Nestled in a corner of the NIEHS campus, the Clinical Research Unit (CRU) is an understated workhorse of translational research. The 14,000-square-foot outpatient facility offers exam rooms, pulmonary testing, imaging, metabolic assessments, and a biobank for sample storage and analysis. For NIEHS investigators, it provides the infrastructure to study human volunteers directly, ensuring that environmental health discoveries are grounded in clinical data.

“The CRU is where we bring science into contact with people,” explained Lawrence Kirschner, M.D., Ph.D., who became its medical director in 2024. “Our mission is to understand how the environment and our genes interact to affect health, and you can’t do that without studying real participants.”

A hub for translational research

The CRU supports a wide range of projects, from pediatric protocols exploring puberty and obesity, to adult studies focused on immune responses, lung health, and risk for diabetes.

Central to the CRU's operation is its extensive biobanking capability. The facility processes and stores samples from thousands of participants, including blood, serum, white blood cells, urine, hair, fingernails, toenails, and nasal cells. For specialized studies, researchers can collect cells or fluid from within the lungs through bronchoscopy, perform skin biopsies for cell culture work, and even isolate menstrual fluid for endometrial cell studies.

Collaborations with scientists conducting fundamental research drive much of this work.

“A lab might find a gene variant in mice and wonder if it affects health in people,” said Kirschner. “Through the CRU, we can bring in volunteers, collect data, and see if the same biology applies in humans. That’s translational science in action.”

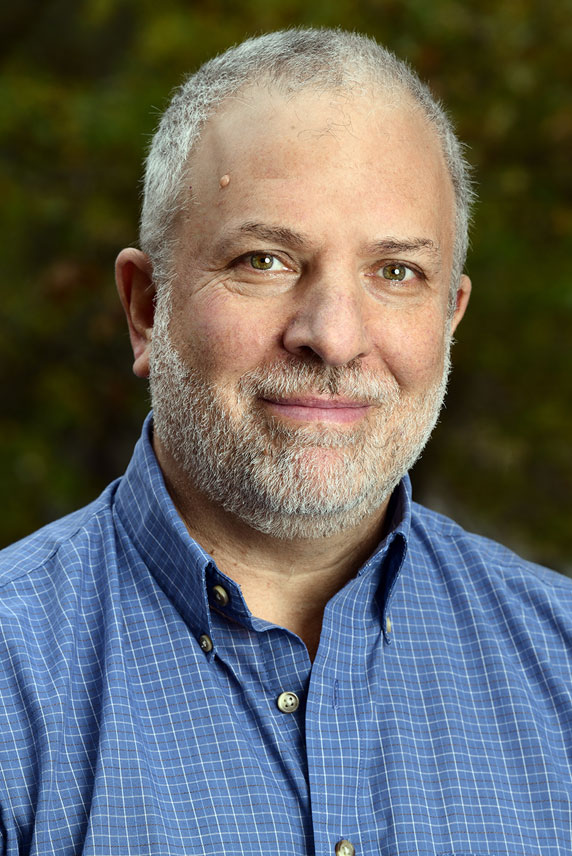

Leadership with curiosity

When Kirschner joined NIEHS, he brought with him decades of experience as an endocrinologist and clinical researcher. For example, he worked on a number of clinical trials that led to drug approvals for rare endocrine diseases and conditions, such as Cushing syndrome and acromegaly. He also has run a successful basic research lab studying the function of genes that cause inherited endocrine tumor syndromes.

“I’ve always been fascinated by how things work,” he explained. “As a kid, I was the one taking things apart and trying to put them back together — sometimes successfully, sometimes not. That same drive carried me into science: I wanted to know why cells behave the way they do, why some become cancerous, and, ultimately, why people get sick.”

Now, at the helm of the CRU at NIEHS, Kirschner is guiding a team of clinicians, nurses, and researchers who bridge laboratory findings with human health. He says that mission is tightly coupled with his own research.

Kirschner studies rare inherited tumor syndromes affecting the endocrine system, such as pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PPGL). About 40% of patients with PPGL carry a genetic mutation, yet only some develop disease.

“That tells us environment matters,” Kirschner said. “It could be smoking, high-altitude exposure, or exercise patterns. Patients want to know what they can do to reduce their risk. Answering that requires the kind of gene-environment research NIEHS is designed to do.”

A flagship initiative

Kirschner serves as co-principal investigator of the CRU’s flagship effort, the Personalized Environment and Genes Study (PEGS). This long-term project has already enrolled more than 20,000 participants, building one of the institute’s most important resources for long-term environmental health research. PEGS integrates a biobank of samples and survey data with geographic information systems mapping, enabling researchers to analyze participants' environmental exposures by ZIP code using high-density informatics.

This approach has already yielded important findings. Studies from the CRU show that living near concentrated agricultural feeding operations can negatively affect community health. Ongoing research on environmental risk factors for diabetes could also provide crucial insights for preventing what Kirschner describes as "an epidemic."

Diverse research portfolio

Beyond PEGS, the CRU currently conducts around eight to nine active studies, with additional sub-studies bringing the total to more than a dozen ongoing projects.

For example, Natalie Shaw, M.D., who leads the Pediatric Endocrinology Group at NIEHS, is conducting research on early puberty in children. Other investigators are looking at the intersection of environmental factors, immunity, and lung function. The CRU also recently launched its first Investigational New Drug trial, examining a novel treatment for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Challenges and opportunities

Kirschner acknowledges the challenges of leading clinical research today. Recruiting participants, ensuring trust, and navigating complex data all require careful stewardship.

“One of the biggest issues is public trust,” he said. “People sometimes assume researchers have hidden agendas. But we’re here to ask important questions that can improve health. Rebuilding and maintaining that trust is critical.”

At the same time, he sees unparalleled opportunity. Advances in genomic sequencing, data science, and wearable technologies allow NIEHS to explore environmental influences on health at a scale never before possible.

“It’s an incredible time to be a scientist,” he noted.

Looking ahead

Under Kirschner’s leadership, the CRU continues to expand its role as the translational engine of NIEHS. With state-of-the-art facilities, dedicated staff, and a growing portfolio of studies, it continues to connect discoveries at the bench to real-world human health.

“What gets me up in the morning,” Kirschner said, “is the chance to think about things we don’t yet understand — questions that matter to patients and communities — and to figure out how to get those answers.”

(Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)