchers analyzed the wristbands for 62 different PAHs. They found differences in PAH exposure among individuals and seasonal differences.

Rohlman emphasizes the importance of reporting back research results to participants in community-engaged research projects. She noted that at the end of the study, participants reported that they felt more aware about their potential exposure to PAHs from different sources and, in many cases, felt empowered to take steps to reduce their exposure. For example, participants reported using their woodstove less often for ambiance, getting their woodstove cleaned and, and selecting candles that have lower PAH emissions.

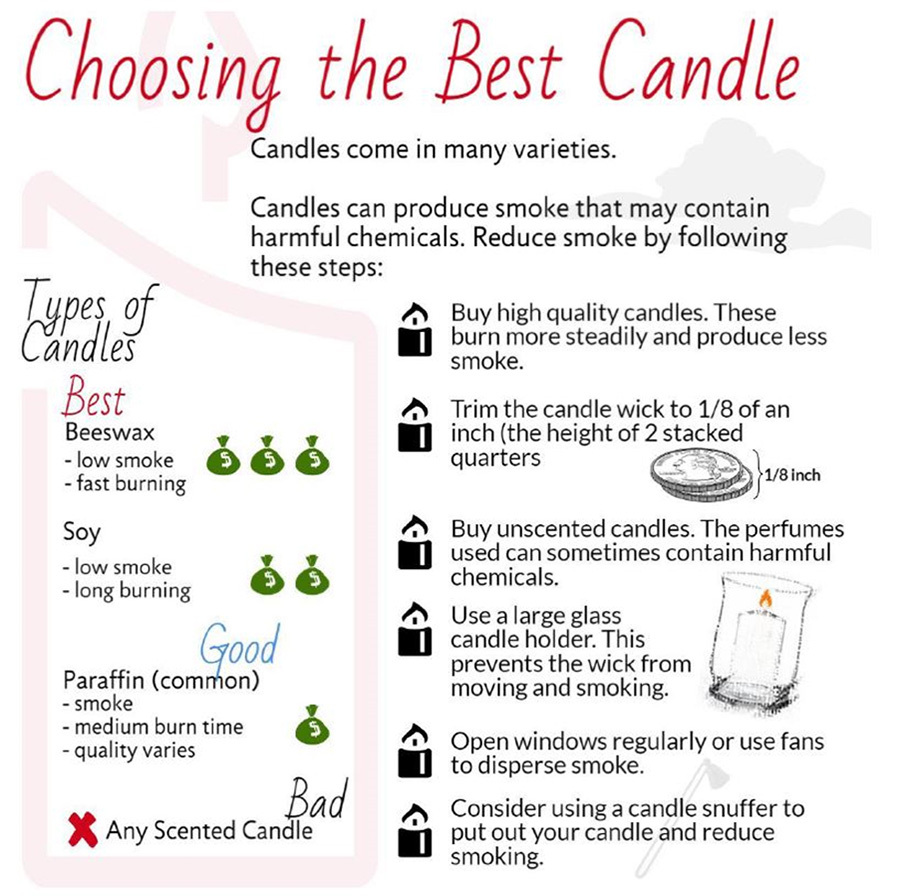

She explained that communicating ways to reduce PAH exposures from cultural or spiritual practices without casting them in a negative light was critical. For example, instead of asking tribal members to stop spiritual candle burning, OSU researchers produced an infographic for the community that illustrated how to reduce PAH emissions from candles by trimming wicks, using a candle snuffer, and purchasing soy, beeswax, or unscented candles.

“Each community may think about things differently, we have a responsibility to report findings ethically and with cultural sensitivity,” she said.

Building Environmental Health Literacy

Rohlman’s team at the OSU Core Center develops tools to build environmental health literacy among communities. For example, she collaborated with Molly Kile, Sc.D., Veronica Irvin, Ph.D., and others to develop a tool to assess environmental health literacy among domestic well owners. According to Rohlman, environmental health literacy is especially important for well owners since they must know when and how to test water for bacteria, nitrates, arsenic, and other contaminants in their drinking water.

The team adapted a health literacy tool called the Newest Vital Sign to create the Water Environmental Literacy Level Scale (WELLS). While additional refinement may be needed based on wider testing, the team determined that WELLS could be used to distinguish between participants with low versus high environmental health literacy surrounding well water. This tool can help public health practitioners identify individuals who might require additional services related to water environmental health programs, and could be broadened for other uses as well.

According to Rohlman, advancing environmental health literacy can improve health by raising awareness of potentially harmful environmental exposures and enabling communities to take action to protect their health.

“We have recognized for many years that we can empower communities with knowledge about the connection between environmental exposures and health,” Rohlman said. “As we better characterize what environmental health literacy is, we can use that to frame communication interventions and approaches to more effectively reduce risk and help people make their own decisions.”

Related Links

- Read more about Rohlman’s work at the Environmental Health Literacy and Translation Lab.

- Find out more about the OSU Core Center, the Pacific Northwest Center for Translational Environmental Health Research.

- See more infographics developed by the OSU SRP Center team.

- Read more about the OSU SRP Center research on wildfires and air quality.

- Find out more about PAHs in a Factsheet from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Learn more about the OSU team’s use of passive sampling devices.