- Christine Marie George, Ph.D. – Using Participatory Interventions to Engage Communities and Improve Water Quality and Health

- Perry Sheffield, M.D., M.P.H. – Increasing Capacity for Children’s Environmental Health in a Changing Climate

- Michele Marcus, Ph.D. – Lived Experiences Document and Validate a Community’s Struggle

- Juan Parras – Organizing Community Voices to Achieve Environmental Equity, Justice, and Resilience

- Elaine Symanski, Ph.D. – Collaborating with Communities to Address Environmental Health Disparities

- Diana Rohlman, Ph.D. – Innovating Environmental Health Communication

- Mary Turyk, Ph.D. – Promoting Healthy Fish Consumption in Asian Communities

- Luz Huntington-Moskos, Ph.D. – Partnering With Youth to Support Environmental Health Literacy in the Next Generation

- Natalie Sampson, Ph.D. – Building Capacity in Community Science to Address Environmental Inequalities

- Mindy Richlen, Ph.D. – Developing Innovative Community Engagement on Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs)

- Angela Reyes – Addressing Air Pollution Effects With Multidisciplinary Matchups

- Montgomery Proffit – Making an Impact Through Employment Opportunities

Christine Marie George, Ph.D. – Using Participatory Interventions to Engage Communities and Improve Water Quality and Health

December 20, 2021

Christine Marie George, Ph.D., is committed to improving water quality and health in disadvantaged communities.

George first became interested in public health as an undergraduate at Stanford University, where she partnered with communities in the Navajo Nation to investigate the impact of abandoned uranium mines on health.

Today, as an epidemiologist and environmental engineer at Johns Hopkins University, she continues her work engaging communities, and uses participatory interventions to reduce exposures to environmental exposures such as arsenic in drinking water.

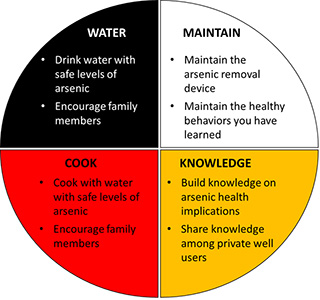

“Our approach allows communities to design and implement interventions to improve their health,” George said. “It is crucial that the community be engaged throughout the entire process and feel ownership of the intervention.”

Engaging Communities, Building Local Capacity

George has a long history of engaging communities in health-driven interventions.

For more than 14 years, she has worked with communities in Bangladesh to reduce environmental exposures in drinking water.

In one study, George and her team found that household education about arsenic helped increase the demand for water testing in rural Bangladesh. They also found that training community members to deliver arsenic education and perform water testing proved to be an effective, low-cost approach to reduce exposure. Overall, these interventions built local capacity, promoted community participation, and encouraged Bangladeshi households to use safer drinking water.

Developing an Intervention That Meets Community Needs

As co-director of the Strong Heart Water Study with Ana Navas-Acien, M.D., Ph.D., George is examining the effectiveness of a participatory intervention to reduce arsenic exposure among private well users in American Indian Nations in the Great Plains. The study, which started in 2015, is the first randomized controlled trial of an arsenic filter intervention for communities in the U.S.

Prior to launching the trial, George partnered with the community to determine what type of intervention would help meet their needs and be used by households.

“Just because a technology has the highest efficacy in terms of arsenic removal doesn’t mean it is the one that people will actually use,” George said.

The community stressed the importance of maintaining the aesthetic qualities of their water, such as taste and temperature. Given this feedback, the team decided a specialized, point-of-use water filter in the kitchen faucet would work best. The specialized filter binds to and removes arsenic through adsorption. George said other filters that use reverse osmosis may be more effective in removing total arsenic from water, but they often change the taste.

In a pilot study to assess water quality, George and her team found that the specialized water filter was effective in decreasing arsenic levels below the limit of detection in water samples collected nine months after installation, while also being highly acceptable to the households using it.

According to George, combining home visits, video testimonials, and phone calls to promote use of the filter was an effective approach.

Ensuring a Sustainable Approach

To ensure that the Strong Heart Water Study intervention is sustainable and continues to have benefits over time, George and her team also partner with tribal government and elders in the community.

Elders are highly respected within tribal communities, so obtaining their trust and buy-in is critical. Video testimonials from elders were particularly effective.

“In the video testimonials, the elders talked about arsenic, its health impacts, and the need for people to protect themselves,” George said. “This was much more valuable than a video from me or another researcher because the information was coming from someone in the community.”

The Tribal Housing Authority partnered with the Indian Health Service to install the filters in participating households.

“We realized early on that the intervention needed to be integrated into existing tribal programs,” George said. “So even after research funding is over, the Tribal Housing Authority can continue to install filters in partnership with the Indian Health Service.”

As George and her team move forward to analyze data from the intervention trial, they will continue engaging these stakeholders. They hope that their research can serve as model for other scientists and authorities, including the Indian Health Service, to tailor interventions to support American Indian communities in other regions across the country.

Perry Sheffield, M.D., M.P.H. – Increasing Capacity for Children’s Environmental Health in a Changing Climate

November 12, 2021

Perry Sheffield, M.D., M.P.H., is a trailblazer in children’s environmental health.

Sheffield was inspired to become a doctor at a young age. Her grandmother graduated from a Canadian medical school at a time when few women had done so. Her mother taught science for a school where Sheffield helped to take care of farm animals. These early experiences led to her to pursue medicine after studying environmental health as an undergraduate.

“I didn’t know that it was an option to combine environmental health and pediatrics until well into my training at Johns Hopkins,” she said. “Our team at Mount Sinai is highlighting this possibility for people early in their careers and opening this exciting field to more trainees.”

Responding to Clinical Concerns with Research

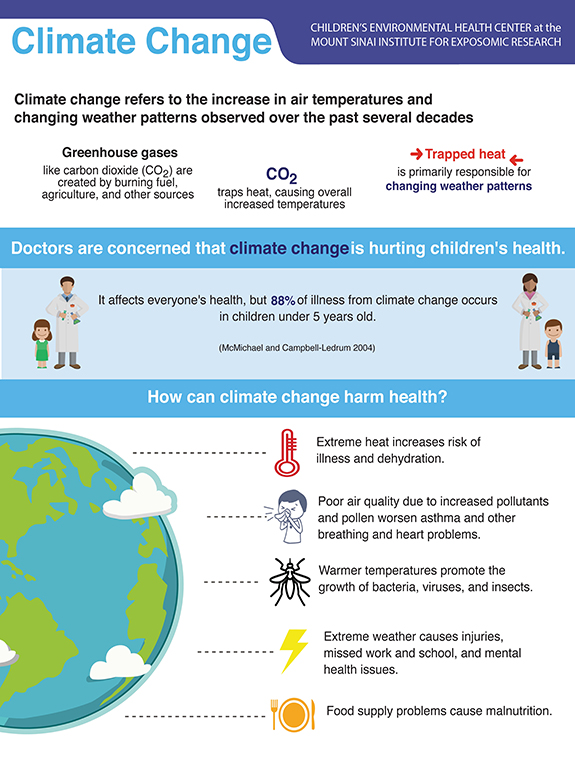

Sheffield is interested in how heat, extreme weather, and air pollution affect children’s health. At the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, she leads an NIEHS-funded study to explore just that. The study investigates children’s susceptibility to heat and health outcomes, such as injuries, that at first may seem unconnected.

“Thankfully, we don’t typically see an increase in children’s mortality during extreme heat events because of social protections,” she said. “But there may be less obvious effects that drive more children to go to the hospital, and I’m interested in teasing that out.”

For example, the team reported that higher temperatures were associated with increased risk of emergency department visits and hospitalizations among children from 0 to 18 years.

“There is also an interesting body of work about how heat affects adult behavior, including violence,” she explained. “We’re exploring if there are similarities among children or if heat-related behavioral changes among young people are different.”

Prescriptions for Prevention Put Environmental Health in the Spotlight

As part of the Community Engagement Core (CEC) of the NIEHS-funded Transdisciplinary Center on Early Environmental Exposures at Mount Sinai, Sheffield and colleagues worked with community partners to launch Prescriptions for Prevention. Covering a wide variety of topics, these innovative tools incorporate environmental health into clinical visits.

“The screening component streamlines the time it takes healthcare providers to ask about environmental exposures, such as mold, secondhand smoke, or other contaminants, and act on them to protect people’s health,” Sheffield shared. “There are also Prescriptions for Prevention related to climate change and heat that focus on babies, pregnant women, and adolescents.”

"This tool helps connect the dots among researchers, clinicians, and community partners by incorporating environmental health into routine pediatric care and enabling health care providers to refer patients to necessary services,” she explained. “We want to empower parents to take meaningful action to reduce their children’s environmental exposures.”

Promoting Environmental Justice

According to Sheffield, a key driver of her work with the CEC, co-led by Maida Galvez, M.D., and Carol Horowitz, M.D., is addressing environmental health inequities, which can be exacerbated by climate change. Luz Guel is the CEC’s Director of Anti-Racism Initiatives and Environmental Justice Partnerships.

“We have the opportunity to work with multidisciplinary researchers that are passionate about centering the health and wellness of marginalized communities,” said Guel.

Guel described how the CEC is working on a publication in collaboration with community members concerned with air quality about solving social and environmental problems through research.

“The concept we’re developing in the publication was inspired by the work of Sacoby Wilson, Ph.D., and aims to include structural racism in a framework for environmental health,” Guel explained. “This framework can help answer the question of how to liberate communities experiencing environmental injustices.”

According to Sheffield, undoing environmental injustices and addressing the health impacts of climate change are challenges, but she remains optimistic. She recently co-authored an article on the intersection of pediatrics, climate change, and structural racism.

“These are problems that were created by people and so people also have the power to address them,” she said. “Environmental health researchers can be part of this change by providing policymakers with the information needed to make health-protective decisions and advance environmental justice.”

Related Links

- Visit the Transdisciplinary Center on Early Environmental Exposures to learn more about the Prescriptions for Prevention and view fact sheets on environmental exposures.

- Read about the intersection of pediatrics, climate change, and structural racism.

- Learn more about how the New York State Centers of Excellence in Children’s Environmental Health developed.

- Read about the differences in heat risk among young children Sheffield and her colleagues found in this NIEHS-funded study.

Michele Marcus, Ph.D. – Lived Experiences Document and Validate a Community’s Struggle

October 21, 2021

Michele Marcus, Ph.D., has over 20 years of experience conducting large studies in human populations to understand the health consequences of factors like psychosocial stress and exposure to pollutants.

After receiving graduate degrees in epidemiology at Columbia University, Marcus went to work at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. There, she witnessed the effects that contaminants, such as asbestos, lead, and organic solvents, had on worker’s health.

“An important part of my fundamental training in epidemiology was understanding that the environment was such a critical component of people’s health,” she reflected. “Working at Mount Sinai moved beyond just analyzing data. Meeting workers impacted by their on-the-job exposures changed my perspective to a personal one.”

Agricultural Disaster Leads to Lifelong Study

Now at Emory University, Marcus leads the NIEHS-funded Michigan PBB study, which has followed multiple generations enrolled in the Michigan PBB Registry for over 40 years.

“In 1973, livestock feed supplement was accidentally replaced with a fire retardant, leading to widespread contamination of meat and dairy products with PBBs,” explained Marcus. “Over 4,000 individuals with high likelihood of exposure were enrolled into the registry.”

PBBs are a class of chemicals suspected to disrupt endocrine function. The endocrine system regulates hormone processes in the human body, such as development of the brain and the growth and function of the reproductive system.

Marcus' mentors at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Irving Selikoff, M.D., and Philip Landrigan, M.D., led the initial studies of the PBB cohort and helped establish the registry in the late 1970s.

“I became involved with the cohort in the early 1990s when evidence about the long-term impacts of exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals was growing,” explained Marcus. “Unfortunately, we have documented impacts to the grandchildren of those exposed, which is why it is so important that we continue to work closely with the community to address their concerns moving forward.”

When the state health department no longer had the resources to continue data management and outreach efforts, Marcus and her team stepped in. With the help of Melanie Pearson, Ph.D., co-director of the Community Engagement Core in the NIEHS-funded HERCULES Exposome Research Center at Emory University, they began hosting community meetings and met study participants face-to-face.

“In 2011 when we held our first community meeting, many people were very angry and felt abandoned because researchers who collected data never came back to talk to them,” said Marcus. “We asked community members to be our advisors and partners so we could make our continuation of the work meaningful to them and responsive to their concerns.”

Documenting Lived Experiences

“Our community partners guide our research,” said Marcus. “Their input helped us identify the need for listening and documenting their stories to understand the human toll that this incident had on their lives and to validate their experiences.”

They teamed up with Brittany Bayless Fremion, Ph.D., a historian at Central Michigan University, to collect oral histories from community members about their lived experiences and environmental exposures.

The research team is now analyzing those stories to better understand how people perceive environmental risks. After the recordings are transcribed and reviewed by participants, they will be donated to the Museum of Cultural and Natural History at Central Michigan University for use by educators, researchers, and community members.

Sharing Information

Input from the community has been used inform public health action. For example, in 2019, project collaborators hosted a legislative event to share the lessons learned from the PBB accident and ongoing community needs to inform state efforts in response to contamination.

After hosting the community meetings, the team realized that local doctors were unaware of the long-term health effects of exposure to PBBs, such as thyroid problems, breast cancer, and fertility issues.

“We found that 60% of the people tested still had elevated PBB levels 40 years later,” said Marcus. “Community members told us that when they asked if certain health issues could be connected to PBB exposure, their physicians did not have any answers for them. So, we developed a clinician information sheet, which people can take to their doctors.”

Sustained Support Continues to Address Community Needs

Marcus stressed the importance of funding from NIEHS to address community concerns. She explained that following an interview she had with a local television station in Michigan, community members contacted her to express their concerns.

“Chemical workers and nearby residents had been sidelined from the Michigan PBB study in 1990 because they were exposed to multiple different chemicals,” said Marcus. “We met with multiple community leaders who expressed their strong desire to be brought back into the study, so we applied for supplemental NIEHS funding to evaluate their exposure to PBB and other chemicals and used metabolomic methods as part of our ongoing research on the cohort.”

Confirming the long-term health effects reported by community members in the PBB study, Marcus and collaborator Alicia Smith, Ph.D., also recently documented the underlying mechanism by which PBB exposure can lead to hormone-related health outcomes.

Funding from NIEHS allowed Marcus and team to continue the Michigan PBB Registry study and their engagement with study participants. They hold partner and community meetings, respond to inquiries from the community and clinicians, and regularly update their website and social media. They are also developing an education course for healthcare providers, policymakers, and citizens to increase local capacity to address exposure concerns in this underserved, mostly rural, population.

“We knew early on how meaningful this work would be,” said Marcus. “The community deserves to know what is happening and how to protect their health. This support will allow us to continue the work we started and create new tools to share research results with our stakeholders.”

Juan Parras – Organizing Community Voices to Achieve Environmental Equity, Justice, and Resilience

September 29, 2021

Juan Parras is dedicated to fighting for environmental and social justice. As the executive director and founder of the Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (t.e.j.a.s.), a community partner of the NIEHS Superfund Research Program Centers at Texas A&M University and the Baylor College of Medicine, Parras strives to achieve equity, justice, and resilience for marginalized communities.

“Everyone, regardless of race or income, is entitled to live, work, and play in a clean environment,” he said.

Creating Environmentally Healthy Communities

As an undergraduate student at the University of Houston, Parras helped organize workers through the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees to promote better health and safety standards.

He later used these skills to support a predominantly African American community in Convent, Louisiana, who were opposed to the construction of a polyvinyl chloride plant in the area.

“That was my first environmental justice win,” Parras noted. “With the help of community members, local and national organizations, and universities in the area we were able to support the community in having their voices heard.”

Upon return to his home state of Texas, Parras became involved in another environmental justice case surrounding the placement of a new high school in a predominately Hispanic community.

“What caught my attention was that less than a quarter of a mile from the high school’s site, there were three huge sources of air pollution – two petrochemicals and a rubber plant,” Parras remembered. “We did not win this fight, but this is how the idea of starting our own environmental nonprofit to advocate for minority communities was born,” said Parras. “At t.e.j.a.s., our goal is to provide community members with the resources to advocate for and create sustainable and environmentally healthy communities.”

Addressing Environmental Issues at the Local and Federal Level

Extreme weather events, like hurricanes and flooding, can exacerbate the issues environmental justice communities face. After hurricane Harvey made landfall in 2017, t.e.j.a.s. leadership and Texas A&M SRP Center researchers mobilized to evaluate any potential human health hazards, including air pollution, in Houston.

“There are major petrochemical and industrial facilities surrounding our communities in the greater Houston area. This, coupled with poor infrastructure and extreme weather events that are increasing in frequency, can be very destructive and raise the level of toxic air pollutants in our communities,” said Parras.

T.e.j.a.s. organized public meetings with community members, state officials, and local nonprofits to understand community needs and discuss future projects to build community resilience regarding man-made hazards. As a result of these efforts, 16 benzene air quality monitors were placed along the northern border of Manchester, one of the most affected neighborhoods in East Houston.

When Hurricane Laura hit Texas in 2020, Texas A&M SRP Center researcher and t.ej.a.s came together again to discuss ongoing collaborations to better understand the effects of extreme weather events on environmental justice communities in Houston.

“Our partnerships with researchers from local universities have helped us obtain valuable scientific evidence that there are toxic air pollutants in our communities, but there is more to do,” Parras emphasized. “We need to translate research to inform policies that will protect our people and protect their well-being.”

On March 29, the White House announced the members of the new White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. Parras was selected as one of the 26 individuals tasked with providing advice and recommendations on how to address current and historic environmental injustices to the Chair of the Council on Environmental Quality and the White House Environmental Justice Interagency Council.

“This is an impressive group of people and each member selected has been working to confront environmental injustices all over the U.S. for decades,” Parras noted. “Together we are in a great position to ensure that marginalized and polluted communities have greater input on federal policies and decisions affecting all of us.”

Elaine Symanski, Ph.D. – Collaborating with Communities to Address Environmental Health Disparities

July 23, 2021

Symanski directs the NIEHS funded Maternal and Infant Environmental Health Riskscape Research Center and serves as deputy director of the NIEHS-funded Gulf Coast Center for Precision Environmental Health.

(Photo courtesy of Baylor College of Medicine)

Elaine Symanski, Ph.D., of the Baylor College of Medicine, uses community-based research to understand and address health risks associated with exposure to air pollution.

After earning her doctorate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, she moved to Houston where her research evolved to studying human populations using engaged approaches in environmental justice communities.

“Houston is unusual in that we have no zoning,” she explained. “This means that we often have industries that are right next door to neighborhoods, and these neighborhoods are often predominantly poor, and predominantly minority. I became interested in better understanding the impact of chemical and non-chemical stressors on health among individuals living in these neighborhoods and on how to arrive at solutions to address them.”

Learning from Community Members

Symanski recalled one of her first projects in this arena focused on exploring health disparities among Mexican Americans exposed to chemical (air pollution) and non-chemical (psychosocial) stressors.

"Collaborating closely with Maria Jimenez, a community organizer, had a large impact on me,” Symanski remembered. “Maria spent over 40 years promoting social justice issues relevant to the Hispanic/Latinx community. She taught me about equity, diversity, and inclusion, and helped me to better understand some of the injustices we were trying to confront through our research."

This experience fueled Symanski’s passion for involving communities in environmental health research to make it more culturally relevant and getting their buy-in for potential solutions.

“I've learned that it is critical to reach out to communities and meaningfully involve them to promote racial, social, and climate justice,” she said.

Building Trust

Dr. Symanski (left) moderates a community forum (November 2018) for the Metal Air Pollution Partnership Solutions (MAPPS) project. Community members, academics, public health officials, and industry partners are present.

(Photo courtesy of Heyreoun An Han)

Symanski has observed a common barrier to addressing community health concerns is a lack of trust among residents, researchers, governmental officials, and industry stakeholders.

She explained how the Metal Air Pollution Partnership Solutions project, funded by the NIEHS Research to Action Program, brought community members and metal recyclers to the table to work together.

"Creating space for all members to voice their concerns and actively participate in the research process allowed them to build trust and work towards a common goal," she noted. "It was rewarding to see two groups often viewed as being at odds come together in solidarity to work towards solutions.”

“Using results from air monitoring, risk assessments, and a community survey, we developed a public health action plan together, which ultimately led to industry partners taking actions in the scrap yards to reduce emissions,” says Symanski.

Promoting Maternal and Infant Health Now and in the Future

Community members report back on their photovoice projects during their environmental health leadership training as part of the MAPPS project (July 2019). Photovoice is a participatory research method that uses community photographs of environmental concerns to identify issues and stimulate discussion.

(Photo courtesy of Heyreoun An Han)

Today, Symanski continues her community-engaged research as director of the Maternal and Infant Environmental Health Riskscape Research (MIEHR) Center, funded by NIEHS, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. “Riskscapes” are the collective exposures from the biological, physical, and social environments that affect maternal and infant health.

“There’s probably no more important group to focus on than mothers and their children,” she stressed. “When you improve mothers’ and family health, you are really improving the health of the entire community.”

Symanski envisions the MIEHR Center as the anchor around which environmental health disparities research in Houston and the surrounding areas is conducted. She hopes to gain new insights on the lived experiences of those affected by environmental pollution to better inform research strategies and communication approaches.

“Through our conversations with the community, we have heard that Black mothers want to talk to us about their experiences, particularly about giving birth. So, we’re developing a forum for mothers to talk to us about their experiences and concerns,” says Symanski.

Making sure this type of research continues to address emerging environmental health problems is important to Symanski. One important aspect of this is training early-stage investigators.

Dr. Symanski emphasized, “The mentoring we give the next generation of researchers, clinicians, and policymakers will help expand the focus of their work to include environmental health and insights from the environmental justice movement.”

Related Links

- Learn more about the Center for Precision Environmental Health and research on maternal and infant environmental health riskscapes.

- Read about the legacy of Maria Jimenez, Symanski’s collaborator and environmental justice researcher and advocate.

- Learn more about the environmental health and pregnancy disparities research from the Baylor MIEHR Center.

Diana Rohlman, Ph.D. – Innovating Environmental Health Communication

June 22, 2021

Rohlman uses environmental health literacy to empower communities to protect their health.

(Photo courtesy of Oregon State University)

Diana Rohlman, Ph.D., is dedicated to communicating science to those affected by environmental pollutants, including Indigenous communities.

She received her doctorate in environmental and molecular toxicology at Oregon State University (OSU) where she studied how exposure to some chemicals can affect the immune system. As a postdoctoral trainee at the NIEHS-funded OSU Superfund Research Program (SRP) Center and OSU Environmental Health Sciences Core Center (OSU Core Center), Rohlman was inspired by the transdisciplinary nature of the programs to address complex environmental health issues.

“Under the mentorship of my undergraduate advisor, David Brown, Ph.D., I became interested in how toxicology combines chemistry, biology, and microbiology,” said Rohlman. “That interest led me to OSU where I also was very drawn to how the two Centers emphasize engaging with communities.”

Today, Rohlman directs the Community Engagement Core at the OSU Core Center and co-leads research translation projects through the OSU SRP Center.

“I’ve realized through my work with the Centers that the knowledge communities have can be equal to scientific knowledge. Furthermore, the way we talk about research is critical for increasing transparency and improving the science.”

Culturally Aware Community Engagement

The OSU Core Center and SRP Center teams engage with Indigenous and other historically underrepresented communities, government and regulatory agencies, and other stakeholders all stages of research. The centers serve as a resource hub for groups with questions and concerns about environmental contaminants in their communities. Researchers listen to stakeholder concerns to guide research questions and engage communities in research projects.

“The Centers translate research results into environmental public health knowledge that can be shared with affected communities,” said Rohlman. “We’re trying to tailor our research to be relevant to stakeholder questions and concerns while providing the science to empower people to make informed decisions for their own health and the health of the environment.”

According to Rohlman, involving communities in the early phase of studies has major benefits, from improved understanding about environmental health to better approaches for addressing community concerns and greater cultural awareness.

“Historically, Indigenous communities and other underrepresented groups have had fraught experiences with research,” Rohlman explained. “Having conversations about the historical and cultural context around data is important to make sure we’re not inadvertently doing harm. Learning the importance of different perspectives has to be embedded in the way we do community engaged research.”

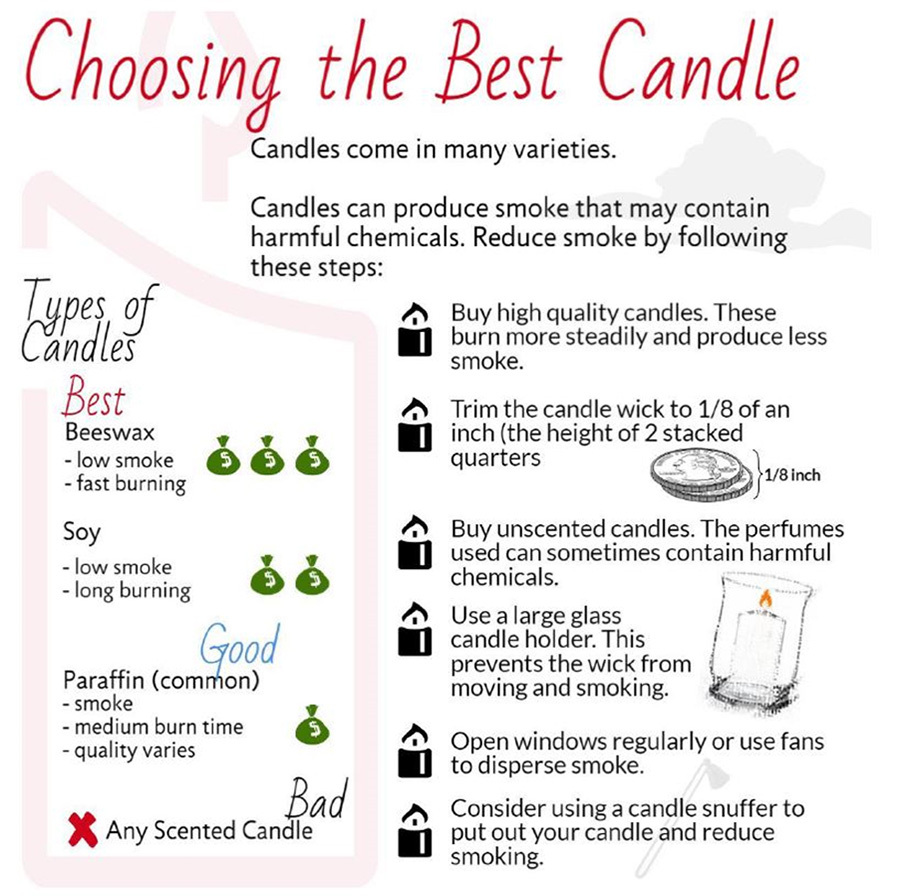

The OSU SRP Center focuses on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are produced when coal, oil, wood, and tobacco are burned or when meat is cooked at a high temperature. Some tribal cultural and spiritual practices, such as burning candles and incense, also produce PAHs.

To better understand PAH exposure in the community, OSU SRP Center researchers worked with tribal partnersto initiate a community-based participatory research study using silicone wristbands, developed by OSU SRP Center researcher Kim Anderson, Ph.D.

Volunteers wore the wristbands and completed daily activity diaries about their contact with potential sources of PAHs. Then, the researchers analyzed the wristbands for 62 different PAHs. They found differences in PAH exposure among individuals and seasonal differences.

Rohlman emphasizes the importance of reporting back research results to participants in community-engaged research projects. She noted that at the end of the study, participants reported that they felt more aware about their potential exposure to PAHs from different sources and, in many cases, felt empowered to take steps to reduce their exposure. For example, participants reported using their woodstove less often for ambiance, getting their woodstove cleaned and, and selecting candles that have lower PAH emissions.

She explained that communicating ways to reduce PAH exposures from cultural or spiritual practices without casting them in a negative light was critical. For example, instead of asking tribal members to stop spiritual candle burning, OSU researchers produced an infographic for the community that illustrated how to reduce PAH emissions from candles by trimming wicks, using a candle snuffer, and purchasing soy, beeswax, or unscented candles.

“Each community may think about things differently, we have a responsibility to report findings ethically and with cultural sensitivity,” she said.

Building Environmental Health Literacy

Rohlman’s team at the OSU Core Center develops tools to build environmental health literacy among communities. For example, she collaborated with Molly Kile, Sc.D., Veronica Irvin, Ph.D., and others to develop a tool to assess environmental health literacy among domestic well owners. According to Rohlman, environmental health literacy is especially important for well owners since they must know when and how to test water for bacteria, nitrates, arsenic, and other contaminants in their drinking water.

The team adapted a health literacy tool called the Newest Vital Sign to create the Water Environmental Literacy Level Scale (WELLS). While additional refinement may be needed based on wider testing, the team determined that WELLS could be used to distinguish between participants with low versus high environmental health literacy surrounding well water. This tool can help public health practitioners identify individuals who might require additional services related to water environmental health programs, and could be broadened for other uses as well.

According to Rohlman, advancing environmental health literacy can improve health by raising awareness of potentially harmful environmental exposures and enabling communities to take action to protect their health.

“We have recognized for many years that we can empower communities with knowledge about the connection between environmental exposures and health,” Rohlman said. “As we better characterize what environmental health literacy is, we can use that to frame communication interventions and approaches to more effectively reduce risk and help people make their own decisions.”

Related Links

- Read more about Rohlman’s work at the Environmental Health Literacy and Translation Lab.

- Find out more about the OSU Core Center, the Pacific Northwest Center for Translational Environmental Health Research.

- See more infographics developed by the OSU SRP Center team.

- Read more about the OSU SRP Center research on wildfires and air quality.

- Find out more about PAHs in a Factsheet from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Learn more about the OSU team’s use of passive sampling devices.

Mary Turyk, Ph.D. – Promoting Healthy Fish Consumption in Asian Communities

May 13, 2021

Turyk is a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

(Photo courtesy of Mary Turyk)

Mary Turyk, Ph.D., co-director of the Integrative Health Science Facility Core for the NIEHS-funded ChicAgo Center for Health and the Environment, is passionate about improving public health by studying dietary habits related to seafood and fish consumption.

Although seafood consumption provides beneficial nutrients, including omega-3 fatty acids, it also may contain harmful chemicals such as mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Mercury is associated with neurodevelopmental disorders in infants and children. PCBs, a class of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, can mimic the body’s hormones and may lead to reproductive and developmental disorders.

Turyk aims to reduce harmful exposures from contaminated fish by using targeted interventions to improve environmental health literacy.. She and colleague Susan Buchanan, M.D., lead the NIEHS-funded Fish Intervention Study for Health project, which is part of the Research to Action program. The goal of this study is to promote healthy seafood choices, specifically among Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese individuals in Chicago.

Understanding Diet and Exposure

Community focus groups met to help the research team understand fish consumption behaviors and attitudes.

(Photo courtesy of Mary Turyk)

Turyk and her multidisciplinary research team used the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data to understand dietary trends in fish consumption but realized there was a gap.

“When looking at NHANES data, the Asian community has substantially higher fish consumption and higher documented levels of mercury and PCBs. But the published literature focused on this association was primarily performed on the East and West coasts where the Asian population tend to be more accultured than in Chicago,” said Turyk. “My colleagues and I became interested in studying how fish consumption affects Asian communities’ exposure to pollutants locally.”

Local knowledge from community-based organizations was instrumental to the team and helped them better understand cultural dietary practices among the diverse Asian communities. The research team sought out partners with shared interest in their identified populations. The team built relationships with several community-led centers and programs including the Midwestern Asian Health Association, Hanul Family Alliance, Vietnamese Association of Illinois, and the Chinese Mutual Aid Association.

These partner organizations helped the research team enroll participants from the Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese population to participate in surveys and focus groups.

The focus groups helped Turyk and her team understand common fish consumption, preparation, and purchasing behaviors and refine the community survey. The research team used surveys to ask participants about consumption trends and knowledge about risks and benefits of fish consumption. As a result, they were able to identify risk factors for elevated mercury and PCB intake from fish and to compile a tailored seafood dietary advisory.

Meeting the Community Where They Are

The research team began creating culturally appropriate targeted health messaging based on the focus group data. Through text messages, website resources, and print materials the team provided tailored guidance focused on limiting consumption of fish with higher levels of contaminants and emphasizing fish species with lower levels of contaminants.

The February 2021 panel in the calendars given to the community.

(Photo courtesy of Mary Turyk)

The research team conducted a randomized control trial with reproductive aged women to test the effectiveness of their messaging. The team found their original communication strategy did not meet the needs of the community partners.

“What the community responded to was very different from what had been used in other studies—not only by way of text messaging, but even through our printed materials,” said Turyk. “Feedback from our community partners suggested that a great tool may be a calendar or reusable grocery bags rather than pamphlets and brochures.”

Responding to guidance from their community partners, the research team designed grocery bags with fish advisories and recruited a local artist to design calendars in three different languages that compiled fish advisories, recipes, and pictures. These calendars provide guidance on fish consumption and enable seafood choice to be part of daily meal planning.

Community partners are also engaged in disseminating the study findings through local Asian media markets and interviews, both of which have reached wide audiences and generated community interest.

The trial also utilized reported seafood consumption and mercury level biomarkers, collected via hair sampling, to quantify potential reductions in mercury resulting from health education over a 6-month period. The team is currently in the process of analyzing those samples.

“Our study is wrapping up, but we plan to keep the website active,” said Turyk. “We hope the resources we created for the community continue to be useful and have lasting impact and that more calendars can be printed for next year.”

Exploring Health Effects of Pollutants in Fish

Turyk recognizes that there are multiple pollutants in fish, which may affect human health. Therefore, in another NIEHS-funded research project, Turyk is exploring how chemical mixtures, such as PCBs, mercury, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and perfluoroalkyl substances in fish may contribute to increased incidence of diabetes, underactive thyroid, and high cholesterol.

“Studying exposure to mixtures of chemicals is complex because sometimes mixtures can produce health effects greater than each chemical would alone,” said Turyk. “We need innovative statistical methods to understand how exposure to real-world chemical mixtures contribute to disease.”

As part of the NIEHS Powering Research Through Innovative Methods for Mixtures in Epidemiology (PRIME) Program, Turyk is doing just that. She co-leads a team that is developing advanced statistical approaches to examine the relationship between exposure to harmful chemicals and nutrition that may help protect health.

Related Links

- Check out handy guides to selecting healthy fish, available in four languages, created by Turyk’s team.

- Read more about Turyk’s work to promote healthy fish consumption among Asian communities.

Luz Huntington-Moskos, Ph.D. – Partnering With Youth to Support Environmental Health Literacy in the Next Generation

April 26, 2021

Huntington-Moskos is an assistant professor in the School of Nursing.

(Photo courtesy of Luz Huntington-Moskos)

Luz Huntington-Moskos, Ph.D., believes that youth have the power to positively impact their communities. As director of the Community Engagement Core at the NIEHS-funded University of Louisville’s Center for Integrative Environmental Health Sciences, she is committed to supporting adolescent’s involvement in environmental health efforts. She connects with youth and other community groups to support and encourage the development of environmental health literacy throughout western Kentucky.

Center research addresses lifestyle behaviors and their connection to contaminant exposures in western Kentucky, where agricultural and industrial sectors often exist side by side, affecting community partners throughout the area. To bridge varying land-use perspectives among stakeholders, Huntington-Moskos focuses on community members’ interests, personal experiences, and the environmental health priorities they identify.

By tailoring communication methods to specific communities and highlighting the relevance of available center resources to community environmental health, she aims to improve environmental health literacy across western Kentucky and the Louisville metropolitan area.

“My goal is to have a good foundation of environmental health literacy in all communities – rural to urban, older adults to adolescents – to help everyone incorporate informed perspectives in their daily life choices,” explained Huntington-Moskos. “I want to support people to make healthy choices while shopping, working out, and eating, not only for their individual health, but for healthier communities.”

Creating Healthy Communities From the Ground Up

Sharing environmental health ideas with the next generation has always been a central goal for Huntington-Moskos. Sowing knowledge that cultivates fresh ideas is the defining theme of her work whether she is teaching new nurses, developing adolescent advisory boards for research projects, or ensuring that the Center’s work with community partners incorporates youth perspectives.

“Adolescents are an untapped resource with so much potential,” said Huntington-Moskos. “As digital natives, they are so creative and see the world differently than previous generations.”

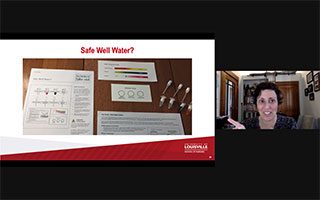

Huntington-Moskos uses Science Take-Out Kits to engage with high school students in virtual presentations discussing environmental health topics such as water quality.

(Photo courtesy of Luz Huntington-Moskos)

Since beginning her tenure as director of the CEC in July 2020, Huntington-Moskos quickly focused on virtual platforms such as Zoom or Microsoft Teams to engage young community members. She runs interactive, hands-on activities to maintain engagement with participants. With visual demonstrations of Science Take-Out Kits provided by Dina Markowitz, Ph.D., a member of the CEC at the NIEHS-funded University of Rochester Environmental Health Sciences Center, Huntington-Moskos leads high school students through these virtual activities, poses health-related questions, and asks youth for their input regarding various environmental exposures found in their home communities. These kits have allowed Huntington-Moskos to continue sharing knowledge and gathering feedback from youth on their priorities.

“You have to think outside the box and be flexible with the tools available to you,” she said. “These kits have been effective in meeting people where they are and simulating what would normally be in-person experiences.”

Along with high schoolers, the CEC also targets early-career healthcare providers who are still in training. Huntington-Moskos believes early-career healthcare providers can greatly benefit from incorporating environmental health education in clinic visits when speaking with patients. A focus on sharing environmental health knowledge and skills with early-career health professionals increases the potential for knowledge transfer to their patients, the communities they serve, and can even benefit the health professional’s own family.

“We strive to work with a whole spectrum of people,” explained Huntington-Moskos. “There is a lot of overlap working with both healthcare and high school groups and this helps build momentum for our center.”

She says keeping early-career and young people at the core of the CEC’s endeavors creates positive impacts on communities which will grow health benefits into the future.

Merging Disciplines to Make Science Accessible

As director of the CEC, Huntington-Moskos’ goal is to make science universally available and useable.

“I worry that sometimes people feel like science is for this elite, separate group when really science is for everyone,” she said.

In partnering with laboratory scientists, Huntington-Moskos combines her nursing background with their subject matter expertise to translate technical scientific concepts and jargon into more understandable messages. Huntington-Moskos knows part of the job of nursing is effectively communicating with patients and linking research results to disease outcomes.

“As partners, laboratory scientists and nurses can leverage strengths from our disciplines to help communicate in different ways,” she said. “This helps us talk with our community partners, youth groups, and the broader public about science in effective ways and make sure the essential information is easy to consume.”

Effective communication and youth engagement are key tenets of the work Huntington-Moskos hopes to accomplish with her Center colleagues and community partners.

“As I move forward in my own research or in my role as director, I want to make sure I’m always keeping community engagement and adolescent involvement at the center of everything,” she said.

Related Links

- Learn more about the Science Take-Out Kits Huntington-Moskos uses during her virtual youth engagement presentations.

- Read Huntington-Moskos’ recent publication Authentic Youth Engagement in Environmental Health Research and Advocacy in the International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health.

- Under Huntington-Moskos’ leadership, the CEC is working to integrate the NIEHS Translational Research Framework throughout the center.

Natalie Sampson, Ph.D. – Building Capacity in Community Science to Address Environmental Inequalities

April 7, 2021

Sampson is also the Chair-Elect of the American Public Health Association’s Environmental Section which strives to inspire systemic change through science-based advocacy and programs.

(Photo courtesy of EHRA)

Natalie Sampson, Ph.D., is an environmental and public health researcher at the University of Michigan-Dearborn. Her research covers a variety of social and environmental determinants of health. Sampson partners with communities and the local government, primarily in Southeast Michigan, to plan and evaluate program, policy, and land-use interventions to improve health equity.

While working on her bachelor’s degree at the University of Michigan, Sampson joined a grassroots-led organizing effort to understand how truck traffic on the Ambassador Bridge and lack of environmental protections at one of the largest border crossings in the U.S. affected the surrounding community.

“The Ambassador Bridge really helped me understand how land use and infrastructure, whether it’s transportation, waste management, or stormwater infrastructure, affect public health,” said Sampson. “Many of those decisions are rooted in current and historic racist policies. They get made outside of the public health sector without community input and have huge implications for environmental health and environmental justice.”

Sampson now works at the intersection of community-based research, environmental health, and land use and health.

“My work really aims to rethink environmental decision-making, from problems with the underlying risk assessment frameworks, to the lack of plain language used to communicate risks, and the inequitable power structures that drive decisions,” said Sampson.

Making Research Meaningful to All Stakeholders

Today, Sampson co-leads the Community Engagement Core (CEC) at the Michigan Center on Lifestage Environmental Exposures and Disease (M-LEEaD), an NIEHS-funded Environmental Health Sciences Core Center. A key role of the CEC is to facilitate multi-directional interaction between center researchers, policy makers, and communities.

In 2016, she partnered with the Southwest Detroit Community Benefits Coalition to design and launch an extensive survey to understand community concerns and priorities related to a new international bridge under construction. Residents near the construction site have been working for decades to address the effects of multiple pollutant sources in the area including transportation and industrial activity.

“Residents, researchers, and students collaborated to design the survey questionnaire and methods, conduct the household surveys, and interpret the findings,” said Sampson. “The survey’s results provided a springboard for one of the coalition’s subsequent requests to local and state leaders to conduct a health impact assessment.”

The health impact assessment was conducted by the Community Benefits Coalition with the M-LEEaD CEC and NIEHS grantee Angela Reyes. Reyes is the executive director of the Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation and a member of the M-LEEaD CEC Stakeholder Advisory Board. In 2020, the team published findings and recommendations from the first phase of the assessment. The case study also provided lessons for community, academic, and government partners conducting health impact assessments, especially during building and operation of major infrastructure. For example, strengthening existing relationships to form solid partnership between academic, government, and community members and developing principles and processes for translating research findings into actionable community-identified solutions.

Building Knowledge Across Generations

Sampson is also a co-founder of the Environmental Health Research-to-Action Youth Academy, which brings together community and academic partners to build capacity across generations in community science and policy advocacy to address environmental racism.

Youth ages 16 to 18 apply to participate in the two weeks of intensive active learning.

(Photo courtesy of EHRA)

According to Sampson, the youth academy’s vision was naturally identified by members from several community, academic, health care, government, and faith-based organizations who were concerned about air quality issues.

“Many of us had already been working with youth or college students and there was a lot of excitement about building something intergenerational,” said Sampson.

Zeina Reda, an alum of the 2018 Academy and now undergraduate student at the University of Michigan, recently joined the organization as youth coordinator. She helps ensure youth voices are centered, and she steers the curriculum of the academy, which involves bus tours of local air pollution sources, environmental risk and asset mapping, and engagement in policy education trainings.

“A community that understands the environmental dangers it faces will lead with a more powerful voice and stronger position on promoting environmental justice,” said Reda. “With this curriculum, we are able to empower the next generation to advocate for their basic rights to clean air and equitable living conditions.”

Advancing the Field

The work the youth academy and the CEC are doing has come a long way, but Sampson says the job is far from done. She looks forward to expanding youth-oriented programming, building academic and government capacity to support community-led science, and breaking down the boundaries and silos between research and policy to inspire systemic change.

“I think the field of environmental health, our agencies, and our institutions have a long way to go, and I'm committed to doing that work,” stated Sampson.

Mindy Richlen, Ph.D. – Developing Innovative Community Engagement on Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs)

March 22, 2021

Richlen is assistant director of the U.S. National Office for Harmful Algal Blooms at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. “A lot of the work I'm doing now is leveraging tremendous opportunities that I’ve had through a lot of these research programs. It’s gratifying to see these programs coming together in a way that is much more impactful,” said Richlen.

(Photo courtesy of WHOI)

Mindy Richlen, Ph.D., grew up in southern Idaho, far from any ocean. An inspiring elementary school teacher sparked a lifelong interest in biology, which led her to pursue a Ph.D. in biology at Boston University. While there, Richlen’s advisor introduced her to harmful algal blooms (HABs), which occur when certain algae species grow rapidly and produce potent toxins.

Richlen’s graduate research focused on the HAB phenomenon known as Ciguatera Poisoning. It is one of several HAB-related illnesses and is caused by eating coral reef fish or invertebrates that are contaminated with ciguatoxin when they consume harmful algae. When people consume seafood carrying these toxins, they can experience gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, or neurologic symptoms.

“A lot of people have never heard of ciguatera, but it has the greatest public health and economic impacts of all the HAB-related illnesses,” said Richlen.

Today, Richlen remains engaged in research on ciguatera as a co-investigator at the Greater Caribbean Center for Ciguatera Research (GCCCR), funded jointly by NIEHS and the National Science Foundation (NSF). Her research, which now includes other types of HABs, has taken her from the tropics to the Arctic to study the complex factors involved in HAB formation and their effects on human health.

She is also involved in improving coordination and collaboration within the HAB research and management community. Richlen leads the NIEHS and NSF-funded Woods Hole Center for Oceans and Human Health (WHCOHH) Community Engagement Core (CEC). Both WHCOHH and GCCCR employ interdisciplinary approaches to understanding the causes and effects of HABs.

“All HABs are different. They involve different species, have different biogeography, and different physiologies. Our research programs are certainly strengthened by an interdisciplinary approach.”

Using Real World Data on HABs in the Classroom

When the concentration of harmful algae increases and forms a bloom that is dangerous to human health, beaches may be closed, or an advisory warning of the risks may be posted. Fisheries might close and issue recalls, minimizing harm to health. These closures, though temporary, can have significant economic and social implications. Since many communities are affected by the health, social, and economic impacts of HABs, community engagement is a key part of Richlen’s work.

“I became involved in community engagement through my work with the U.S. National Office for Harmful Algal Blooms,” Richlen said. “Our main goals are to improve information sharing, coordination, and communication within the HAB research and management community as well as with the public.”

Richlen seeks to expand community engagement through the WHCOHH CEC. This group participates in the HAB network of researchers and managers to discuss challenges and solutions and has a strong emphasis on classroom education and building environmental health literacy for the public.

In collaboration with WHCOHH co-investigators, the CEC is developing an open source, online data portal for tracking HABs of different species over time called the WHOI HAB Hub, which will integrate different data sources and provide real time data. The tool will be useful for HAB researchers, managers, the shellfish industry, and the public.

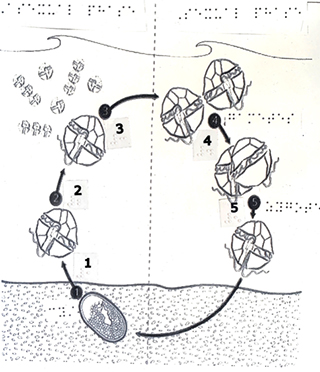

Richlen’s engagement with the community extends to the classroom, where she first became inspired to pursue biology. In collaboration with Carla Curran, Ph.D. at Savannah State University, Richlen developed interdisciplinary educational activities about HABs and paralytic shellfish poisoning for middle school students that can be adapted for high school.

“We use HABs to illustrate a number of different concepts, including biology and ecology, marine science, math, and data analysis,” said Richlen. “We also include opportunities for students to work with data produced by center research.”

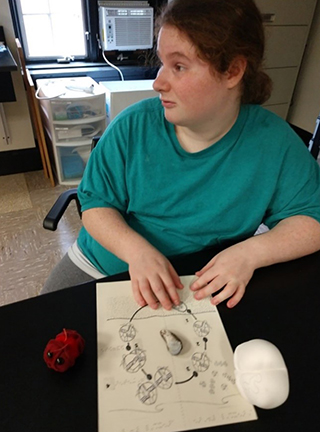

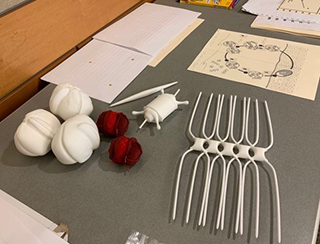

The lesson plans use tactile teaching aids, including raised line drawings with Braille captions and three-dimensional printed models of HAB species, to engage with visually impaired students. The activity focused on paralytic shellfish poisoning was introduced to several classrooms in Florida and Massachusetts and presented at the National Marine Educators Association Conference in 2019 to solicit additional feedback from teachers.

“We’ve found this approach has helped students be very engaged and interested in learning about HABs,” Richlen noted. “Teachers also appreciate that their students had the opportunity to work with real data, so this has been a really successful collaboration.”

Next Steps and Future Directions

Building on the success in Florida classrooms, Richlen and Curran will introduce another set of activities for students in the New England region focused on algae that cause amnesic shellfish poisoning.

“Amnesic shellfish poisoning is a fairly recent problem in the Gulf of Maine,” she said. “The new classroom activities will focus on analyzing temporal changes and algae community structure. All of these data were collected by Dr. Kate Hubbard a co-investigator on one of our projects.”

Moving forward, Richlen hopes to collaborate with the other three centers involved in the CEC and to bridge connections between the WHCOHH and the public health and medical communities.

“Expanding education on HABs for clinicians is critical to improving the recognition and reporting of HAB-related illnesses,” she said. “This information will allow for better tracking of public health impacts at the national level.”

Related Links

- Learn more about the Woods Hole Center for Oceans and Human Health and the Greater Caribbean Center for Ciguatera Research.

- Read more about the classroom activities that include adaptations for visually impaired students.

- View the One Health Harmful Algal Bloom System for reporting HAB surveillance data related to human, animal, and environmental impacts.

- Visit the Northeast HAB webpage to learn more about HABs in New England and access real-time data through the WHOI HAB Hub data portal.

- Visit the U.S. National Office for Harmful Algal Blooms for information about HABs and their distribution and impacts in the U.S., as well as national and international research programs.

Angela Reyes – Addressing Air Pollution Effects With Multidisciplinary Matchups

February 23, 2021

Angela Reyes received her master’s in public health degree from the University of Michigan. “I started working with NIEHS -funded grantees at the University of Michigan prior to pursuing my M.P.H., and it is because of my relationship with them that I was able to go to graduate school,” she said.

(Photo courtesy of Angela Reyes)

Angela Reyes strives to create healthier communities and address issues of racial inequity and health disparities in Southwest Detroit. She has devoted her career to addressing environmental justice issues by fostering long-term relationships with local community groups, academic researchers, and decision makers.

“Growing up, I witnessed first-hand how people in my community are disproportionately at risk for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, which are linked to air pollution exposure,” she said. “When you are around so much pollution all the time, it is hard to ignore the impact of the environment on our health.”

Today, Reyes is the executive director of the Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation (DHDC), a community-based organization she founded over 20 years ago. DHDC is committed to providing opportunities for self-empowerment and education for disadvantaged youth and families. By doing so, they hope to build a healthy and safe community, particularly for Hispanic populations in southwest Detroit.

Improving Lives by Collaborating With Academic Institutions

For over 25 years, Reyes has worked closely with NIEHS grantees at the Michigan Center on Lifestage Environmental Exposures and Disease (M-LEEaD) at the University of Michigan, where she is a member of the Stakeholder Advisory Board. The board’s purpose is to strengthen dialogue between center researchers and community leaders to ensure effective dissemination and implementation of research findings. Reyes is also an active member of the Community Engagement Core at M-LEEaD.

According to Reyes, strong partnerships between community organizations and researchers are necessary to facilitate the translation of scientific findings into policies that address the systemic public health issues that Detroit residents face.

“Working alongside the University of Michigan gave the DHDC the credibility and tools to prove exactly how serious the air quality problem is in our community and negotiate several community benefits with the city,” she noted. “We would not have been able to do that without science to back our case.”

Community Action to Promote Healthy Environments

Today, DHDC, alongside M-LEEaD, is helping address the air quality problem through their participation in the Community Action to Promote Healthy Environments, a partnership among community-based organizations and academic institutions.

The groups have collaborated on a variety of community-based participatory research projects aimed at improving health and the quality of life in communities disproportionately affected by air pollution.

During its first stage, this program documented air pollutant levels, sources, and distribution. Additionally, they quantified health impacts and inequities to develop a Public Health Action Plan to reduce exposure and improve human health. The plan detailed 25 actionable strategies based on science and community priorities, such as incorporating vegetative buffers, installing air filters, and improving infrastructure to allow for alternative transit forms like biking.

As the program embarks on a new funding cycle, the team is working toward developing a network of air monitors across Detroit. They plan on creating a web-based platform for community members to monitor and take actions to improve air quality. Additionally, Reyes is looking forward to working with schools near air pollution sources, such as chemical plants, to improve infrastructure and install air filters.

Southwest Detroit Community Benefits Coalition

Reyes also serves in an advisory capacity for the Southwest Detroit Community Benefits Coalition. There is a new six-lane bridge being built in the immediate vicinity of a steel mill, an energy plant, a wastewater treatment plant, an oil refinery, and other industrial sites that increase air pollution.

The cumulative impact from industrial and transportation-related air pollution sources will further negatively impact nearby communities. Reyes, along with researchers at the University of Michigan and the coalition, are working to ensure these communities receive appropriate protections and benefits to protect their quality of life. They have been able to negotiate with the city of Detroit and the state of Michigan to allocate funding for air monitoring equipment over 10 years, home repairs to improve indoor air quality, and housing swaps for people near the bridge.

Additionally, funds will be allocated for a health impact assessment to take place in three phases: before construction, during construction, and during operation of the bridge.

“Getting support for the assessment was a major milestone. This will allow us to document existing air quality and health conditions and track changes over time, as well as identify strategies to reduce health impacts,” she noted.

The team recently documented select findings and recommendations from the first phase of the health impact assessment. According to Reyes, the most interesting outcome is that the assessment allowed them to quantify the number of lives and how much money would be saved by addressing the air pollution issues.

Training Future Environmental Justice Advocates

Reyes works closely with a youth group that is involved in policy advocacy and creating innovative solutions to address air pollution. The DHDC is dedicated to creating a safe space for youth to voice their opinions and become involved in addressing environmental justice issues within their community.

“By exposing young people to science and advocacy early on, we are helping them develop leadership and critical thinking skills,” she said. “For example, our kids are developing an app to spread the word about air quality issues by posting real-time information.”

Reyes is also involved in offering education and leadership development opportunities for parents in the community to increase their capacity to engage in community organizing, mobilization, and advocacy. The DHDC frequently leads tours in both Spanish and English through Southwest Detroit, where some of the largest refineries and chemical plants surround neighborhoods and spew toxic substances into the air.

“One of the biggest determinants of health is education,” Reyes noted. “When parents see how bad the air pollution problem is, they immediately want to get involved to make changes because it impacts their children.” By educating individuals on health concerns and implications surrounding environmental pollution, Reyes strives to build capacity for effective community action and greater public participation.

Montgomery Proffit – Making an Impact Through Employment Opportunities

January 26, 2021

“I appreciate the resources that NIEHS has provided for OAI to make an impact in people’s lives,” said Proffit. “We are able to help people provide for their families and to become stewards of their communities.”

(Photo courtesy of Montgomery Proffit)

Montgomery Proffit is passionate about helping people obtain safe and sustainable employment.

A native of Chicago, Proffit has witnessed the economic barriers and health disparities that many communities face in the area. After working a few years in law enforcement, he joined Opportunity Advancement Innovation in Workforce Development (OAI, Inc.) in 2001 as a case manager for its Welfare to Work program. He provided employment assistance and support services for low-income and underserved populations.

Today, Proffit is director of the NIEHS-funded OAI Environmental Career Worker Training Program (ECWTP) Consortium in Chicago. He helps individuals from disadvantaged communities obtain the necessary skills for work in environmental careers, such as construction and hazardous waste cleanup.

Continuing the Legacy, Serving Others

OAI is one of many nonprofit organizations funded by the NIEHS Worker Training Program (WTP). Established in 1995 by founder and former principal investigator Tipawan Reed, OAI has a mission to provide skills training that leads to safe, meaningful employment while helping companies and communities to thrive.

Proffit said OAI’s legacy is built upon the diligent efforts of leaders like Reed and Sheila Davidson Pressley, Dr.P.H., former manager and senior advisory board member at OAI, who instilled a culture of compassion and serving others. The legacy now continues with Executive Director Mollie Dowling; Salvatore Cali, who is principal investigator for WTP activities; Proffit; and others.

Proffit (far right) poses with colleagues for a group photo following an ECWTP graduation ceremony.

(Photo courtesy of OAI, Inc.)

“The people we serve come in with many social and economic barriers,” Proffit said. “Some have never worked, are recovering from addiction, or have spent most of their adult life incarcerated. We provide them with support and resources to guide them through these barriers.”

The OAI ECWTP uses an innovative try-out program for to recruit and select individuals for enrollment. The try-out program has been a hallmark of OAI’s ECWTP and has helped increase student retention over the years.

The OAI ECWTP falls under the umbrella of WTP activities but is focused on providing life skills and pre-employment training for underrepresented and unemployed individuals. The life skills component includes courses focused on professional development, financial empowerment, and other topics. The health and safety component includes courses mandated by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration with a focus on hazardous waste, operations, and emergency response and others tailored to participants’ career of interest.

After graduation, participants obtain employment in industries like electrical services, construction, and solar and renewable energy. In 2019 alone, the OAI ECWTP trained 85 people, and 80% of these individuals were placed in jobs.

Forming Intentional Partnerships

Successes of the OAI ECWTP Consortium are largely due to great partnerships formed over the years. The consortium’s anchor program is based in Chicago, but partners in other locations including Dallas; Kansas City, Kansas and Missouri; and Indianapolis, help extend the consortium’s reach and impact.

“I am very deliberate about networking and learning more about different agencies and organizations,” he said. “The key to finding a good match is measuring their mission and principles against the principles of the OAI ECWTP.”

As they embark on a new funding cycle through WTP, Proffit and his team look forward to continuing efforts with partners like CitySquare in Dallas and NuStart Career Builders in Kansas City. The team is also excited to begin work with new partners, such as Amplify Chicago and RecycleForce in Indianapolis.

Amplify Chicago helps young people in the justice system obtain a professional career path. RecycleForce offers training in e-waste and recycling for individuals who are re-entering the workforce. Proffit noted that both organizations hold great potential due to high success rates within their target populations.

Adaptability During Disasters, COVID-19

In 2015, the OAI ECWTP in Chicago began using a blended learning approach, where training courses are delivered through a combination of classroom and online methods. Proffit noted that this foresight was critical, as the team was able to quickly adapt in-person courses to a virtual learning environment in a few short weeks at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

To account for health and safety concerns, the team is also making other adjustments for training space and recruitment. Proffit said while COVID-19 brought many challenges, it has taught the team valuable lessons for the future.

“The method of delivery is important for the populations that we serve,” he noted. “We must have interesting and interactive online content to engage our participants. We are not just training to train, but we want to be effective and train with purpose. That is how we will continue to make an impact.”

Sharing Lessons, Preparing New Leaders

Proffit said mentorship and lessons from leaders like Rosie Carter, Jack Huenefeld, and Patrick Brown, cultivated his career path in worker health and safety. When asked what advice he would offer to new leaders and organizations funded by WTP, Proffit offered a few tips.

“Learn to be at the right place at the right time and be willing to try new things,” he said. “Don’t be afraid to fail because you will learn from your mistakes.”

He also offered tips for recruitment of training participants.

“Word of mouth sells a program, so be methodical and offer individuals an experience,” he continued. “Under promise and over-deliver – promise them the sky but give them the moon and the stars.”

Proffit also recalled that, as a child, his mother reminded him to be grateful and help those who are less fortunate. This message has been a part of his life motto ever since – to reach out and make an impact.