Macrophages — the immune cells best known for defending the body against infections — may also hold the key to tackling chronic diseases. In her Sept. 2 Falk Lecture, Miriam Merad, M.D., Ph.D., explained that these versatile cells can shape outcomes in conditions ranging from aging and cancer to heart disease and neurodegeneration.

“They are an untapped source of therapeutic targets across all areas of medicine,” said Merad, a distinguished immunologist and oncologist who directs the Precision Immunology Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York.

Merad was recently named to the French knighthood for her pioneering contributions to science and medicine. Her work on macrophages has reshaped the basic understanding of the immune system and inspired strategies that harness the body’s own defenses to improve human health.

“This is just the beginning of our understanding of what these cells do,” she said.

A textbook understanding

According to Merad, inflammation is a common feature of nearly all human diseases. Central to this process are macrophages, which reside in every tissue in the body. Scientists once thought that macrophages arose mainly from circulating monocytes — short-lived immune cells that migrate to sites of injury or infection and mature into other cell types. But Merad’s research revealed that many tissue-resident macrophages are established in tissues before birth and maintained by continually renewing themselves.

“Her findings have led to the rewriting of textbooks,” said Michael Fessler, M.D., NIEHS Clinical Director and host of the lecture. “This is critically important because macrophages behave differently depending on whether they were seeded in the early embryo or derived from monocytes later in life.”

Tissue-resident macrophages can act as guardians of organ health, clearing dying cells, and limiting unnecessary inflammation. They carry out highly specialized functions, such as pruning synapses in the brain or recycling iron in the liver. By comparison, monocyte-derived macrophages tend to produce inflammatory molecules, often worsening disease.

“In heart attacks, for example, removing tissue-resident macrophages exacerbates pathology, while removing monocyte-derived macrophages improves repair,” Merad noted.

The aging immune system

In recent research, Merad has explored the link between macrophages and aging.

“With age, there is an attrition of tissue-resident macrophages, while monocyte-derived populations expand,” she said.

This shift fuels chronic inflammation and vulnerability to disease.

Her team found that older macrophages make fewer polyamines, nutrients that are essential for their renewal. Giving mice a polyamine called spermidine restored protective macrophage populations and boosted their ability to fight infections.

“When we fed old mice spermidine, we significantly improved their ability to clear lung infections,” Merad reported.

The findings align with growing interest in longevity interventions.

“There’s a big buzz about this molecule,” she added.

Cancer progression

Merad’s research has shown that the shift from protective to proinflammatory macrophage populations has contributed to a range of aging-related diseases, including cancer. Scientists have long assumed that cancer in aging adults was simply the inevitable result of mutations accumulating in cells and tissues. However, Merad said that this view is now being challenged.

Her team showed that lung cancer tumors implanted in older mice grew faster than those implanted in younger ones, not because of the tumor cells themselves but because of the aging immune system.

“Your own immune system may be a big driver of cancer progression in old age,” she said.

Older animals showed a loss of protective macrophages and an influx of monocyte-derived macrophages, as well as another cell type known as myeloid progenitors, producing high levels of inflammatory molecules called IL-1 cytokines. These inflammatory signals reshape the tumor microenvironment, promoting invasiveness and progression.

Her lab showed that blocking IL-1 reduced abnormal myeloid expansion and slowed lung tumor growth.

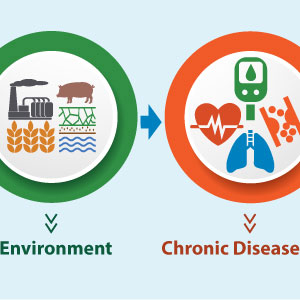

“Macrophage-driven inflammation provides the second hit that drives cancer in the context of aging or even environmental stress,” Merad said.

She believes that blocking IL-1 could help address other aging-related issues, such as cognitive decline and cardiovascular disease.

“I think we are going to see macrophages make a big impact on medicine,” Merad said.

(Marla Broadfoot, Ph.D., is a contract writer for the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.)